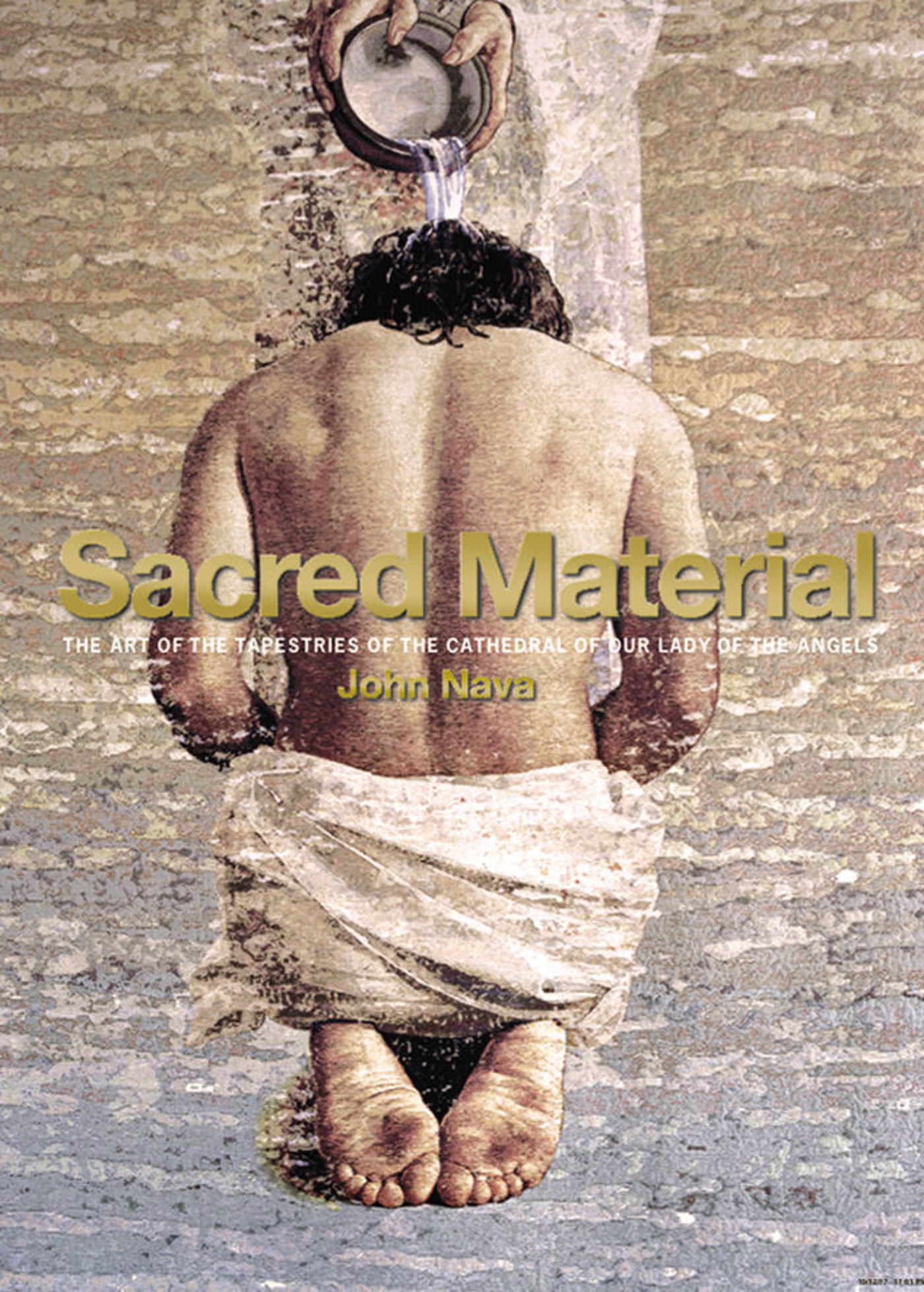

With their ties to ancient churches, John Nava’s tapestries tell the stories of our sacred ancestors and the varied rnpathways that lead to God

A tapestry is to church architecture as music is to liturgy, an evanescent beauty evoking the eternal. Woven textiles wafting with passing breezes complement the sturdy stone edifices just as music exalts the Real Presence during the Eucharist. The Church militant — pilgrims in the here and now — processes toward eternity.

Originally, John Nava’s tapestries for the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels in Los Angeles were commissioned to enhance the musical quality and acoustics of the vast space. Engaging with this ancient technique, however, so significant in the history of church décor, Nava breathed new life into an old and almost forgotten art form.

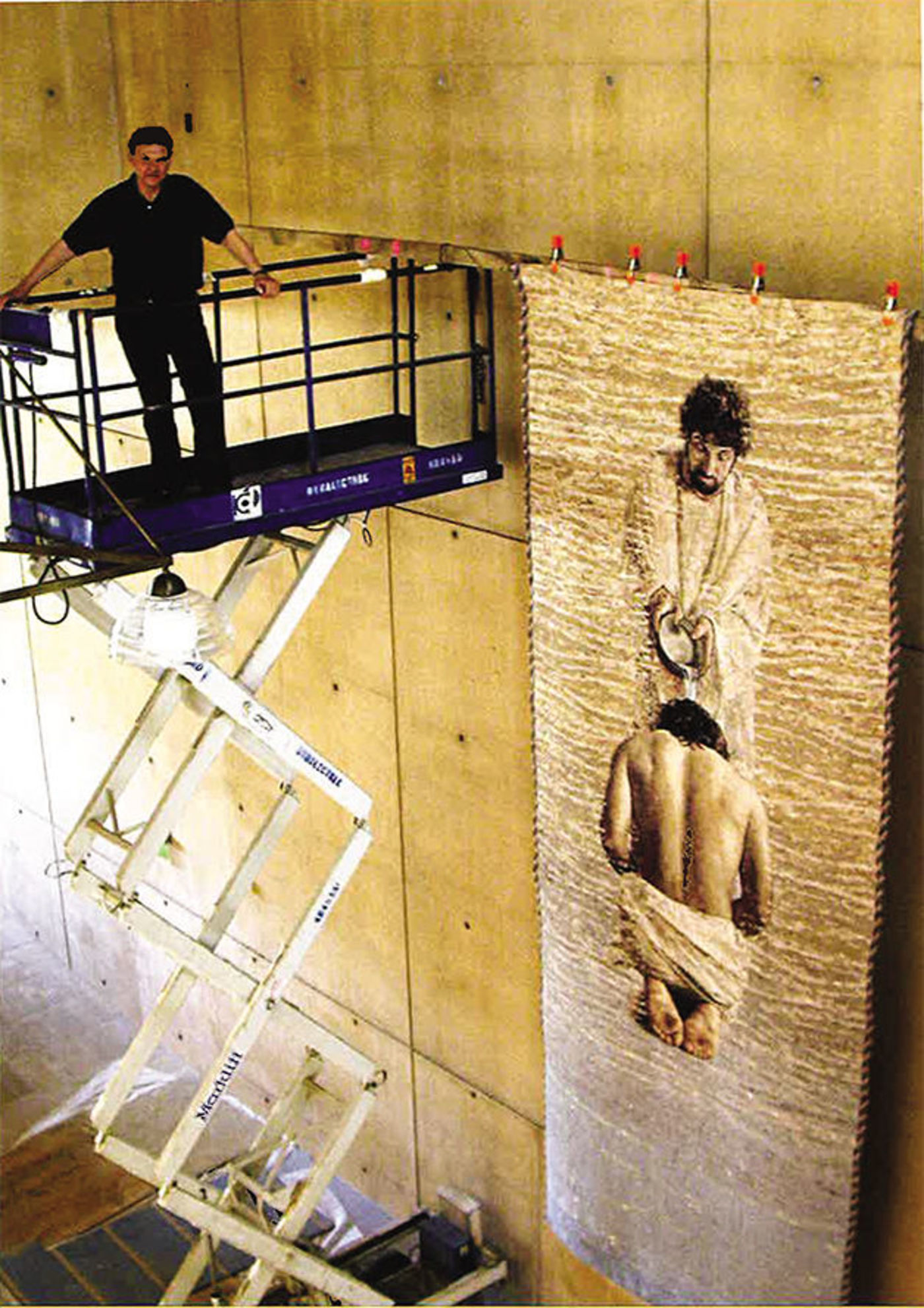

Technology met tradition, and meaning returned to media in the extraordinary series of 37 tapestries produced from 1999 to 2002. Twenty-five draperies line the walls with 135 Catholic saints; five panels surmount the baptismal font and the seven above the altar lead the faithful to the holy city, the celestial dwelling.

rn

rn

rn

Immutable and enduring

Throughout the Mediterranean basin, the cradle of Christianity, the ancient peoples used architecture to represent the immutable and enduring. The human longing for eternity produced the majestic pyramids, ziggurats and temples that still inspire awe today. When Emperor Augustus transformed the Eternal City from “a city of brick into a city of marble,” erecting the first temples to men-turned-gods, he turned to the architect Vitruvius, whose formula for great building was beauty, utility and endurance.

For their part, Christians, after their stint in the early house churches, were quick to seize upon the opportunity of political toleration to build powerful structures in stone, offering stability as well as space, so that all would feel welcome inside the mighty house of the Lord. Nava’s tapestries recall this with their inscription over the altar from Revelation: “God’s dwelling is among mortals. God will dwell with them” (Revelation 21:3).

Tourists love to visit the stone churches of the Old World, particularly in the summer when the cold stone serves as natural air-conditioning. They enjoy the decorations made of stained glass, mosaic or fresco and marvel at their age. Almost as durable as the buildings, these art forms often evoke the same sense of permanence as the masonry walls.

Within those walls, however, millions of lives have come and gone over the course of the centuries, with their struggles and losses, each person playing out his or her individual drama on the road to sanctity; some victorious and some not. Tapestries, like theater curtains, enveloped the vast community whose sacramental lives began and ended inside those spaces, each its own transient work of art.

Santa Maria Antiqua, the Roman guardhouse-turned-Christian church in the 7th century, bears the oldest evidence of the use of tapestries in churches. Along the ancient stone walls, anonymous painters lined the nave with faux draperies. The practice continued over the centuries, whether the murals of the Upper Basilica of St. Francis in Assisi or in the Sistine Chapel in Rome.

rn

rn

rn

Rich, textured effect

The tapestries of Our Lady of the Angels recall those venerable sites through the rich, textured effect of their backgrounds. As a medium, tapestry requires that every part of the surface be decorated: blank space is anathema to the nature of the technique. Medieval weavers used a “millefleur” effect (floral patterns) or the patron’s coat-of-arms or some other figurative device to fill the space around the scene.

Nava gave his backdrops an interwoven pattern of history, using images from the excavations of the Via Dolorosa in Jerusalem from the time of Christ along with neighborhood rocks, paper, chipped paint and rust to create a subdued yet textured surface.

The chalky shade of ancient limestone, embellished with spatters of faded paint, patina and print complements the smooth stone walls, but adds the venerability of age and the layers of living history through the myriad materials. The saints figured on them process from the past, from the limestone blocks of the Holy Land, away from the iron weapons of their martyrdoms through the colorful medieval churches toward Christ.

Nava’s nod to the Old World is also evident in the altar tapestry where he used a map of Los Angeles superimposed by cosmatesque circles. This technique using different stones from different countries cut into geometric shapes was invented by the Roman Cosmati family in the 12th century. The myriad colors arranged in circles signified the universal Church, spread over many nations, but united in Christ. Nava updated this ancient symbol for the culminating point of the cathedral.

rn

rn

rn

Tapestry is an art of collaboration, bringing many hands together to work toward a common goal. Designers, weavers, thread producers and patrons all contributed to the success of the finished product. As the Renaissance dawned throughout Europe, patrons increasingly demanded narrative tapestries and as a result the collaborations grew more international.

Weaving towns like Bruges, Arras, Tournai and Lille worked with English merchants for wool, bought silk from Spain and dealt with Venice or Cypress to obtain precious gilt threads. Patrons also came from further afield, including Francis I and Frederick II of Denmark, and Italy became the hub for designers, with Italian painters producing the cartoons for many of King Henry VIII’s 2,450 tapestries.

Arguably the greatest collaboration of the age was the production of 10 tapestries commissioned by Pope Leo X in 1515, which were designed by the brilliant Raphael Sanzio and woven by the Bruges workshop of Pieter van Aelst.

Destined for the Sistine Chapel, they were ambitious in scope, exquisite in production and precious in material (costing five times the amount paid to Michelangelo for the ceiling three years earlier). These works seamlessly knit together Italian narrative power with the skill of Belgian weavers.

A Venetian diplomat writing in the 16th century claimed that the Netherlands excelled in three things: fine “linens in Holland; beautiful figured tapestries of Brabant [Belgium]; the third is music, which one could say is perfect.”

Collaborative endeavor

rn

rn

rn

The tapestries of Our Lady of the Angels revived that tradition of collaboration when John Nava contacted the Flanders Tapestry company near Bruges. Two brothers, Roland and Christian de Keukelara, had developed a method of using Jacquard loom technology to read digital files.

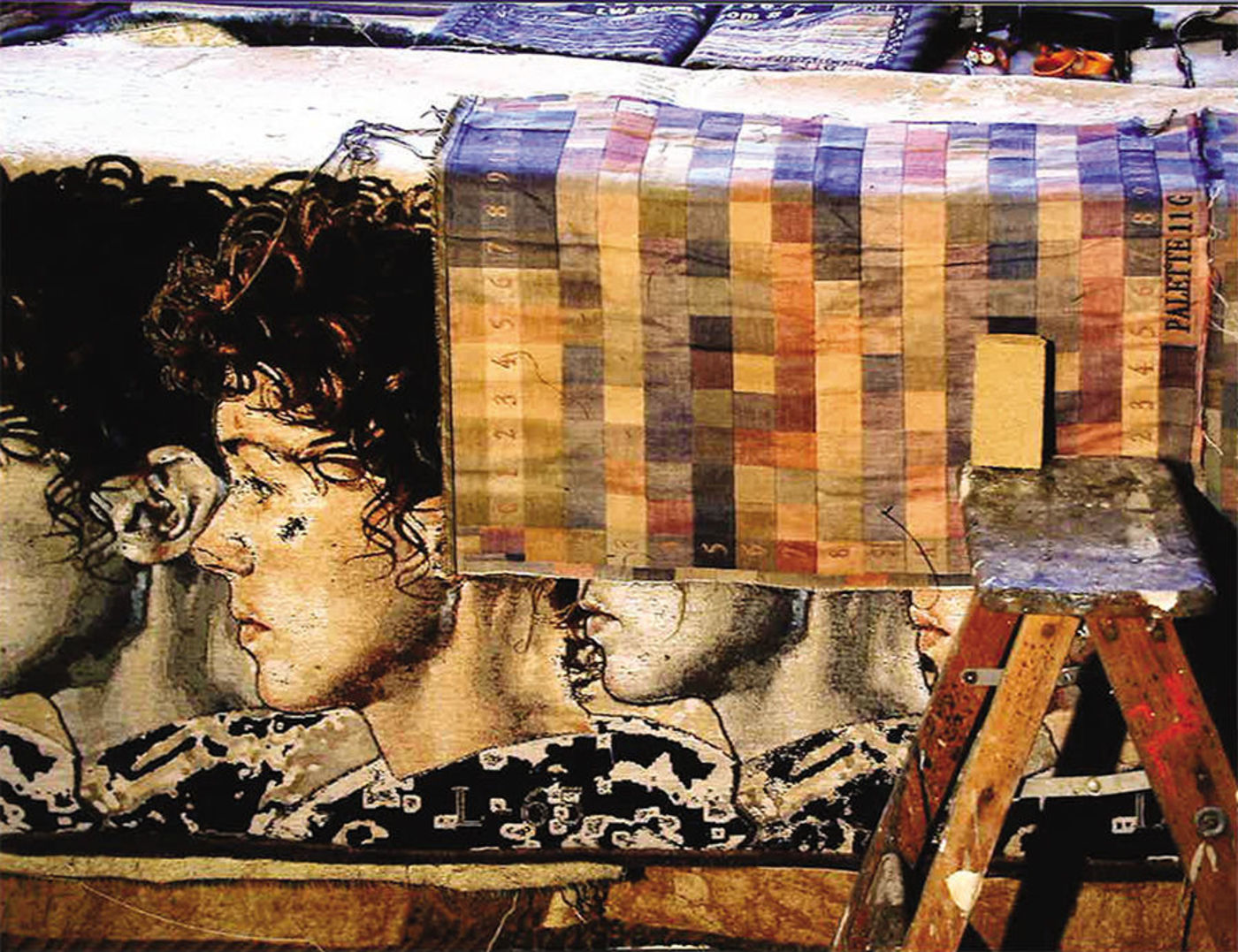

The skill of Donald Farnsworth digitized Nava’s images to be sent to the de Keukelara brothers for weaving. Using a palette of 240 hand-selected colors, the tapestries were woven at about 65 shots per centimeter. Raphael’s Sistine tapestries, by contrast, were woven at seven warps per centimeter, then considered the finest weaving of the day.

Italian artist/historian Giorgio Vasari described the difficulties of designing tapestries in his “Lives of the Artists” published in 1550. “There must be fantastic inventions and a variety of compositions in the figures. These must stand out one from another, so they may have strong relief, and they must come out bright in the colors and rich in the costumes and vestments.”

John Nava’s wool and viscose tapestries may not boast the opulent palette of silk and gilt threads, but the subdued variety and richness speak to an age no longer dazzled by brocades. His “fantastic inventions” are those of the Lord, the great variety of faces that form the rhythmic pattern of 135 saints.

Representing every age, every color, every size, Nava’s procession of holy men and women illustrates the universal Church in all its diverse glory. To produce this rich tapestry of visages, Nava poured over old photographs, death masks, famous paintings, and even hired a casting director to find contemporary faces that would seem more familiar to viewers.

Ancient saints seem like old friends, and the youthful loveliness of Cecilia, Perpetua and Felicity underscores the poignancy of their persecution. Nava also added a number of local children to the procession, the hopeful promise of future saints.

rn

rn

rn

The Renaissance Church used tapestries for single occasions — a series for Easter or Christmas to be hung for a brief period and then stored away. Like the hymns sung for the Nativity or the chants of the Resurrection, tapestries provided ethereal beauty that could be altered, as opposed to the stone walls and mural frescoes fixed in place.

After the Protestant Reformation, tapestries became even more important. As the printing press distributed pamphlets, figurative wall hangings visually reinforced beliefs inside sacred spaces. Henry VIII commissioned a set recounting the “Stories of David” after his break with Rome, while Pope Leo X’s tapestries reaffirmed the importance of St. Peter after the rupture with Martin Luther.

Nava’s tapestries also send a powerful message of transience amid permanence. Baptized in Christ, hundreds of men and women lived their short time on earth, each with a distinct story in different places and different times, but race, geography, gender, age, status aside, they all found the same path that led them to the city of the Lord. The worshippers, standing alongside these saints in the nave, are headed on the same path, all part of the same heavenly choir.

Interested in more? Subscribe to Angelus News to get daily articles sent to your inbox.

Elizabeth Lev is an American-born art historian who lives and teaches in Rome. She has served as a commissioner and consultant on art and faith for the Vatican Museums. Her TED Talk on the Sistine Chapel has garnered more than 1.3 million viewers. Among her books are “The Tigress of Forli: Renaissance Italy’s Most Courageous and Notorious Countess, Caterina Riario Sforza de’ Medici” (Houghton Mifflin, $10) and “A Body for Glory: Theology of the Body in the Papal Collections” (Musei Vaticani, $50).