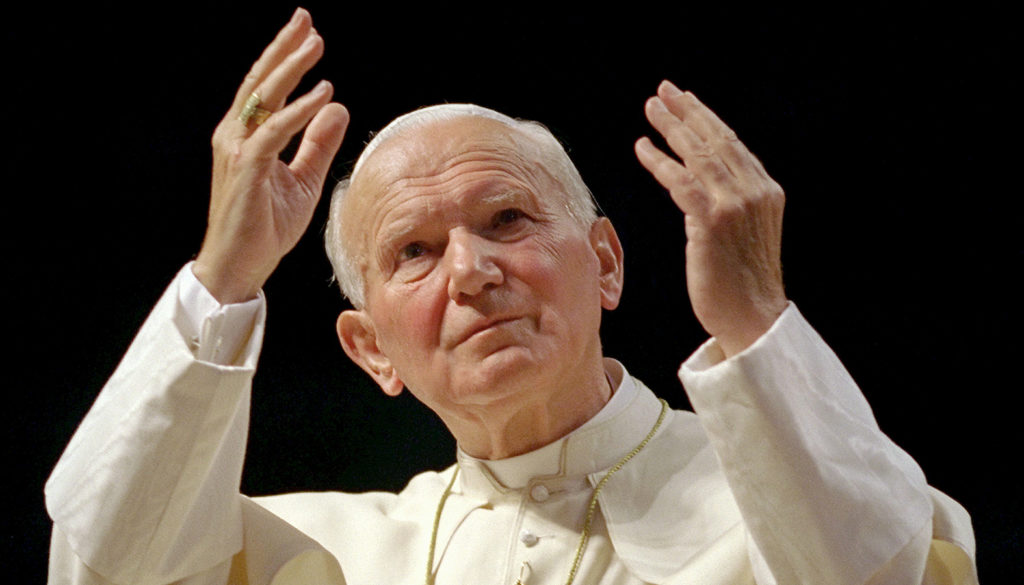

ROME — Twice in the space of a month, St. Pope John Paul II has been at the center of a controversy over his legacy regarding clerical sexual abuse. While the Vatican largely sat out round one, it’s come on strong in the second, including a direct and unusually feisty intervention by Pope Francis himself.

Explaining the difference between the two situations captures a couple of core truths about the Vatican, both of which are important to understanding the place.

Things began a month ago, when a documentary from a Polish television network and a new book came out around the same time, both accusing the future John Paul of mishandling abuse cases while he served as the archbishop of Kraków from 1964 to 1978.

In a March 6 broadcast, the Polish broadcaster TVN identified three abuser priests it claimed John Paul knowingly assigned to other parishes or monasteries. In one case, the network alleged, then-Cardinal Karol Wojtyla wrote a letter of recommendation for a priest to Cardinal Franz König of Vienna, Austria, without mentioning that he’d been accused of molesting minor boys.

The new book, titled “Maxima Culpa: John Paul II Knew,” by Dutch journalist Ekke Overbeek, made similar charges.

Defenders of the late pope note that both the documentary and the book rely in part on the archives of Poland’s Communist-era secret police, which saw the Catholic Church as an enemy and often manufactured charges against clergy as a method of intimidation.

Poland’s governing Law and Justice Party, which depends on Catholic support, rushed to John Paul’s defense, pushing a resolution through the national parliament proclaiming him “the greatest Pole in history.”

While Cardinal Stanislaw Dziwisz, John Paul’s longtime secretary who succeeded him as the archbishop of Kraków, and Bishop Stanislaw Oder, the postulator for John Paul’s sainthood cause, both rejected the charges against the late pope, the Vatican remained largely silent.

Round two began on April 11, when Pietro Orlandi had an eight-hour meeting with the Vatican’s Promoter of Justice, meaning its top prosecutor, an Italian layman named Alessandro Diddi.

Orlandi is the brother of Emanuela Orlandi, the daughter of a Vatican employee whose disappearance in 1983 remains Italy’s most notorious unsolved mystery. Diddi recently announced the opening of an investigation to determine what the Vatican may know about the case, and the meeting with Orlandi was part of that effort.

Immediately afterward, Orlandi went on national television and triggered a firestorm with his comments on John Paul.

Orlandi played a portion of an audio recording of an ex-Roman mobster, who effectively accused John Paul of conniving in a pedophile ring in the Vatican and suggested that Emanuela Orlandi had been killed to cover it up.

Pietro Orlandi added, “They tell me that sometimes Wojtyla would go out at night with two Polish monsignors, and it certainly wasn’t to bless houses.”

In this case, the Vatican’s reaction was swift and sure.

The Vatican’s editorial director, Andrea Tornielli, published an article in the Vatican’s newspaper, L’Osservatore Romano, blasting both the recording and Orlandi’s decision to air it on national television.

“Think what would happen if someone had gone on television to affirm, on the basis of ‘hearsay’ from an anonymous source and without the shred of [evidence] or even a third-hand testimony, that your father or grandfather left the house at night together with some ‘snack buddies’ to harass underage girls?” Tornielli said.

“Evidence? None. Clues? Least of all. Witnesses at least of second or third hand? Not even the shadow. Only anonymous defamatory accusations,” he said.

Calling the episode “madness,” Tornielli wrote that “the defamation must be denounced because it is unworthy of a civilized country to treat any person in this way, living or dead, whether cleric, layman, pope.”

Pope Francis joined the fray on Sunday in his noontime Regina Coeli address.

“Certain of interpreting the sentiments of faithful from all over the world, I direct a grateful thought to the memory of St. John Paul II, who in recent days has been the object of offensive and unfounded allegations,” Francis said.

Why the radio silence in the first case, and the full-court press in the second?

First of all, the second controversy arose in Italy, which is the Vatican’s natural habitat. For all its pretense to sovereignty and internationalization, the Vatican remains an inextricably Italian operation: Whatever happens in Italy exercises a disproportionate impact on the perspectives and priorities of Vatican personnel.

That’s especially so in the case of Francis, whose grandparents come from the Italian region of Piedmont and who recently acknowledged that he’s a faithful reader of the Roman newspaper Il Messaggero.

When a pope’s memory is being maligned in another country and language, it just doesn’t have the same in-your-face impact for most Vatican personnel as it does when it’s Italy.

Second, the reactions also betray differing senses of how seriously to take the allegations.

In the case of Orlandi and the Roman mobster, the calculation appears to be that the suggestions are so outlandish, so beyond the pale, that there’s little risk a strong public denial will come back to haunt whoever issues it.

In the case of the documentary and the book, on the other hand, the charges probably strike many Vatican officials as more within the bounds of plausibility. It’s well established that the time in which Wojtyla was in charge in Kraków, the mid-1960s to the late 1970s, coincided with a statistical peak in reported incidents of clerical abuse, so it stands to reason there would have been cases on the future pope’s watch.

It’s also well established that most diocesan bishops of that era handled accusations in the manner described in the reports, i.e., quietly reassigning clergy rather than imposing formal discipline. A priori, there’s no special reason to believe Wojtyla would have acted any differently than the vast majority of his colleagues.

Given all that, Vatican personnel likely are waiting for the judgments of historians and researchers before wading into the debate, worrying that any public statement in advance of the facts could backfire.

The takeaway is that in the Vatican, silence doesn’t necessarily signify consent, but it often does become a concern.

These two insights — the overweening importance of Italy, and how noise levels correlate with perceived risk — obviously have relevance well beyond the debates over John Paul. Recent experience suggests, however, that the late pope’s memory may continue to be an arena in which their impact is especially keenly felt.