In May 2018, I spontaneously decided to begin walking the roughly 800-mile California Mission Trail. With a lot of prayer, support from my family and friends at the California Mission Walkers, I finished in June 2020.

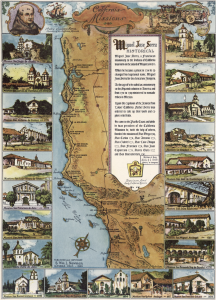

I first visited California’s 21 missions, founded by Spanish Franciscans between 1769 and 1823, by car when I was single. After I was married and started a family, we often pulled over to visit a mission while on road trips.

But it was walking this American “Camino” that truly helped me understand what writer Richard Rodriguez said of the impact of the missions: “To live here [California] is to submit to the names, to the ruins of a Spanish adventure, to live among Spanish. To live here is to become, implicitly, a Catholic, culturally a Catholic” (Los Angeles Times, Sept.13, 1987).

In light of the jubilee year marking the 250th anniversary of Mission San Gabriel Arcángel, it is worth understanding the mission’s pivotal role in the evangelization of California, and what set it apart from the other missions.

If we were to ask the mission’s founder, St. Junípero Serra, he might start by describing the mission as one of his more challenging ventures.

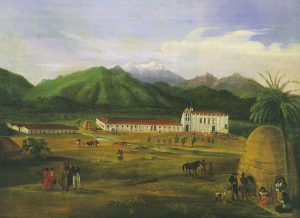

Mission San Gabriel did not develop the way the Spanish missionaries had initially envisioned. The original mission was established Sept. 8, 1771, by Fathers Pedro Cambón and Angel de la Somera, in present-day Montebello. Shortly after, however, the planned site was moved to its current location on higher ground due to flooding.

In a 1944 special edition of The Tidings devoted to St. Junípero, the author describes the relocated mission as “lying in the foothills of a great mountain range ... unsurpassed for beauty and fertility of soil.”

But back in 1772, less than a full year after its founding, the mission seemed high on the list of the future saint’s worries.

“This mission [San Gabriel] gives me the greatest cause of anxiety,” St. Junípero wrote in a letter to his guardian in Mexico City, Father Rafael Verger. “The secular arm down there was guilty of the most heinous crimes, killing the men to take their wives.”

And yet despite all the difficulties that Mission San Gabriel would face throughout the years — floods, fires, and earthquakes among them — the undaunted spirit of the people of Mission San Gabriel persevered.

Even though I had taught high school California history and written books and articles about Catholic history in Spanish and Mexican California, walking in the footsteps of those who blazed the trail before me — indigenous, Spanish, and “mestizo” — helped me appreciate more deeply what Pope Francis shared during his homily at the canonization Mass of St. Junípero in September 2015. He spoke of a Church “which goes forth” and along the way I encountered histories of many Catholics who did just that, literally.

Located at what would eventually be a crossroads between the Spanish missions in the Southwest and those on the Pacific coast, Mission San Gabriel was often a beehive of activity. This would have never happened if it were not for the 238 men, 78 of whom were soldiers, sent by the Spanish government in 1769 to fend off any possible interlopers.

“Although small in size, these outposts [presidios located at San Diego, Monterey, and Santa Barbara] would represent Spain’s claim to the region if challenged by England, Russia, or another imperial power,” wrote California historian Albert Greenstein in 1999.

The plan was pretty unique: Rather than send colonists from the home country, the local natives would be converted to Catholicism, thus in turn making them citizens of Spain. But progress was slow at first. Father Junípero pleaded with the Crown to send married soldiers and their families. He believed that they would be positive role models to the natives. The Crown agreed.

On March 22, 1774, with the help of American Indian guides, Captain Juan Bautista de Anza and his expedition, including Father Francisco Garcés, reached Mission San Gabriel after scouting an overland route for colonists to take to the fledgling Spanish missions along the Pacific coast.

The next time Father Garcés (whom history remembers for naming the Colorado River and for being the first European to explore California’s Central Valley) returned to Mission San Gabriel later that same year, it was with his old friend Fray Junípero, who he had met in Mexico six years earlier. The two friars walked the hundred miles between Mission San Diego de Alcalá and Mission San Gabriel together, battling rain and mud most of the time. It took them six days.

On Feb. 12, 1776, after crossing the Sonora and Mojave deserts, 30 families (240 men, women, and children) of the Second Anza Expedition, whose eventual goal was to colonize San Francisco, reached Mission San Gabriel. According to the National Park Service, the “[colonists] reflected the diverse castes of Spanish society, a mix of Native American, African, and European heritage.” Like so many immigrants today, at great cost, they came seeking a better life.

More immigrants arrived on Aug. 18, 1781. Eleven families from Loreto came to the mission to set up Pueblo de los Ángeles, the second “pueblo” (“town”) created during the Spanish colonization of California, the first being San José in 1777. Roy E. Whitehead, M.D., describes the nine-mile journey made on Sept. 4, 1781, to found the new “pueblo” in his 1978 book “Lugo: A Chronicle of Early California.”

“The parade started with Sergeant Jose Anton Navarro leading, carrying the image of Our Lady of the Angels, followed by Corporal José Venegas with the Holy Cross, followed by Private Luis Quintero holding up the banner of Spain. Then came the governor [Neve] with Fathers Crurado and Sanchez of San Gabriel, attended by Indian acolytes. The eleven settler families walked behind with their twenty-two children, followed by soldier guards on horseback. These dragoons wore leather jackets and carried lances swinging from their arms, and oval rawhide shields hung from their saddlehorns. Numerous Indians brought up the rear, driving horses, mules and cattle which were the stock for the colonists to use during their probation period. They arrived at an outdoor altar which had been constructed prior to their march. The priests came forward and recited the mass, with the large congregation in a semicircle around the altar (86-87).”

Since 1981, descendants of the families, known as “Los Pobladores,” and friends have walked the route during the Labor Day weekend.

Pilgrimage walks can be a powerful way to deepen one’s faith during this jubilee year for the Archdiocese of Los Angeles. Doing so will help one work toward a spiritual goal. What was powerful for me was coming to a deeper realization that I do not walk alone during this earthly pilgrimage. I walked the same routes traveled by Catholics who came before me — indigenous, Spanish, and “mestizo.” Their faith was stronger than any fear of what tomorrow could bring for them.

Mission San Gabriel has been through a lot in its 250 years. One of my favorite stories is of the painting “La Dolorosa” (“Our Lady of Sorrows”): When local Indians upset by the Spaniards building a mission in their backyard were shown “La Dolorosa,” they were pacified by its beauty. (The story about its theft in 1977 and recovery in 1991 is pretty miraculous, too.)

Floods, the epidemic of 1827-1828, and earthquakes in 1804, 1812, and 1987 come to mind. Of course, there was the 2020 fire. Miraculously, “La Dolorosa” was unscathed, safely in storage.

Each time, though, the people, many baptized in the mission’s hammered copper font gifted by Spain’s King Carlos III in 1771, respond. They go forward in mission, an endeavor spearheaded by hope. Like Zechariah, Gabrieleños and Angeleños are consoled by the words of Archangel Gabriel: “Do not be afraid ... because your prayer has been heard” (Luke 1:13).