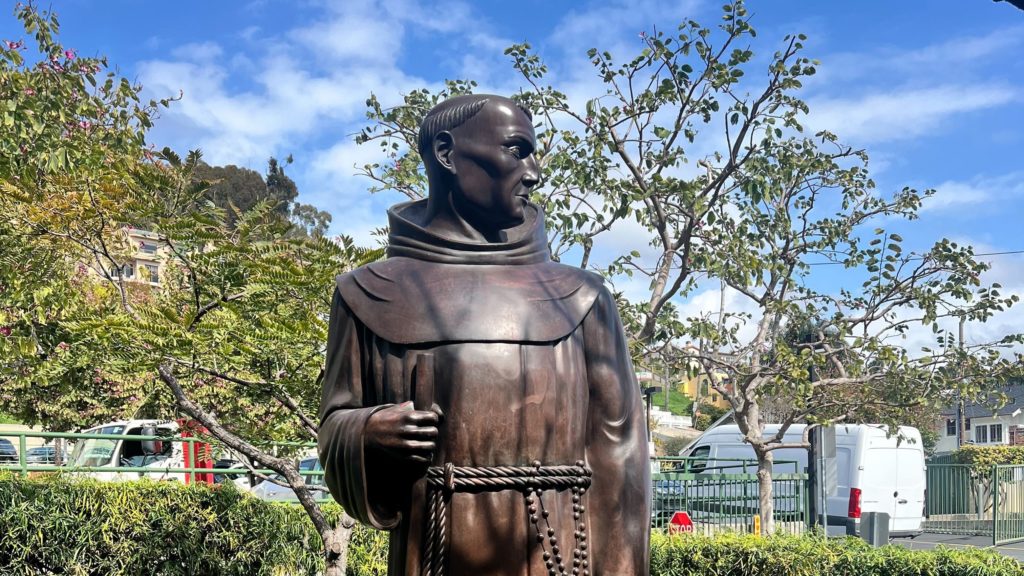

On Feb. 29, a larger-than-life-size bronze statue of St. Junípero Serra came home to the last of the nine missions that the 18th-century Spanish missionary founded: the Mission Basilica San Buenaventura.

The return of the statue from Ventura’s city hall, originally driven by disputes over Serra’s legacy and threats to deface or destroy his image, is a remarkable example of cooperation between the Catholic Church, Chumash tribal leaders descended from those who built the mission in 1782, and civic leaders committed to building community rather than tearing it down.

The cooperation occurred despite significant differences over the meaning and impact of Serra’s legacy. The Catholic Church, which canonized him in 2015, maintains that history shows him to be a loving evangelist who strove to protect Indigenous Californians from abuse by the Spanish military.

“On the ancestral land of the Chumash, Serra sought to be a spiritual father to the Indigenous people in Alta California,” said Father Thomas Elewaut, pastor of the Mission Basilica San Buenaventura and director of Historic Mission Sites for the Archdiocese of Los Angeles.

“It is fitting that his image will continue to involve peaceful and open dialogue regarding the history of the Indigenous people, the mission era, the Spanish conquest, the Mexican occupation, the Gold Rush, and finally California statehood in the United States of America, all of which have impacted and influenced the history of this land.”

Recently, the mission created a GoFundMe campaign to raise $30,000 for the transfer, reinstallation and adjacent landscaping of the Serra statue.

Franciscan Father Junípero Serra came in 1769 to what was then the northernmost frontier of New Spain, along with a small contingent of Spanish troops, to try to convert the peoples of Alta California to Christianity.

His method of protecting them from the sort of violence and exploitation Native Americans had suffered earlier in New Spain was to build missions organized around the traditional monastic rhythms of work and prayer. Some historians have compared the work done at the missions in that period to slavery, particularly given 18th-century European disciplinary practices that included stocks, whipping, and shackles.

After Serra’s death in 1784, the Franciscans built 12 more missions over the next 40 years. All 21 missions were secularized by the Mexican government in the mid-1830s. Most quickly fell into ruin and were only restored decades later. Though diseases that were not understood two centuries ago began to kill Indigenous Californians during Serra’s lifetime, the overwhelming percentage of Indigenous deaths — due to disease, violence, and related maltreatment — occurred after secularization.

The death and marginalization of Indigenous Californians “had a layering effect,” Elewaut said. “It’s not just the missions and it’s certainly not Serra, in my opinion. He defended their dignity and rights.”

This statue of Serra, which stands over 9 feet high and weighs about 3,000 pounds, was cast in 1988 to replace a concrete original that had stood in Downtown Ventura since 1936. It was unveiled in front of Ventura City Hall on October 20, 1989.

Long-simmering debates about Serra’s impact on the First Peoples of California boiled over in the summer of 2020. Protests over the police killings of George Floyd and other unarmed Black persons led to attacks on statues that honored defenders of slavery. Some protesters saw Serra as part of that legacy.

Matt LaVere, now a Ventura County supervisor, was mayor of the city of Ventura at the time.

“We had received some actionable intelligence through our police department that there were plans to come and tear down or deface the statue here,” he said.

“At that point I realized, that’s the last thing I wanted.”

He decided to contact both Elewaut and Julie Tumamait Stenslie, then the longtime tribal chair of the Barbareño/Ventureño Band of Mission Indians, whose proper name is Chumash. Meanwhile, Elewaut had already received a call from Tumamait Stenslie, who has since stepped down from her tribal role and could not be reached for this article.

Despite deep disagreements over the ministry of Serra, they had a longstanding respectful relationship. Both firmly believed that the Chumash had built Mission San Buenaventura on Chumash land and that only the Chumash people had the right to address how the mission affected Chumash heritage.

She called to tell him that social media was filled with calls for a protest to take down the statue in Ventura. “She said, ‘I think you and I and the mayor should all get together and talk about this,’ ” he recalled.

They met for hours at city hall.

“I think, at the end of the day, we all wanted the same thing,” LaVere said. “We didn’t want the statue torn down or defaced. We wanted to protect the statue but look at keeping it in an area where it wasn’t so in-your-face to residents who had different beliefs.”

Moving it to the mission was a logical solution. But there were hurdles to overcome.

On June 18, the three issued a joint letter on the City of Ventura letterhead, stating that “the three of us are confident that a peaceful resolution regarding the Father Junípero Serra statue can be reached, without uncivil discourse and character assassination, much less vandalism of a designated landmark.”

The decision, they wrote, must involve the City Council, the Chumash tribe and Ventura residents.

“To honor the cultural heritage of Ventura and its earliest residents is our ultimate goal,” they wrote.

“We all believe that the removal of the statue should be accomplished without force, without anger, and through a collaborative, peaceful process.”

Protesters arrived the next day. Their leaders were prepared to let Tumawait Stenslie speak, but not Elewaut. She gave him the chance by calling him to the microphone as she finished speaking.

Her own remarks, which included criticism of the missions, had also been pointed about who had a right to determine the fate of the statue.

“She said, ‘This is our challenge,’ ” meaning the Chumash, she recalled. She told the protesters who were not Chumash and who did not come from Ventura that they should stay out of it.

That July the City Council voted to store the statue until it could be removed to the mission. However, a lawsuit by local people who wanted it to stay at city hall caused a three-year delay. While Elewaut appreciated their concerns, “If you put the statue back up, how long do you think it’s going to be there?” he asked. “I wanted to preserve the statue.”

Once the legal battle ended, moving the statue has required major preparations, including erecting a new base, and flexible planning to accommodate weather, traffic, and even a last-minute change of contractors.

LaVere looks forward to seeing the statue in its new home.

“It took a lot of courage for Father Tom and Julie,” he said.

“Both of them took some blowback from it from their respective camps. I have an immense amount of respect for both of them that they were able to come to this agreement, to this decision and this opportunity.”