It's been nearly 25 years since the Vatican published its list of 45 “best films” to commemorate the centennial of cinema. Divided into three categories — religion, values, and art — many of the movies can hardly be classified as typical “Christian” films. The list, instead, celebrates many of those filmmakers and their works that reveal the interior human experience and explore our spiritual potential.

We can thank St. Pope John Paul II for that list. In a 1995 address to the Plenary Assembly of the Pontifical Council for Social Communications (now renamed the Dicastery for Communication), he emphasized the Church’s obligation as a longtime patron of the arts to take a positive, active role in “encouraging and promoting the moral vision which gives genuine content and inspiring expression to this art.”

Art, he stressed, should focus on “truth, goodness, and beauty.”

A list of “Some Important Films” was later released, compiled by then Archbishop John Patrick Foley, president of the council, along with a dozen cinema experts. The list has since been retitled the “Vatican Best Films List” on the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops’ (USCCB) website.

“It was not an attempt to canonize films, but it was an attempt to indicate what some good films are,” Foley told the press in 1996. A Catholic Moviefone-style 1-800 phone line was also created, which allowed the faithful to call in and hear descriptions of films reviewed by the USCCB’s Office for Film and Broadcasting. The now shuttered department had its own rating system for movies.

Cinemagoers and film critics worldwide have frequently returned to the Vatican’s film list through the decades, cementing its “best of” status with the Church. Time has been kind to most of the movies, given the Church’s emphasis on classic themes, art-house favorites, and Hollywood epics.

In a three-part series, we look at the Vatican’s list in its entirety, beginning here with the greatest films about “religion.”

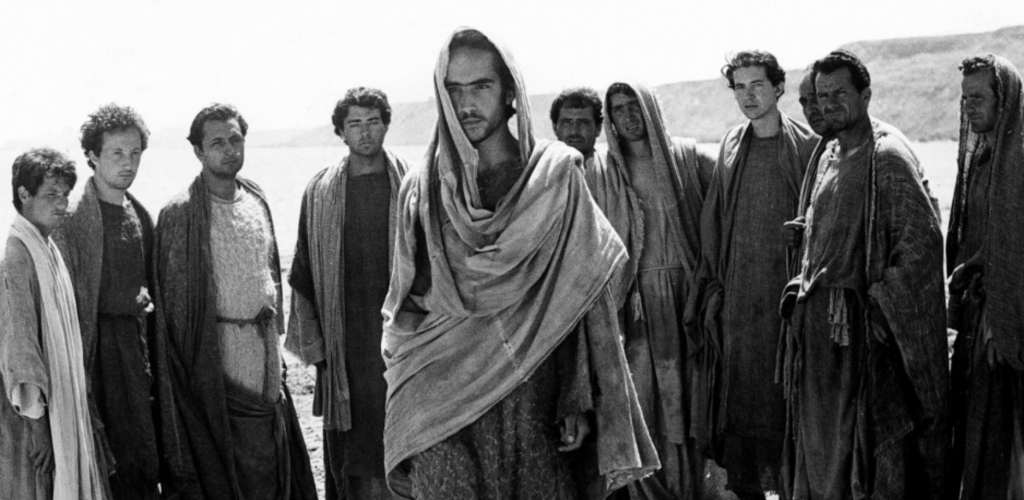

‘THE GOSPEL ACCORDING TO ST. MATTHEW’ (1966)

In 1962, Italian director Pier Paolo Pasolini, an unlikely pilgrim given his Marxist, atheist roots, found himself in the hometown of one of the Church’s most famous saints, Francis of Assisi, to attend a film seminar at the invitation of St. Pope John XXIII.

The pontiff wanted the Church to reach out to secular cultural figures just one year after Pasolini was brought up on blasphemy charges by the state for his short film “La ricotta.” The pope’s presence in Assisi excited the townspeople, and Pasolini waited out the crowds in his hotel room. There, he became engrossed in a copy of the Gospels. According to “Pasolini Requiem” author Barth David Schwartz, “it remained, alive and thriving within [him].”

The filmmaker chose to adapt Matthew’s writings for the screen, using no other dialogue but the apostle’s words.

Finding the landscape of the Holy Land too modernized, Pasolini looked to the geography of Southern Italy to film the movie. The terrain takes on a deeply sinister tone in a scene where Satan tempts Jesus in the desert. Mel Gibson would later film his “Passion of the Christ” in the same region, a movie that would surely join Pasolini’s on the list had it been compiled a decade later.

Nonactors filled the director’s ordinary cast, including his own mother as the older Mary. Pasolini’s disciples of Jesus bear the marks of his laborer and peasant players: craggy foreheads, dirty feet, Franciscan rags, and all. Nestled along the dusty hills, they sit absorbed in the radical teachings of Jesus, portrayed by teenage anti-Franco activist Enrique Irazoqui. His Christ is a defiant, fierce defender of the people.

The untraditional soundtrack transcends time and includes a Congolese choir, African American spirituals, and the classical sacred music of Bach. Eclectic flourishes are offset by a neorealist aesthetic: the cries of children (“Hosanna! Hosanna!”), the clopping of hooves, and the bustling of sweat-slick people. These deceptively simple choices give Pasolini’s film a time-tested authenticity that is candid and raw.

In 2015, the Vatican newspaper L’Osservatore Romano cited “The Gospel According to St. Matthew” as “the best film about Jesus ever made in the history of cinema.”

‘BABETTE’S FEAST’ (1987)

In a season of thanksgiving and community, Gabriel Axel’s “Babette’s Feast” has much to remind us about loving your neighbor.

Based on a short story by Danish author Karen Blixen (“Out of Africa”), elderly sisters Filippa and Martine keep their late pastor father’s memory alive in their pious, but dwindling religious community in 19th-century Denmark.

Immersed in their ascetic life along the gloomy Jutland seaside, the sisters take in French refugee Babette, who is seeking shelter from the bloody Paris riots. Though the sisters are unable to pay her, Babette agrees to work for free, cooking and tending to the townsfolk, brimming with charm and quiet determination. Straying from the sisters’ humble menu, Babette concocts an elaborate, celebratory dinner one evening that brings friends and lost loves together. In a selfless act, Babette’s glorious feast mends relationships as the earthly pleasures of fine wine and a decadent spread replenishes the souls of the villagers.

Pope Francis has referenced “Babette’s Feast” several times as his favorite film, even giving it a shout-out in his 2016 encyclical “Amoris Laetitia” (“The Joy of Love”):

“The most intense joys in life arise when we are able to elicit joy in others, as a foretaste of heaven. We can think of the lovely scene in the film ‘Babette’s Feast,’ when the generous cook receives a grateful hug and praise: ‘Ah, how you will delight the angels!’ It is a joy and a great consolation to bring delight to others, to see them enjoying themselves. This joy, the fruit of fraternal love, is not that of the vain and self-centred, but of lovers who delight in the good of those whom they love, who give freely to them and thus bear good fruit.” (AL 129)

As one character elaborates during a moving toast, “There comes a time when our eyes are opened and we come to realize that mercy is infinite. We need only await it with confidence and receive it with gratitude. Mercy imposes no conditions.”

‘BEN-HUR’ (1959)

MGM’s “Ben-Hur” is a Hollywood spectacle for the ages that could easily rival some of the biggest blockbusters today, if only in its sheer scope and rich craftsmanship in a pre-CGI era.

To create “Ben-Hur,” it only took director William Wyler some 300 sets, more than a million props, 100,000 costumes, 10,000 extras, 1.25 million feet of film all to the tune of $15 million ($133 million today).

Charlton Heston stars as the titular Jewish prince who is betrayed by his boyhood friend turned villainous Roman tribune (Stephen Boyd). Sentenced to slavery, Ben-Hur regains his freedom to battle the familiar foe. The centerpiece of the film is an epic chariot race, which pits good against evil in a tour-de-force series of stunts, thrilling camerawork, and larger-than-life set pieces.

The film’s pageantry aside, there are two particularly tender moments featuring a silent Jesus of Nazareth (we never see his face), who wipes the brow of a fallen Ben-Hur and gives him water. The two meet again during the crucifixion scene when Ben-Hur attempts to return the favor as Jesus is marched to his death.

“I spent sleepless nights trying to find a way to deal with the figure of Christ,” the director later stated. “Everyone already has his own concept of him. I wanted to be reverent, and yet realistic.”

Wyler’s emotional depiction allows viewers to remain quiet eyewitnesses to the astounding life and times of Jesus Christ.

Honorable mentions

‘ANDREI RUBLEV’ (1966) / ‘THE SACRIFICE’ (1986)

Enigmatic Russian filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky appears twice on the “religion” list. His film “Andrei Rublev,” about the 15th-century Orthodox monk and famed medieval Russian icon painter, takes an elliptical approach to the biopic and mirrors Tarkovsky’s own encounters with Soviet censors. Tarkovsky’s film “The Sacrifice” meditates on faith, compassion, and death. It would be the director’s final film.

‘THE PASSION OF JOAN OF ARC’ (1928) / ‘LA PASSION DE NOTRE SEIGNEUR JESUS-CHRIST’ (1907) / ‘ORDET’ (1955)

“The Passion of Joan of Arc,” Carl Theodor Dreyer’s stunning silent epic, uses stark black-and-white cinematography and breathtaking close-ups of star Renée Jeanne Falconetti’s face to portray the slain saint’s spiritual agony and ecstasy. Early French silent film “La Passion de Notre Seigneur Jesus-Christ” (also known as “La Vie et la Passion de Jésus Christ” and filmed in 1903) depicts stories from the Gospels but proves trickier to find a copy of. Dreyer’s drama “Ordet” also makes the list, bringing us back to the remote coast of Jutland featured prominently in “Babette’s Feast.” The austere family drama is based on a play by the Lutheran pastor Kaj Munk, who was murdered by the Nazis during the occupation.

‘MONSIEUR VINCENT’ (1947) / ‘FRANCESCO’ (1989) / ‘THE FLOWERS OF ST. FRANCIS’ (1950) / ‘THE MISSION’ (1986) / ‘THE MISSION’ (1986) / ‘NAZARIN’ (1959) / ‘A MAN FOR ALL SEASONS’ (1966) / ‘THÉRÈSE’ (1986)

The life of St. Vincent de Paul, great defender of the downtrodden, in 17th-century France is charmingly portrayed by star Pierre Fresnay with humor and sincerity in “Monsieur Vincent.” Liliana Cavani’s 1989 docudrama “Francesco” will be difficult for audiences of a certain age to suspend disbelief due to the casting of “9½ Weeks” actor Mickey Rourke. Roberto Rossellini's film “The Flowers of St. Francis,” co-written by Federico Fellini and beloved by Pasolini, is a much more inspired pick about the Franciscan. Devastating social and religious tensions are explored in “The Mission” and Luis Buñuel’s Palme d’Or-nominated film “Nazarin” (loved by Tarkovsky), while Academy Award-winner “A Man for All Seasons” and Cannes Jury Prize-winner “Thérèse” dramatize the lives of St. Thomas More and St. Thérèse of Lisieux.