The year 2020 will mark 25 years since the Vatican published its list of 45 “best films” to commemorate the centennial of cinema. They were divided into three categories: religion, values, and art.

The first part of this series, published in the Nov. 22-29 issue of Angelus, looked at a few of the films in the “religion” category. This week, we look at the category covering movies about “values.”

‘Chariots of Fire’ (1981)

Hugh Hudson’s 1981 drama “Chariots of Fire,” inspired by the real-life story of two British sprinters at the 1924 Olympics in Paris, takes its title from a line in the William Blake poem, “And did those feet in ancient time.” Blake’s work refers to the story of Old Testament prophet Elijah in 2 Kings 2:11, who is taken to heaven in a “chariot of fire.”

This biblical premise is felt in Eric Liddell (played by Ian Charleson), the Scottish missionary who sees running as a testament to his profound love for the Lord. “I believe that God made me for a purpose, but he also made me fast. And when I run, I feel his pleasure,” he tells his sister in one moving scene.

Liddell's Christianity becomes a source of contention with the Prince of Wales and the British Olympic Association when he refuses to race on the Sabbath. He ultimately prevails, never once wavering from his faith.

The film’s other protagonist, Harold Abrahams (Ben Cross), is a Jewish student athlete at the University of Cambridge, subjected to anti-Semitic treatment. While Liddell can’t contain the sheer joy he feels while running, Abrahams’ face is sharp and focused.

He has something to prove. “Do you love it?” Abrahams’ girlfriend, Sybil (Alice Krige) asks him. “I’m more of an addict. It’s a compulsion with me, a weapon I can use,” he replies.

If Hollywood released “Chariots of Fire” today, the film would have all the trappings of sports cinema clichés, pitting the runners against one another in a feverish battle for the win. Instead, here is a tale where two heroic men compete, largely, against themselves, striving toward a greater purpose.

The film is perhaps best known for its iconic, synth-heavy Greek composer Vangelis score and sweeping title track. It was a brave choice for a period drama at the time, and lends another transcendent element to Hudson’s heartfelt, inspiring film.

‘The Tree of Wooden Clogs’ (1978)

Director Ermanno Olmi’s Palme d’Or-winning film “The Tree of Wooden Clogs” drew on his own family’s stories about peasant farm life in Lombardy, Italy. The film was released 26 years after the neorealist movement, but its influence here is clear. Olmi cast real peasants from the Bergamo province who spoke a lost Italian dialect and filmed on location.

The alpine medieval town is a setting that artists through the ages have dreamed about on the page and canvas. A pastoral folktale brought to life, men wander through the woods singing to the wolves that lurk in the dark. Elders teach the young about the moon and banish demons from a roaring fire. The cool blue harvest landscape is picturesque, but the farmer’s life is far from romantic.

The title credits tell us that we are witnessing the trials of a typical tenant farm at the end of the 19th century, where four to five peasant families share lodgings, land, stables, and tools, most of which belong to the landowner who receives a hefty portion of everything sold.

Men hammer and dig at the land, sculpting a life that isn’t even fully theirs. Women are forced to choose between abandoning their children at the local orphanage or scrubbing laundry until their hands are raw.

Faith is the cornerstone of life in Bergamo. Prayers are uttered all day long, sick cows are healed by holy water, and wandering beggars are regarded as those closer to God. Olmi’s own working-class, Catholic roots have a strong influence here.

He offers a realistic portrait of a people longing for God’s graces who find moments of hope, beauty, and spiritual truth in their simple lives despite a suffocating oppression that seems to thwart them at every turn.

‘Bicycle Thieves’ (1948) / ‘Rome, Open City’ (1945)

“The Tree of Wooden Clogs” shares a desperate final act with Vittorio De Sica’s neorealist classic “Bicycle Thieves,” which reveals the harsh realities of life in postwar Italy.

In the tradition of the influential genre, De Sica cast his movie’s leads with nonprofessional actors: a factory worker, a journalist, and a child plucked from the crowd of onlookers during filming.

A destitute family’s fate hangs in the balance after the barely employed patriarch’s only mode of transportation is stolen. It’s no coincidence that the brand of the bicycle is named “Fides,” which means “faith.”

As hopelessness takes hold of the family, we are haunted by the increasingly questionable decisions made by the father that he can no longer conceal from his young son and the world around him.

Roberto Rossellini's “Rome, Open City,” a defining work of the neorealist movement, shares the harrowing tale of the Roman people during Nazi occupation in the capital city. Rossellini cast famous Italian actors (Anna Magnani and Aldo Fabrizi) with nonactors, including real German POWs.

Using the war-torn streets and crumbling architecture of Rome as his only sets, Rossellini depicts a united people in the resistance against evil and the sacrifices they make. Fabrizi’s ill-fated priest Don Pietro Pellegrini carries the burden of forgiveness for all.

‘Au revoir les enfants’ (1987) / ‘The Burmese Harp’ (1956) / ‘Schindler's List’ (1993) / ‘Gandhi’ (1982)

Stories about the enduring human spirit during times of war continue to figure heavily in the “values” category. Louis Malle’s film “Au revoir les enfants” shares a child’s perspective of the Holocaust. The events are based on Malle's own boyhood experiences at a Catholic boarding school in occupied France.

He witnessed a Gestapo raid at the institution, which saw three Jewish classmates, a Jewish teacher, and the school’s headmaster deported to concentration camps in Auschwitz and Mauthausen.

Kon Ichikawa’s Japanese drama “The Burmese Harp,” based on a children’s novel by Michio Takeyama, looks at the war from a different perspective. Buddhist symbolism abounds in the film about a Japanese soldier who finds what peace he can by living like a monk after fighting in the Burma Campaign during World War II.

In a 1972 interview with film scholar Joan Mellen, Ichikawa made his feelings about war clear: “War is an extreme situation which can change the nature of man. For this reason, I consider it to be the greatest sin.”

Steven Spielberg’s “Schindler's List,” based on the novel “Schindler’s Ark” by Thomas Keneally, is a tale of redemption. German businessman and Nazi Party member Oskar Schindler is transformed after witnessing the tragedies inflicted upon his Jewish factory workers by the Nazis.

Based on a true story, Schindler is credited with saving the lives of more than 1,000 Jews during the Holocaust by protecting them under his employ.

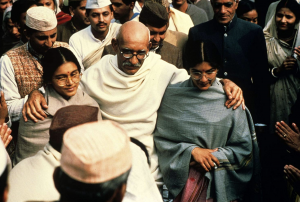

Ben Kingsley won an Oscar for his performance as Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, a leader of the nonviolent Indian independence movement against British rule during the 20th century. Director Richard Attenborough’s film explores similar themes of justice, unity, and faith when the human experience is pushed to the extreme.

‘Dekalog’ (1989–1990) / ‘Intolerance: Love’s Struggle Throughout the Ages’ (1916) / ‘Dersu Uzala’ (1975)

“Dekalog,” the 10-part television drama series from Polish auteur Krzysztof Kieślowski, is based on each one of the Ten Commandments. The chapters explore biblical themes through the moral conflict and spiritual dilemmas faced by a group of characters living in a Polish housing project.

Kieślowski told the press about the series, “Man doesn’t choose between good and evil. He chooses between greater and lesser evil.”

“Intolerance” shares four interwoven stories of injustice throughout the centuries using the crucifixion, the St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre, a modern American tale about a wrongful conviction, and the Fall of Babylon. In 1916, a show business trade paper Variety film critic said that “Intolerance” was “a powerful blow at the hypocrisy of certain forms of our up-to-date philanthropy.”

Acclaimed Japanese filmmaker Akira Kurosawa’s first film in his non-native language is an adaptation of a memoir by Russian explorer Vladimir Arsenyev, about his trek through the Siberian wilderness with Nanai trapper and hunter Dersu Uzala.

The humanist spirit of the film is portrayed through the growing relationship between the wildly different men as they navigate dangerous terrain and Kurosawa’s reflections on progress.

‘It’s a Wonderful Life’ (1946) / ‘On the Waterfront’ (1954)

Frank Capra's familiar Christmas tale “It's a Wonderful Life,” starring James Stewart as a broken man whose spirit is renewed thanks to his guardian angel, is a family classic. The Vatican’s film list cited it as an “unabashedly sentimental picture of mainstream American life ... bolstered by a superb cast and a wealth of good feelings about such commonplace virtues as hard work and helping one’s neighbor.”

Corruption and violence on the New Jersey docks weighs heavy on Marlon Brando’s “coulda’ been a contender” ex-boxer who stands up to his shady union bosses in Elia Kazan’s “On the Waterfront.” On the subject of making movies, Kazan once told an interviewer, “I don't move unless I have some empathy with the basic theme. In some way, the channel of the film should also be in my own life.”

Kazan’s “On the Waterfront” was noted by critics as the filmmaker’s response to the backlash he faced after his damaging testimony before the House Committee on Un-American Activities in 1952 during the Hollywood blacklist.

‘Wild Strawberries’ (1957) / ‘The Seventh Seal’ (1957)

In 1957, two stunning Ingmar Bergman classics of world cinema were released just 10 months apart: “The Seventh Seal” and “Wild Strawberries.” Both films are grounded in Bergman’s existential handling of morality, temporality, and faith.

The first film is set during the Crusades after the Black Plague arrives in Sweden, and the second film is a reflection on age and the very nature of our existence. Bergman’s ability to capture the interiority of his characters allows audiences to also meditate on the films’ universally felt questions about life and death.