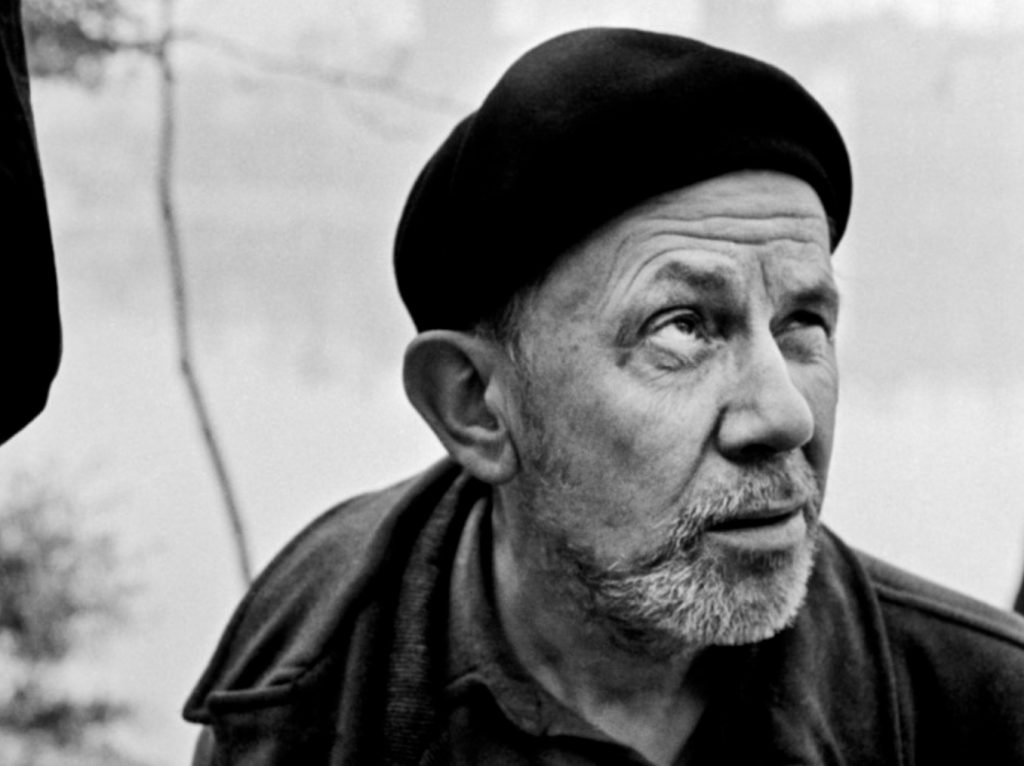

Josef Sudek (1896-1976), known as “The Poet of Prague,” lost his right arm in World War I and in the course of a 65-year vocation, wandered the streets of his beloved hometown, taking evocative photographs of cathedrals, deserted squares, and his own gloriously cluttered studio apartment.

“Josef Sudek, Poet of Prague: A Photographer’s Life” (1990), by Anna Fárová, tells much of the story. Born in Prague, Czechoslovakia, Sudek began experimenting with a simple box camera in his late teens.

Of the incident during World War I that marked his life, he wrote: “I lost my arm during the eleventh offensive … as we charged our own artillery started shelling us from the back … I felt as if a rock hit me in the right shoulder. I started looking around but all the guys who had been standing were now dead. I crawled back to our own lines, and as I was getting into a dugout, I slipped and it started to hurt. Then I lost consciousness.”

After several unsuccessful operations, doctors were forced to amputate. Fárová notes: “It is easy to speculate, impossible to know how wounding the loss was to his psyche, its effect upon his art and sense of his physical self. He is not known to have had any romantic attachments in his life, he never married.”

Back in Prague, he was accepted to the newly established School of Graphic Arts. He graduated in 1924, with a solid grounding both in technique and the economic business of photography.

Nonetheless, his views were controversial. He claimed, for example, never to use a light meter, and insisted that photography cannot be an art “because it is dependent on things that exist without it and apart from it, i.e., the world around us.”

But what a world. And how beautifully, carefully, and lovingly Sudek proceeded to record it. “Luminous,” “mysterious,” “haunting,” “ethereal,” “otherworldly,” “timeless,” and “romantic” are a few of the words regularly applied to his work.

He began contributing his work internationally, traveling, and even achieving a certain level of fame.

But in 1926, the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra invited him to accompany them on tour. Traveling down the Italian boot, he later wrote, “One day we came to that place — I had to disappear in the middle of a concert; in the dark I got lost but I had to search. Far outside the city toward dawn, in the fields bathed by the morning dew, I finally found the place. But my arm wasn’t there — only the poor peasant farmhouse was still standing in its place. They had brought me into it that day when I was shot in the right arm. They could never put it together again.”

He had longed to find his lost arm, and he couldn’t. He disappeared for two months: no-one ever knew where, though his worried family and friends called the police. He surfaced at last in Prague. “From that time,” he reported much later, “I never went anywhere anymore and I never will.”

He would never go anywhere else and yet in Prague he had found his vocation and his destiny.

He rented a small studio at the back of an old tenement house at the base of Petřín Hill, which he crammed with records, paintings, statues, and drawings, and where he would live for the next 30 years.

His personality was strong, brusque, and in many ways contradictory. He mercilessly haggled with creditors, tax boards, and patrons, often falsely crying poverty. He also supported his mother and sister and often gave away extravagant sums of money to friends, charities, and the poor.

His patience was legendary. He sometimes waited weeks or months to print a negative and took four years, from 1924 to 1928, to produce a 15-photo album of St. Vitus Cathedral: “a whole realm of light and shadow,” as he described it.

At his studio, described by one friend as “a phantasmagoric mess,” Sudek had friends in for nights of classical music curated from his gramophone record collection, gazed through rain-streaked windows into his tiny garden, and composed still lives: a single pear on a ridged white plate, a white rose in a thick-stemmed drinking glass, a broken eggshell on the windowsill ledge.

In 1940, he discovered contact prints and began lugging around a heavy camera, propping it on his lap and sometimes using his teeth to help operate it. He published a collection called “Prague Panoramas.” His subjects included crumbling estates, cemeteries, gardens, statuary. Cobblestoned squares, slick with rain, at twilight. Blurred figures, in topcoats and hats, huddled beneath a tree in conversation. Secret, snow-drifted eaves visible only to birds. Carriage lamps at dusk. Streetlights strung like a necklace along the river.

He moved at last to another studio (now open to the public as a museum), a former jeweler’s shop where he lived out his years, dying at 80 and leaving 16 books of photographs.

“What would I be looking for when I didn’t find what I wanted to find?” he once wrote of his work.

What we are all looking for: our truest, whole selves, lost in the Garden of Eden. And to be found again — after the Resurrection.