A few years ago, during the darkest days of the Theodore McCarrick scandal, I was talking to a man who had spent some years in prison because of a traffic accident while using drugs.

“Now anything good he did will be forgotten,” I was surprised to hear him say when the subject came up.

The man had sympathy with one who had become a leper. The erstwhile powerbroker and friend of all sorts of important people was officially friendless.

Everyone Knew, it was said, but Everyone Said They Didn’t Know. I find it hard to believe that no one had heard the rumors — I heard them in a little village in El Salvador from a priest from New Jersey who was inclined to gossip.

But by the time the rumors “metastasized,” the churchman’s reputation was covered in stage 4 cancer. He became, as they would say in El Salvador, a piñata. Colleagues and even a few former protégés took their turn with the stick.

The tarring and feathering of the image of Cardinal McCarrick was irresistible because it crossed all kinds of lines and made the whole world kin, like Oscar Wilde’s remark about the cliché. Anti-clerical liberals, many opponents of clerical celibacy, talked about a “culture” that protected clerics to the harm of the faithful. Anti-clerical “conservatives,” who were sick of a Church leadership that seemed always eager to accommodate modernism along with “once over lightly Catholic” politicians, saw a perfect example of why the Church in America is in trouble.

Neither side saw the affaire as the tragedy it was. If there were a Catholic Shakespeare hiding somewhere, they’d have excellent material for a play about a renowned cleric who met his downfall through his compulsive sexual misbehavior.

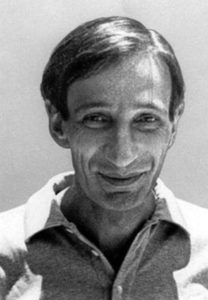

His foil would be his contemporary Ivan Illich. Both he and McCarrick were protégés of Cardinal Francis Spellman, the archbishop of New York during the mid-century. Illich is not as well known but should be: a one-time Catholic priest and controversial social theorist popular during the ’60s and ’70s, he articulated critiques of many of the assumptions that support American culture.

It was Spellman’s passionate concern for the Church in Puerto Rico that launched both Illich and McCarrick’s careers. The former would prove to be the ultimate outsider, the latter the ultimate insider.

McCarrick told me in an interview once that Illich had encouraged him to get his doctorate in sociology when he met him while McCarrick was studying Spanish in Puerto Rico. At the time, Illich was vice rector of the Catholic University of Ponce and director of an institute to which Spellman sent half of his new priests for training in Spanish.

Eventually, McCarrick followed Illich to Puerto Rico. By that time, Illich had been booted out of the island by the bishop of Ponce, an Irishman whose political project of a Catholic party in Puerto Rico was a failure. Illich worked at Fordham for a while and then moved on to Cuernavaca, Mexico, where he founded an institute with a language school to prepare missionaries from Anglo North America to Latin America.

It was ironic that Monsignor McCarrick was made president of the Catholic University of Ponce and director of the institute Illich had founded. Illich, said the cardinal in a private conversation with me, was “a river without banks” or a “motor with no gears,” in short, just the opposite of the super competent bureaucrat McCarrick. Illich, the monsignor with a complicated personal itinerary and vaguely leftist tendencies, became a public intellectual on the outskirts of the Church.

McCarrick’s path was quite different. His was a pragmatic and practical intelligence. After his time in Puerto Rico, he eventually became a kind of aide de camp of Spellman’s successor in New York, Cardinal Terrence Cooke. A few years later, McCarrick was appointed to lead the brand-new diocese of Metuchen in New Jersey, and from there, bounced to become archbishop of Newark and then, apparently as a reward, to Washington, D.C., a cardinalatial see, at the unusually late age of 70.

Even bishops have said that they questioned how a man about whom there were many rumors of ambiguous affections could have risen as he did. Their surprise surprises me. Anyone who ever met McCarrick would have to admit the extraordinary charism of the man for organizing and articulating issues. He is a brilliant talker (a “world class raconteur,” as I described him in a news article years ago), an avid world traveler and polyglot, and an executive par excellence. His promotion of new movements, his Midas touch for Church finances, and his skills as a preacher were all elements of a powerful résumé.

His personal problems and compulsive sexual behavior, which seem to resemble addiction, about which there are some confusing, contradictory reports, somehow did not stop him from being a high-functioning Church-statesman. He led the double life of an addict.

When we studied our first course in moral theology in the seminary, we were instructed to keep separate private morality issues from public morality. A person’s private morality was not to be exposed to others unless absolutely necessary. To expose someone’s private sins was detraction. To invent sins was calumny. Both were wrong. The Vatican’s “McCarrick Report” seemed to me to come awfully close to the sin of detraction, in a supposed effort at transparency, with monsignors recalling the ex-prelate’s inebriated gropings at banquets.

I observed McCarrick up close for a few days when he visited El Salvador for an event commemorating the assassination of the now-St. Oscar Romero. This was after his retirement, before Pope Francis’ election. He prayed his breviary in Italian in the chapel of the residence where he stayed, preached very well in Spanish at a Mass attended by priests and bishops from the whole country, and gave an engaging, inspirational speech to seminarians. As I chauffeured him around San Salvador, I was impressed by the breadth of his experience and the quickness of his assessment of people and situations. I was amused at his introducing me to the staff of the private jet he had borrowed from a friend for the trip. We lived in different worlds.

I pray for the repose of McCarrick’s soul. I also wonder what Illich would have said about his rival’s demise. He died years before his rival, and Illich’s scandals were all intellectual.

The two were a true study in contrasts: the consummate, successful (until he wasn’t) Church politician and the anarchist priest. And what would their old mentor Cardinal Spellman have to say about the fate of his two protégés?

We Americans tend to not pay enough attention to the lessons of history. But McCarrick was involved in so much of American Church history that will be ignored. There will be no catharsis from this narrative of ambition, idealism, talent, energy, and charm that led to nearly absolute humiliation.

Oscar Wilde, writing about his prison experience, observed that the poor tended to say about people in prison that they had got “in trouble,” which he found a more Christian attitude to take. My friend in recovery reacted to the cardinal’s tragedy the same way. However, I expect little reflection about achievement and history and less charity in general.