For all you ink aficionados, through April 15 the Natural History Museum is featuring a special exhibit: “Tattoo.”

Tattoo culture has been 5,000 years in the making. Since the 20th century, L.A. has formed a significant part of it.

“Before it becomes a mark,” the museum notes, “a tattoo is process. Its results can be a sign of identity, a rite of passage, a type of protection, a form of medicine, a memory made visible, or a piece of art to be collected and worn on that most intimate of canvases, the human skin.”

The exhibit, which costs 11 bucks in addition to the entrance fee, features commentary on the wide and varied history of tattoo, vintage photos, flash sheets of pinup girls, dragons and Catholic iconography, and videos.

Silicone arms, tattooed in various styles and backlit like medieval manuscripts, are displayed throughout in glass vitrines. There are tribal designs; a giant, writhing octopus by Kari Barba (b. 1960), whose Long Beach shop occupies the site of the legendary Bert Grimm’s World Famous Tattoo; and my own personal favorite, a style honed by Montreal tattoo artist Yann Black (b. 1973) that he describes as “somewhere between German Expressionism and Russian Constructivism.”

Tattoos have flourished among indigenous cultures for millennia. The “World Heritage” section features tattoos from China, Taiwan, Polynesia, Africa’s Congo Basin, New Guinea and Borneo. In New Zealand’s Maori culture, “tools similar to sculptor’s chisels were used to cut channels in the skin, into which pigment was added.” Ouch.

Needles have been fashioned from cactus spines, citrus thorns and Bic pens. Thomas Edison invented an electric stencil pen, and the Burmese made ink from the cremated remains of monks and the bile from an enemy’s liver.

Women, as both tattooers and tattooees, are no slouches in the tattoo department.

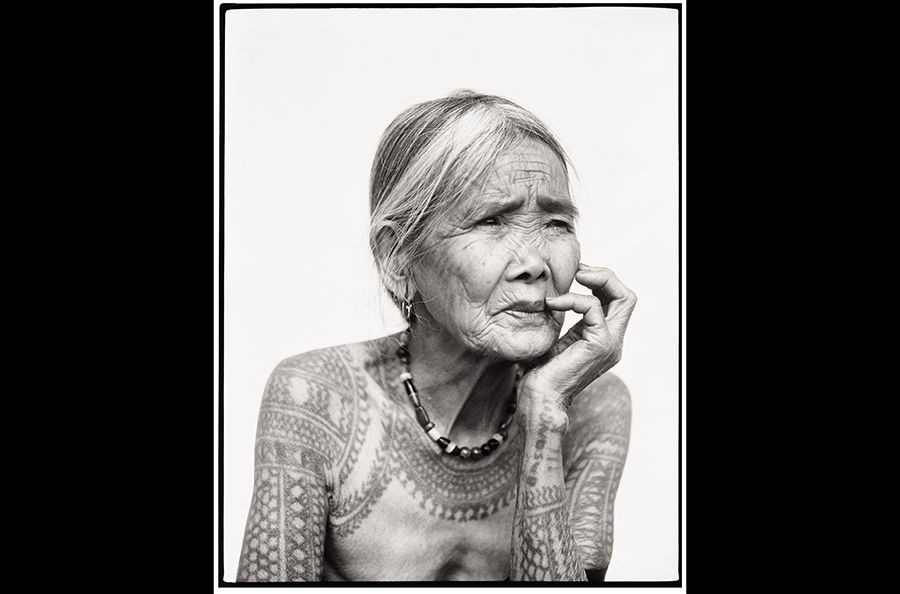

Whang Od, 92, for example, is from the rural Philippines. “I am a tattoo maker because I am poor,” she says, as pigs root around the dirt floor of her workshop. People come from around the world for her tattoos, which are gorgeous, and I badly wanted to tell her she should charge more for them. The white guy she was pounding needles into looked like he was about to pass out from pain, and a little palm wine, I felt, might also have been in order.

Long Beach, home of the U.S. Navy’s Seventh Fleet, was a hub for sailors, bikers and low-riders during the ’50s, ’60s and ’70s. In the section “Los Angeles: Local Goes Global,” a video features old-school guys from the Long Beach Pike, in its heyday one of the tattoo capitals of the world.

These keepers of the flame are a fount of tradition, history and stories, and deeply proud of their contribution to this chapter of L.A. culture.

Another section, “Los Angeles Black and Gray,” covers the popular tattoo phenomenon — fine line, single needles, guitar string — that originated in East L.A. Says Big Gus of Collective Ink Gallery, “Black and gray came out of my backyard, from the streets of L.A. It came from prison tattoos. It came from the homeboys in the neighborhood.”

The Virgin of Guadalupe, Jesus in Agony and the “Smile Now, Cry Later” motifs are popular. As Edward “Chuco” Caballero (1952-2008), a “walking canvas” of black and gray, observed, “I grew up in the ’60s, when you could own a tattoo only if you were a gang member, a drug addict or in prison. Now, celebrities and movie stars have made tattooing mainstream.”

There’s nothing wrong with the idea that a tattoo is a possession to be owned and a right to be earned. The whole allure, if any, to my mind lies in the outlaw aspect, the tribalism.

Still, the insularity of tattoo culture can work both ways. It’s one thing to choose to mark yourself as an outsider; it’s a very different matter to be marked as one by others. Two of the exhibit’s most moving images appear in a section about those upon whom tattoos have been imposed.

One is of an Armenian woman with haunted eyes who had been forced into prostitution during the genocide, and whose face and arms were tattooed by her Turkish captors. The other is of Aljoscha Lebedew, a young boy, also with a thousand-yard stare, who at Auschwitz had been tattooed on his left arm, as all inmates were, with an ID number.

Left unexplored is possibly tattoo’s most intriguing aspect: the element of pain. Personally, I just can’t warm to the words “hammer” or “chisel” in the same sentence as the phrase “human flesh.” Clearly, many can — and the images of so many bodies virtually covered with tattoos makes me wonder if the willingness to suffer as a badge of honor can segue into an actual addiction to pain.

I toyed for a time with the idea of getting a tattoo: the Sacred Heart of Jesus, wrapped with thorns and engulfed in flames, I thought, might be nice. But on further consideration, I prefer to leave this world the way I came in.

Besides, life brings quite enough suffering as it is.

Heather King is a blogger, speaker and the author of several books.