Seventeenth-century naturalist Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1717) was a woman way ahead of her time.

Boris Friedewald’s “A Butterfly Journey” charmingly recounts the story of this astonishing scientist and artist. The book includes more than 30 full-page color copper plates of Merian’s gorgeously detailed work.

Born in the German town of Frankfurt am Main to a family of engravers, publishers, and printers, young Maria was surrounded from an early age by illustrated books about exotic travel, New World landscapes, sumptuous gardens, and still lifes of fruit and flowers.

Her stepfather, the well-known painter and art dealer Jacob Martel, had painted entire books of tulips and filled the house with images of luxurious bouquets. One showed a rose with outside petals of purest white and a heart of blood-red, surrounded by a tulip, violets, lilies-of-the-valley and a butterfly perched on the tip of the branch. It could have been a rudimentary template for the work that would consume Maria’s life.

By the age of 13, she was already enamored of beetles and worms. The “wondrous present” of a few flour-white caterpillars rocked her world. Unbeknownst to Maria they were silkworms. She fed them lettuce, then watched fascinated as they spun their cocoons, changed into pupae, and finally emerged as moths that laid eggs and started the process all over again.

The magic! The metamorphosis! In those days people still associated worms with witchcraft, but Maria was hooked.

She created a secret studio in her parents’ attic, away from the prying eyes of her mother, who felt Maria should confine herself to embroidery and cooking. There, she used a quill to painstakingly draw the tulips she swiped from a neighbor’s garden, and taught herself how to paint on parchment in oils and watercolors.

Moved perhaps by the Luther Bible her late father had illustrated with engravings in 1630, she saw all of creation as evidence of God’s divine love and plan. In addition to flowers, she studied illustrations of crabs, snakes, dragons, storks, and frogs — but butterflies were always her first love.

She scoured the surrounding fields and hedges for her own caterpillar specimens, raising them in an ever-proliferating warren of plywood boxes. People started bringing and sending her more. She learned how to engrave copper plates.

At 18, she married her stepfather’s pet pupil and eventually bore two daughters. Johanna Helena and Dorothea Maria both followed in their mother’s artistic footsteps.

Her husband wasn’t much able to sell his art, so in order to support the family Maria taught — and created her own art. In 1679, she published a book about caterpillars that featured a revolutionary concept: plates showing the entire life cycle of a particular specimen from the larva and the plant upon which it foraged, to the chrysalis, to the mature butterfly. In 1680, she launched “The New Book of Flowers,” again aimed at both the artist and the scientist.

By 1682 she was estranged from her husband; they eventually divorced. In 1699, at age 52, Maria Sibylla sailed with her oldest daughter to the South American Dutch colony of Suriname. The climate was unbearably hot and humid, a breeding ground for malaria and other tropical diseases. The area also teemed with exotic insects, snakes, birds, lizards, spiders, and Merian’s beloved caterpillars and butterflies.

Enlisting the aid of native guides and enslaved persons, she ventured into the rainforest. Along the way, she learned the uses of hundreds of herbs and plants, as well as of the brutal treatment of the men and women forced to work on the sugar plantations.

“Indians, who are not well treated by their Dutch masters,” she wrote, “use the seeds of the peacock flower to abort their children, so that their children will not become slaves like they are.”

She lasted two years in Suriname, a remarkable feat given the conditions of the time, and sailed back surrounded by her voluminous collection of notebooks, journals, and drawings. Animal specimens floated in glass jars and piles of plywood boxes were sealed with Portuguese lavender oil to repel devouring insects.

Back in Germany, she toiled ceaselessly for the next 15 years. A 1719 edition of “The Metamorphosis of the Insects of Suriname” (originally self-published in 1705) is housed in the library of the Getty Research Institute.

She died more or less penniless, having poured out her lifeblood in the riot of colorful blooms, pupa, caterpillars, butterflies, and fruit she left behind for the delight and instruction of the world.

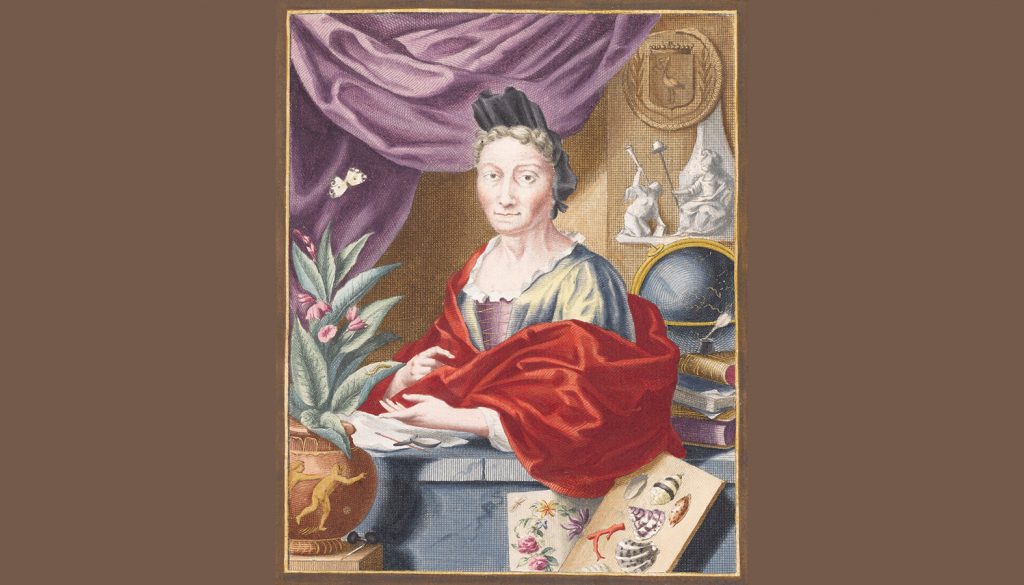

Notes Friedewald of the portrait Merian’s son-in-law painted shortly before her death:

“It shows Merian surrounded by all that she lived for. Right by her side is a butterfly; in the foreground a plant. Nearby is a plate with a seashell study and next to that is a floral bouquet painted by Merian. In front of her, a piece of parchment awaits ink and paint, and her books are stacked on the table. Taking a firm spot behind her is the globe, across which she traveled. Hanging over it is her family crest of a stork holding a snake in its beak. Sitting peacefully beneath it, on equal terms with Maria Sibylla Merian, is Athena, the goddess of war, victory, and wisdom, and the patroness of knowledge and the arts. And next to her, a winged female genius sounds a fanfare of joy.”