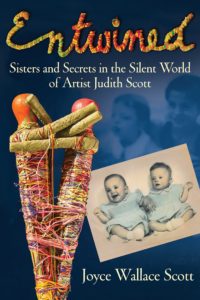

Judith Scott (1943–2005), American fiber sculptor, was born in Columbus, Ohio, with Down syndrome. Her twin sister, Joyce, tells their joint story in the memoir “Entwined: Sisters and Secrets in the Silent World of Artist Judith Scott” (Beacon Press, $21.04).

For their first several years, the two were inseparable, playing in their backyard sandbox, collecting pebbles and leaves. But in those days, children with developmental disabilities — and their families — were stigmatized and often shunned.

One day Joyce woke, and Judith was gone, spirited away by her parents to a “home.” Unknown to her family, Judith was also deaf, a fact they did not learn until she had been institutionalized for many years.

Meanwhile Joyce had a child out of wedlock, gave her baby daughter up for adoption, moved to the Bay Area, and with John, the partner she would eventually marry, had two more daughters. Still, her beloved twin was never far from her mind and heart. She sent packages, visited from time to time, and wrote letters.

But she was shocked to hear, for example, that at one point all of Judith’s teeth had been pulled: easier not to have to deal with cavities, reasoned the institution.

In the mid-1980s, Joyce attended a silent retreat in the mountains near Santa Cruz. The event was transformative. She returned home with the unshakeable conviction that Judith must come to live with her.

She consulted a lawyer, acquired guardianship, and arranged for Judith to be flown from Illinois to California. Judith quickly and happily settled in. Before retiring each night, she placed her purse and a stack of her treasured magazines — she liked the colors, shapes, and glossy paper — beneath her pillow.

In 1987, Judith was enrolled at the Creative Growth Art Center in Oakland, which supports people with developmental disabilities. For two years, Judith sat silently, apart from the others, surrounded by art supplies for which she seemed to have little use.

But one day a visiting fiber artist came to the Center and taught a class. Judith watched. In the ensuing days she began collecting a few seemingly random objects and began wrapping and tying them off with foraged yarn, thread, and string. The first piece she produced is clearly a pair of twinned figures, tenderly embracing.

Judith Scott had found her voice, her passion, and her vocation.

For the next 18 years, she went to the center each day and worked steadily from 9 to 3, breaking only for lunch. Undistracted by noise — a side benefit of her deafness — she descended into a world of her own.

Though unable to talk — “Ho ho bah” was a favorite ejaculation — Judith had an uncanny sense of presence and purpose. She knew exactly how to make her desires known. Woe to anyone who tried to trespass upon her precious magazines. She became the undisputed Queen Bee of the Creative Art Center, unswerving in her focus.

Stooped, shrunken, with dark circles around her eyes, Judith came to love headgear: a fringed scarf tied around her forehead, turbans. She took to festooning herself with costume jewelry: multiple strands of beads, chunky bracelets.

She came to favor strips of fabric for wrapping. Her deeply-controlled structures had the air of totems or mummies, often with strange protuberances. Always, something was buried within the piece. It might be a Styrofoam cube, a piece of wood, or an industrial spool. It might be a shopping cart or once, someone’s paycheck.

The art world started to take notice — but Judith was unimpressed by the star-studded gallery openings. She might walk around, throw kisses toward one or two of her pieces, then sit down in a corner and demand to be taken home.

Her work is now in museum collections around the world: New York, San Francisco, Dublin, Lausanne, Tokyo.

When her time came, Judith lay down beside Joyce, looked deep into her sister’s eyes, and abruptly stopped breathing.

Who was she, really? Joyce mused afterward. What could she have been trying to say? Did those straitjacketed, swaddled structures represent the trauma of 35 years of institutionalization? Were they meant to telegraph that no matter how deeply the world tries to bury the human spirit, it will rise triumphant and exuberant? Were they notes of a kind of music heard by Judith alone, in her lifelong silence and exile?

We’ll never know, but one thing is certain. They were the product of a profound intelligence; of a being ordered in some mysterious, single-minded way to the rules of an unseen realm.

“I had wondered … if she were not a kind of healer,” said Joyce. “A teacher, taking a vow of silence, willing to take on enormous suffering in order to be with us in a place of love and wisdom.”

The Judith Scott story illustrates the power of art. It highlights the explosive potential and infinite worth of every human being. And in large part, it demonstrates the incredible strength of a sister’s love. Could Judith possibly have flowered as she did without Joyce’s unstinting efforts, patience, and support?

“Outsider,” a 26-minute documentary about Judith Scott’s life and art, is available for rental on vimeo and for DVD purchase at Icarus Films.