The Book of Ecclesiastes tells us that to everything in life there is a season, and an appointed time for every human experience. Our ancestors understood this — they lived the rhythms of life and respected them, their livelihoods tied to the harvests or the tides. They lived patiently attuned to the muffled cadences of their hearts, both the glad tempos and the dirges.

Today it is harder for us to accept the true fullness of human experience, the wide breadth of the seasons of life. We live in rigidly controlled environments, our thermostats set to 73 degrees in summer and winter, our pantries full of the same food the year round. We think we can do the same to our hearts, living narrowly only the experiences we crave, like love’s embrace or at the very least the steady hum of a cheerful, active life. The gloomy seasons we reject as unhealthy or morbid, and we seek the therapist’s couch when a swamping tide of loss or grief doesn’t recede at once.

The experience we fear the most is that of death, with its awful finality and hideous separation. And yet death is embedded in life, here to stay. With all our scientific progress we have not been able to extend our lifespan at all, let alone begin to see a way to achieve the pipedreams of billionaires who have poured their capital into “solving” death.

What we have been able to do is to mute death — compartmentalize it, box it in, marginalize it, remove it from our sight — as we’ve done with many of our cemeteries and funeral homes. Our old people die in hospices, with trained assistants to sedate them on their way, and are rushed to the crematorium when their souls have barely fled. Ashes are scattered in bodies of water, while wakes and funeral rites have been replaced by “celebrations of life.” We are encouraged to celebrate immediately, because grief hurts and what hurts has no business interrupting the cheerful tempo of our modern lives.

My dear father died a month ago. He was 86 and had been diagnosed with the terrible, terminal illness of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) more than two years ago. And yet, I was completely unprepared for his going away from us.

His death had all the hallmarks of a good death: he died in a state of grace, his soul and mind well prepared, nobly accepting the slow crucifixion that God chose for him as his purifying end. He died at home, with my mother, his wife of 56 years, yearning tenderly over him until his last wracked breath. Children and grandchildren surrounded him on his deathbed, suffering but unwilling to miss a last glance from his eyes. It was “normal,” it was “natural,” it was “to be expected,” and it was “a welcome relief.”

Clearly there is nothing for me to complain about. But I am still grieving, and it’s made me reflect on the wisdom of Ecclesiastes: There is, in fact, “a time to mourn,” and I’ve learned there is a blessedness in that time that we do wrong to reject.

The one who has lost enters a different dimension, as though separated by a veil from the unaffected around her. She has come face-to-face with the calamity of death and its incomprehensible transformation of the person she loves.

Where there were eyes with eager welcome there are now glassy orbs that convey nothing. Where there was warm skin to pat and kiss there is something else, yellow and leathery, that repels the touch. Where there were words of affection, forgiveness, and self-sacrificial love, there is silence. She yearns for one moment more with him, a few seconds even, to see his tender smile, which he kept up no matter how cruel the torment of his paralyzed body. But that moment is not to be, and knowing that, she grieves.

Grief is part of true love. When we mourn, observing all the age-old traditions that accompany bereavement, we live rightly through one of Ecclesiastes’ “appointed times.” It’s true that it hurts to carry the leaden weight that bows our shoulders. But when we wear the black that reflects our sadness, kneel in prayer at the coffin, and cry at hearing the Ave Maria in Mass as a great lament, we do what our hurting human hearts need to do: declare to the skies the enormity of our loss.

The extended time of our mourning, the months or years, is also a spiritually necessary time. During that stage, our minds become directed to eternal things, our souls softened for the consolation of the only One who can console. Our hopes go from meagerly material to highly ambitious: we dare to think of things like joyful reunions in heaven and an eternity of happiness.

We have presence of God. We make time for prayer. We discover God is using our period of sorrow to draw us into the pure air of his company. These are graces easily missed when we set our emotional thermostats at the most comfortable temperature and reject the long chill of bereavement.

While the materialist may dismiss mourning as sentimentalism that interferes with an active, achieving life, the Christian today can fall into the same mistake, but for other reasons.

“Don’t be sad, you have an advocate in heaven now,” and “We believe in the resurrection, so there is nothing to cry about. You will be together soon in only a little while.” There is theological truth to these words of comfort, of course. But no Christian should make the error of disdaining mourning and going straight to “celebration.”

Jesus didn’t.

When the Divine Life on earth learned that Lazarus had died, he wept. Think of the enormity of that: The very same person who knew that he would raise Lazarus up again in just a few minutes, and the very same Creator who had planned from the beginning of time to conquer death itself, cried at learning of the passing of his friend. We are meant to imitate Jesus in everything. Should we turn away from grief the way we turn away from his example of forgiveness toward his tormentors?

Why does Jesus weep? Great doctors of the Church have tried to answer that question. St. John Henry Newman, in one of his sermons, mused that it was more than sympathy for Mary and Martha. It was witnessing the victory of death, the greatest of the great miseries of the world — which filled Our Lord’s heart with pity. At the grave of Lazarus, he felt fully the “contrast between Adam, in the day in which he was created, innocent and immortal, and man as the devil had made him, full of the poison of sin and the breath of the grave.”

If this sorrowful contrast, between what God had wrought and sin had corrupted, could bring Our Lord to tears, are we to resist grieving the death of a loved one? We who were made to walk eternally with God are instead destined for the grave, condemned to say farewell to those who seemed indispensable to our earthly happiness.

Of course, Our Lord conquered death through his passion and resurrection, and Christian faith and hope are waiting to relieve our grief in due course. There will come a time, I know, when thinking of my father’s tenderness will bring me smiles, not tears. When I picture his face, it won’t be turned eagerly toward me as I enter his room, but instead gazing happily at the face of God. The time to weep will be over and the time to dance will come, but not until I have allowed the rhythm and cadence of grief to play itself out in my heart.

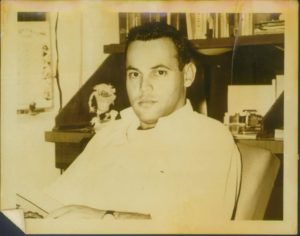

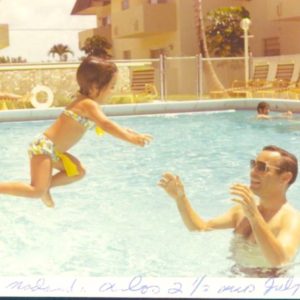

It has been more than a month since I watched my father draw his last breath. That day I fed him his last meal, spoon by spoon, and I thank God for that gift. He signed to my mother to comb his bit of hair. To the end he was an elegant, old-world Cuban of a type which is almost extinct. He smiled on all of us — reassuringly, bravely, lovingly — and then he left us.

I don’t doubt that God pitied us in the sorrow of that moment. Perhaps, I wonder, he even wept again.