Editor’s note: The following column first appeared in The Tidings in July 2015. It has been updated by the author in light of Msgr. Richey’s death last month.

When I came into the Church 26 years ago, I wasn’t friends with a single practicing Catholic, much less a Catholic who might understand that I’d been led to Christ through my recovery from alcoholism.

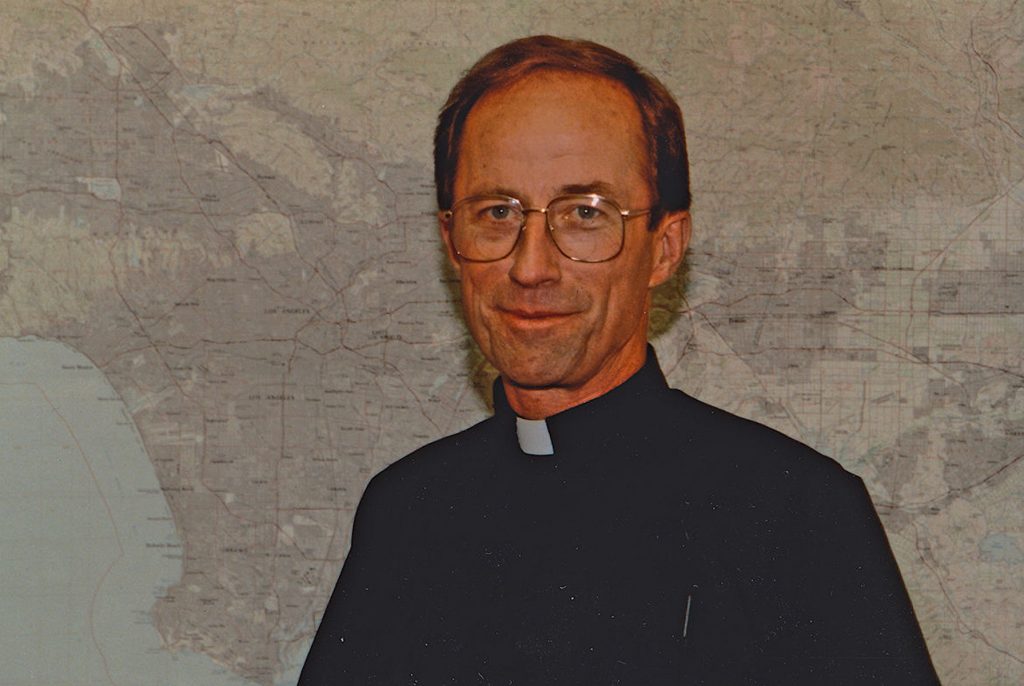

Then I met Msgr. Thomas Terrence Richey, known by recovering alcoholics and addicts throughout the archdiocese and beyond as Father Terry.

Anyone who knew Father Terry knew that he was the king of the one-liner.

“Drinking never made me happy — but it made me feel like I was going to be happy in 15 minutes.”

“The good news is God loves you. The bad news is he loves everyone else, too.”

I once asked him how I’d know if I was making spiritual progress. He thought for a minute. “If crazy people aren’t afraid to come up and talk to you,” he replied, “that’s a pretty good sign.”

A native of Hawthorne, Father Terry entered the seminary at 14, served as director of Alcohol/Substance Abuse Ministry for the archdiocese for many years, and throughout the decades conducted interventions, led retreats nationwide, and was a friend to many at first glance “very unpromising” people.

For decades he directed alcoholics and addicts to Alcoholics Anonymous (AA). He’s also observed what happens to them once they get there.

“To be a drunk and get sober,” he pointed out, “is one of the ultimate death-and-resurrection experiences. When Christ said, ‘Blessed are the poor in spirit,’ some of the people he must surely have been thinking about were alcoholics and addicts. It’s a wonderful gift for a person to see, left to his or her own devices, the depths to which we’re capable of sinking. Sometimes I don’t know how people come to a relationship with Christ without hitting bottom with some kind of addictive, obsessive behavior.”

I’d lived my whole life in fear of judgment. The first time I heard Father Terry, he talked about how when we get sober, or we come into the Church, we are in fact judged. We’re judged welcome.

“We welcome you and we also recognize you as a child of God with the dignity of any other person on earth. We’re judging you to be a person of high standards, a person who will not be satisfied with acting from a heart that’s anything less than entirely free. And we have some principles of loving, honest, responsible behavior that we suggest you follow. You’ll stay welcome even if you don’t follow them, but — here’s the thing: you won’t care. You won’t care that you’re welcome; you’ll miss out on all the wonder, the love, the growth.”

Many of us are looking to be transformed in a certain way. It helped to hear that resurrection never looks anything like we think it’s going to.

“Some of us have a deeply misguided desire to be saved through excellence,” Father Terry would note with a chuckle. “We want to be spontaneous yet profound, highly intelligent yet down-to-earth, well-balanced yet passionate, dignified but self-deprecating. We want to be physically fit, good-looking, calm in the face of tragedy, suave in the face of heartbreak, and to have really, really good skin. Through the incarnational mystery of being broken open by fellow alcoholics and addicts, we forget about all that. We become what we really wanted to be all along: we become human. We realize the real point of sobriety is to get in good enough shape to help another alcoholic.”

Still, old habits die hard. Who would I be, I wondered, without my perfectionism? My need to control? My accusatory self-talk?

Father Terry would respond, “Implicit in all self-justification is accusation: One of the names for Satan in Catholic theology, in fact, is The Accuser. That’s not God talking to us; that’s us talking to ourselves. There’s no accusation in authentic spirituality — only invitation.”

Two things happen when someone comes into AA, he maintained. The first is that there’s a kind of unspoken joy in the people who welcome and greet you. “Right away they trust that you have it in you to respond to the invitation of sobriety. You don’t get the bum’s rush. No one swarms you. There’s a spiritual maturity.”

“It’s not in the mind of anyone who walks through the doors of AA,” he added, “ ‘I wish someone would see my goodness, my inner essence.’ That thought isn’t conscious. But we all need so much to be welcomed and trusted and honored as free children of God. And when that happens, some real change can occur.”

The second thing that happens is the spontaneous urge to carry the message and treat other people the way you’ve been treated.

“We have an inborn need to love. And in AA people are drawn to, find themselves, identifying with, the other. That ‘Yeah!’ to other people’s brokenness, escapades, sense of humor, remorse, and willingness to make things right is a profound spiritual experience. People feel joy that someone else is coming alive; they’re triggered into identification. Those who stay sober in AA tend to have a little bounce to their step.”

Father Terry would go on to become a monsignor. I was able to visit him over Thanksgiving at the memory care facility where he spent the last year or so of his life. He died in December, on the winter solstice.

He formed me — and thousands others — deeply as a recovering alcoholic, as a follower of Christ, and as a human being.

And he always, always made me laugh. One spiritual director he used for years was Mark Kennedy, himself a recovering alcoholic. “Mark used to say: ‘There’s only one unforgivable sin. And that’s to avoid God until you’re in good enough shape to fool him.’ ”

The funeral Mass for Father Terry will be held Tuesday, Jan. 10, at St. Basil Church, 3611 Wilshire Blvd., Los Angeles, at 11 a.m. Reception to follow in McIntyre Hall.