When my father was in the hospital for the last time, we shared our final days together with O.J. Simpson. Not just O.J., but also Johnnie Cochran, Jr., Robert Shapiro, Judge Lance Ito, Marcia Clark, Mark Fuhrman, Kato Kaelin, and the whole strange cast of characters that made up “the trial of the century.”

The trial was on constantly in the hospital. My dad was watching it from his bed, and if we left the room, it was playing out in the waiting rooms and lobby. It was relentless.

It seems hard to recreate how all-consuming the murder of Nicole Brown Simpson and Ronald Goldman, the subsequent arrest and trial of U.S.C.’s greatest running back, Hertz pitchman, and actor Orenthal James Simpson was, especially in Los Angeles. The whole city was the set for this reality TV show.

A friend was commuting on the 405 Freeway when he saw in the opposing lanes the slow-motion chase of the white Ford Bronco followed by a host of news helicopters broadcasting the whole bizarre event live. He said the sight of the helicopters coming over the horizon made it seem like a scene out of “Apocalypse Now.” It was a bizarre preview to an equally bizarre trial.

Non-spoiler alert: What seemed like a slam dunk of a case surprised almost everyone with the jury finding Simpson not guilty. By and large, white Los Angeles was shocked and dismayed. Black Los Angeles was shocked too. They saw what can happen when you get the best legal defense team money can buy.

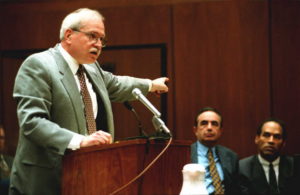

One of the less-famous members of that defense team was Gerald Uelmen, former dean of the University of Santa Clara law school. He was an expert on the California Evidence Code. In his book “If It Doesn’t Fit: Lessons from a Life in the Law,” Uelmen explains that he was the one who came up with the line, “If it doesn’t fit, you must acquit,” that Cochran used with such devastating impact in his summation.

In his essays on the O.J. trial, Uelmen lays out the defense strategy, which was simply to show that if the prosecution does not prove its case beyond a reasonable doubt, it requires the jury to acquit. He tells the story of one of the jurors who said she thought “’O.J. probably did it,’ but she understood that ‘probably’ wasn’t good enough, that she had to be convinced beyond a reasonable doubt.”

“The verdict,” Uelmen wrote, “was a vindication of the principle that guilt must be proven beyond a reasonable doubt.”

Uelmen is eloquent in his defense of the jury system, and he stresses the importance of a defendant getting the best, most capable defense possible. He is also not blind to the impact of racism on our legal system. O.J. was a wealthy man. He hired the best. If you are black and poor in America, your odds of acquittal diminish dramatically. He cites a range of statistics showing that one’s color makes a difference: “Whites do better at getting charges dropped. They’re better able to get charges reduced to lesser offenses. They draw more lenient sentences for the same crimes and go to prison less often.”

“When you are on the receiving end, it’s hard not to come to the conclusion that our justice system is far from color-blind,” Uelmen wrote.

Uelmen’s passion for a more just system includes his work in opposition to the death penalty. He has been a long-time board member of the Catholic Mobilizing Network, an organization that opposes the death penalty and supports restorative justice. (Full disclosure: I am also a member of CMN’s board.)

One window into the imperfections of our judicial system is the number of people, often on death row, who are exonerated. Last year alone, 153 were exonerated, including four on death row and 22 who were sentenced to life without possibility of parole. Eighty-four percent of these exonerations were of people of color; 61% were black.

Uelmen, as a Catholic and as a lawyer, judges the death penalty to be morally wrong. It is a position supported by the Catechism of the Catholic Church and the teachings of the last three popes.

Then what about O.J.? To say his life only got worse after his acquittal is an understatement. O.J. lost a civil case with a lower standard of proof. He served nine years of jail time for another crime.

Was justice ever served in this life for Nicole and Ron? No. The person who many of us think was their killer died April 10 of cancer.

It is an imperfect justice system, its imperfections most often exposed in its inequalities. It is one of many reasons to oppose the death penalty: While the guilty may occasionally go free, the possibility that the innocent would lose their lives at the hands of the state is infinitely more horrifying.