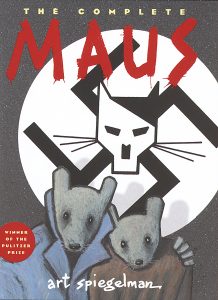

The epigraph for “Maus,” Art Spiegelman’s brilliantly conceived chronicle of the Holocaust, or Shoah, quotes Adolf Hitler: “The Jews are undoubtedly a race, but they are not human.” In a sly twist on that slur, Spiegelman turned Jews into mice and Germans into cats in his powerful personal recounting of an incomprehensible tragedy seen through the life of one man, his father.

Unfortunately, eighth-grade students in McMinn County, Tennessee, will no longer get to read Spiegelman’s graphic novel in class because of the judgment of the local school board that a pen-and-ink drawing of a naked mouse and a few bad words made history unsuitable for modern children.

The timing of the school board’s decision to remove the book from the school curriculum was inopportune at best, occurring not long before Malik Faisal Akram held four people hostage in a Texas synagogue. It happened weeks before Holocaust Remembrance Day, which Pope Francis marked by saying that the Nazis’ “unspeakable cruelty must never be repeated,” and “must not be forgotten.”

The school board’s decision came in the wake of a disturbing increase in antisemitic acts, including the Tree of Life Synagogue massacre in Pittsburgh and the white nationalist tiki-torchers marching in Charlottesville while chanting, “Jews will not replace us.”

Not just eighth-graders, but we all should have the horror of the Holocaust burned into our memory. This is not just a memory for the Jews who survived it, nor should it be a memory for Jews alone to preserve. It must be a cultural memory for all of us, a grim warning sign of the extent to which hatred and fear can corrupt an entire culture. How the ancient bigotry of antisemitism infected not only all levels of German society but even those ordinary citizens from France to Poland who became passive or active collaborators in a systematic effort to extinguish a people from this earth.

Unfortunately, instead of a collective social memory warning us of evil’s heart of darkness, the Holocaust has become a meme, a slogan for exaggerated analogies that at the same time drain it of all significance and weight.

One politician recently invoked the Holocaust, comparing COVID vaccination mandates to passes that people were required to carry under the Nazi regime. More than a few compared mandatory mask-wearing to the yellow Stars of David that the Nazis forced Jews to wear.

Despite the fact that 15% of U.S. adults have not yet received a single COVID vaccine, anti-vaccine campaigner Robert Kennedy Jr. claimed at a recent rally in Washington, D.C., that anti-vaxxers have it worse than Anne Frank because “even in Hitler’s Germany, you could cross the Alps to Switzerland. You could hide in an attic like Anne Frank did.” It was an analogy so inept and historically false (she died in Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, after all) that it leaves one stunned at its insensitivity.

Anthony Fauci, the doctor who has battled diseases from AIDS to COVID, saving thousands if not hundreds of thousands of lives, has been compared by certain critics to the Nazi doctor Josef Mengele who sadistically tortured and killed Jews in his “experiments.”

In a democratic society, one may object to mandates and masks and doctors advocating for public health, but to compare efforts to stop a global pandemic to the killing of 6 million Jews is a historical obscenity. The trivialization of these historical events coincides with a resurgence of antisemitic propaganda from both the far right and the far left less than a century after the Holocaust: Talk of plots and race wars and conspiracies of global elites use many of the same antisemitic tropes of the Nazis. When Malik Akram held four Jews hostage in that Texas synagogue, he did so reportedly because he believed Jews controlled the United States and thus had the power to arrange the release of an ISIS prisoner.

Why all this ignorance and hatred now?

Dara Horn, in her collection of essays titled “People Love Dead Jews: Reports from a Haunted Present” (W.W. Norton & Company, $25.95), suggests the anomaly is not the antisemitism, but the few decades when it was considered unacceptable. “In other words,” she wrote, “hating Jews was normal. And historically speaking, the decades in which my parents and I had grown up simply hadn’t been normal. Now, normal was coming back.”

God forbid this should happen, but to make such hate and ignorance unacceptable, we must remember. Memory is what has preserved Judaism all these millennia. “Maus” is itself an act of memory, a refusal to allow one man’s experience to disappear. Art Spiegelman’s father is remembering for the sake of all of us.

The preservation of this memory is ultimately a gift for both Jew and non-Jew. It is also a warning. To forget, to trivialize, to deny is to grant breath to the nightmare once more.