June 16 is Bloomsday, the day when all the action takes place in James Joyce’s novel “Ulysses.” It’s observed especially in Dublin, Ireland, but also in Irish pubs around the world. The holiday is named for the novel’s protagonist, Leopold Bloom.

Among certain Catholics and literary scholars an argument will arise, as it does every year: Was he or wasn’t he?

Since the death of James Joyce in 1941, scholars have contended fiercely over the state of his soul. Anyone who’s read his work knows that it’s suffused with Catholic ritual, philosophy, doctrine, and culture. But why? Was Joyce writing as a Catholic? Or an anti-Catholic?

The poet T.S. Eliot held that Joyce’s work was “penetrated with Christian feeling.” And on Eliot’s side of the question stand media theorist Marshall McLuhan, novelist Anthony Burgess, critic Hugh Kenner, psychoanalyst C.G. Jung, and other cultural luminaries.

Joyce’s close friend, the writer and social critic Mary Colum, wrote that she had “never known anyone with a mind so fundamentally Catholic in structure as Joyce’s own, or one on whom the Church, its ceremonies, symbols, and theological declarations had made such an impress. ... The Scholastic was the only philosophy he had ever considered seriously.”

Joyce himself boasted, in a poem, that his mind had been “steeled in the school of old Aquinas.” He wept every year during the Holy Week liturgies. And the poet William Carlos Williams once saw him gravely refuse to lift his glass when a wag proposed a toast “to sin.”

And yet Joyce did declare himself apostate. To Nora Barnacle, the woman he would later marry, he wrote in 1904:

“Six years ago I left the Catholic church, hating it most fervently. I found it impossible for me to remain in it on account of the impulses of my nature. I made secret war upon it when I was a student and declined to accept the positions it offered me. By doing this I made myself a beggar, but I retained my pride. Now I make open war upon it by what I write and say and do.”

These words seem to undermine the case put forth by Eliot and others. And there is ample material in Joyce’s works to make the case that his “open war” raged on for decades. Though Colum believed the novel “Ulysses” to be “one of the most Catholic books ever written,” many Catholics condemned it as blasphemous and pornographic.

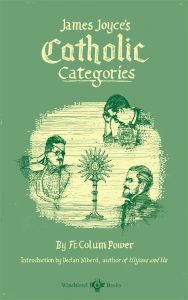

Now comes to the discussion Father Colum Power, a many-degreed scholar and priest of the Servants of the Home of the Mother. For readers of Joyce he has written an invaluable book: “James Joyce’s Catholic Categories” (Wiseblood Books, $50).

Wisely, Father Power has chosen to limit the question to what can be known. He does not place bets on whether Joyce wrote as a Catholic or whether he died in the state of grace. Indeed, he begins his study by acknowledging Joyce’s apostasy.

Joyce, baptized and educated as a Catholic, became an apostate. The goal is not to reclaim him for Catholicism, but to discover what kind of an apostate he became, how far his apostasy from Catholicism took him from religious belief. When faith is lost, how does Catholicism survive?

How does it manifest its lingering influence? Joyce was confoundingly capable of intense aversion and vehement diatribe toward the Catholic Church, and, almost simultaneously, of a nuanced and favorable disposition toward the historical Catholic contribution.

The subsequent discussion is substantial. Father Power’s book runs just shy of 400 pages, and it provides rich historical and biographical context for an informed reading of Joyce’s stories.

Father Power engages the relevant arguments about Joyce’s aesthetics. Was he a realist or a relativist? Do his unconventional narratives depict a world devoid of meaning and coherence, or a world so rich that it overflows the devices of conventional narrative?

Joyce’s most extensive reflections on art appear in his novel “A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man.” They belong to the novel’s protagonist, Stephen Dedalus, and it is at least debatable whether Joyce would claim them as his own.

It is fascinating, however, that Dedalus works out his aesthetics in the language of Thomism, the Christian philosophy Joyce had learned from the Jesuits at prep school. St. Thomas Aquinas himself composed no sustained treatment of aesthetics, so what Joyce places in the mouth of Dedalus is an original contribution, a synthesis that would be engaged by later philosophers, including Umberto Eco.

Joyce consistently appropriated the language of Catholicism — most famously, the word epiphany — to express his ideas about art. He spoke about the artist as “priest of the eternal imagination.”

In the course of his analysis, Father Power provides a close and sensitive reading of Joyce’s works; and in doing so he reminds us why we should care in the first place. Joyce’s stories and novels are heartbreakingly beautiful works of art.

His first book, “Dubliners,” was a collection of short fiction. Most of the stories are compact, the narratives spare, and every detail counts. Every detail signifies. Father Power has a genius for noticing the details and conveying their significance. He remarks, for example, on an easily glossed-over, quite common verb in the last sentence of “A Painful Case” — “He felt that he was alone.”

In the word felt, Father Power detects a final note of hope in a story most readers judge to be despairing. The protagonist, a man unfeeling, loveless, and atheist, is aware of his emotions for the first time.

To understand Joyce properly — and especially his relation to the Church — we must, says Father Power, understand Ireland at that particular moment in history. After the devastation of the Potato Famine, the country rebounded with a nationalist movement, which emphasized Catholic identity — but a kind of Catholicism that looked like Victorian Protestant respectability.

It was a dour hybrid, keen on self-denial and suspicious of pleasure. Father Power refers to this form of religion as “agape without eros” — a devotion that is sacrificial, but joyless.

The Irish Church was also sick with clericalism, a disordered exaltation of the status of priests. According to Father Power, “The clericalist distortion of Christianity” led to “religious aristocratism,” much to the detriment of lay spirituality.

This leads Father Power to make a crucial distinction between anti-Catholicism and anticlericalism. Joyce, he says, “was deeply anticlerical because he disliked the institutional form taken by Catholicism in the Ireland of his youth.” Yet “he remained haunted by the essences of the religion he only seemed to flout.”

When a close friend, a French Catholic named Marie Jolas, took offense at one of Joyce’s remarks, he explained: “Ah, it’s different in France. In Ireland Catholicism is black magic.”

In leaving Ireland, Joyce exiled himself from his native country — yet went on to write about nothing but Dublin. He rejected the Irish Church and yet he was able to express himself only in “Catholic categories.”

Joyce’s brother Stanislaus, an atheist, acknowledged this, saying that James, to the end, “considered Catholic philosophy to be the most coherent attempt to establish … intellectual and material stability.”

In a surprising turn, Father Power identifies a kindred spirit for Joyce in Saint Josemaría Escrivá. The Spanish priest was roughly Joyce’s contemporary, and he shared Joyce’s horror of clericalism as well as his desire to epiphanize the faith in material ways and in ordinary life.

In synthesizing the thought of these two men, Father Power concludes the book by proposing “a Christian aesthetic of the ordinary.” The stunning example of this comes in a climactic scene in Joyce’s “Portrait of the Artist,” when Dedalus is moved to ecstasy by the sight of a young woman playing at the beach:

“He was alone. He was unheeded, happy and near to the wild heart of life. ... Heavenly God! cried Stephen’s soul, in an outburst of profane joy.” For Dedalus, as for St. Josemaría, there is no inherent contradiction between the sacred (“Heavenly God!”) and such pure and “profane joy” experienced in the world.

Joyce’s “Catholic Categories” is not the first book to explore Joyce’s relationship to Catholicism. Hugh Kenner did it in “Dublin’s Joyce.” William T. Noon, SJ, did it in “Joyce and Aquinas.” Kevin Sullivan did it in “Joyce Among the Jesuits.” Mary and Padraic Colum set out to do it in their memoir. Anthony Burgess did it most memorably, though briefly, in his wildly entertaining study “Re Joyce.”

But no one has taken up the task as systematically and thoroughly as Father Power. His book has flaws. It began, as many literary investigations do, as a doctoral dissertation, and it still bears the telltale marks: the cumbersome apparatus, the numbered outline played out in subheads (“III.4.4.2: The End”), and the occasional repetitions and redundancies.

The book’s most glaring fault is its omission of any discussion of “Finnegans Wake,” Joyce’s last novel (if it can be called a novel), which he spent 16 years writing. “Finnegans Wake” is experimental and essentially different from Joyce’s other works; so its omission is understandable, but its absence calls for a word of explanation.

This is, even so, the book that some of us have wanted for decades. It marks Father Power’s debut as an author. I confess I’m eager to buy his next book.