When I was an evangelical pastor, many of my colleagues were preoccupied with the “end times.” The airwaves were alive with preachers predicting Jesus’ imminent return. And bestselling books gave dates to mark on your calendar. The Greek word parousia entered the vocabulary of ordinary English-speaking Christians.

Christians have always used parousia to denote the coming of Christ, with all its attendant events, such as judgment and the renewal of the world.

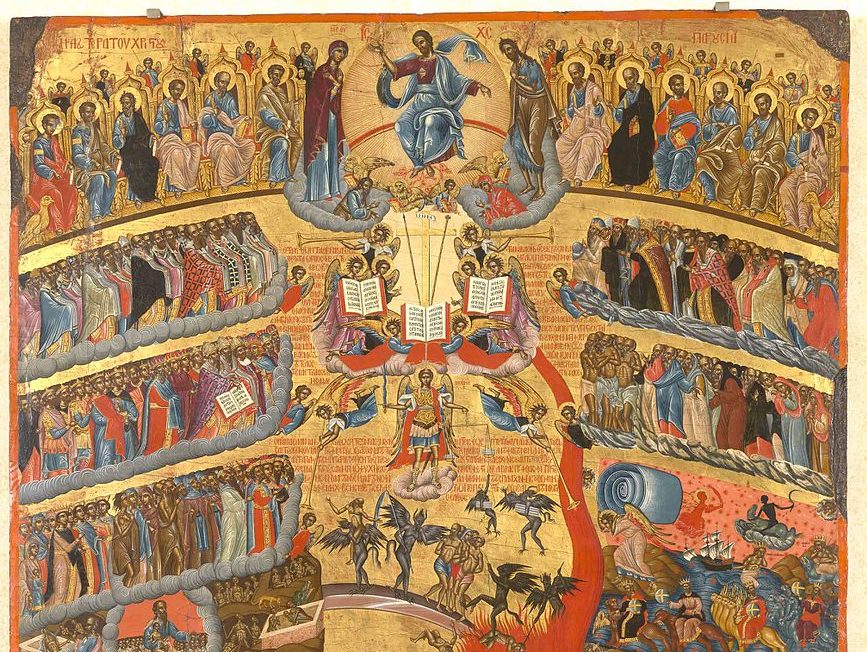

In popular Christian parlance, though, it has come to mean, specifically, Christ’s return in glory at the end of time. Jesus himself used the term to describe that eschatological moment: “as the lightning comes from the east and shines as far as the west, so will be the coming [parousia] of the Son of man.”

But parousia did not always refer to spectacular future events. In the New Testament — in most instances — parousia meant something simple and ordinary.

For example, when St. Paul spoke of his own parousia, he gave it a self-deprecating cast. In Second Corinthians 10:10, he’s talking about his critics, and he says: “For they say, ‘His letters are weighty and strong, but his bodily presence is weak.’ ” In that sentence, the translators render parousia as Paul’s “bodily presence,” which is unimpressive. Paul uses the word in the same way in his Letter to the Philippians (2:12).

Jesus may have intended the same humble connotations.

None of this rules out a parousia of Christ at the end of history. Theologians call that “coming” of Christ the “final advent” or “plenary parousia” — not because Christ will have a greater fullness, but because humankind will be able to behold him in his fullness.

Since Jesus’ first coming, he is present in the world in a way that he was not during the old covenant. Yet he remains veiled in a way that he will not be veiled at the consummation of history.

In his incarnation, Jesus came; and, as he passed from human sight, he promised to sustain his presence forever: “I am with you always, to the close of the age.” Thus, his parousia — his presence — remained with Christians even as they prayed for its plenitude.

The scholar Jaroslav Pelikan observed that in the early Church, “The coming of Christ was ‘already’ and ‘not yet’: he had come already — in the incarnation, and on the basis of the incarnation would come in the Eucharist; he had come already in the Eucharist, and would come at the last in the new cup that he would drink with them in his Father’s kingdom.” The Mass was “a way of celebrating the presence of one who had promised to return.”

What the ancients saw in the liturgy was the coming of Christ: the parousia; and what they meant by parousia is what Catholic theology came to express as the “real presence” of Jesus Christ.

The parousia is what the Church celebrates at every Mass and in every act of Eucharistic adoration — and on the feast of Corpus Christi, which this year falls on Sunday, June 2, in the United States.