“All the Beauty in the World: A Museum Guard’s Adventures in Life, Loss and Art” (Simon & Schuster, $27.99) is Patrick Bringley’s best-selling memoir about the decade he spent working at New York City’s Metropolitan Museum of Art.

When the book begins, his beloved older brother has just died. Into the narrative Bringley weaves his grief, his wonder, his wide-ranging curiosity about art. The tone is hopeful, wryly self-reflective, and human in its widest range.

Bringley is well-educated, a voracious reader, and an indefatigable researcher.

Far from considering the work of a museum guard beneath him, however, he considers his job at the Met a great honor.

We meet Johnny Buttons, the wise-cracking Korean War vet and tailor who fixes the guards’ uniforms.

We learn how the 500-plus guards are assigned, and that they pray for the galleries with wooden as opposed to marble floors (easier on the feet).

We peek into the locker room, the dispatch office, the command center.

Bringley goes out for beers when his shift ends and makes a few lifelong friends.

Meanwhile he gives us a meandering tour of the museum: the old Masters, Medieval Modern, Greek and Modern, Asian. He pores over and reflects on the art with which he’s surrounded.

He develops a deep affection for the museum’s visitors: The ones who inevitably ask, “Where’s the Mona Lisa” (answer: The Louvre) or, of the artifacts in the Egyptian wing, “Are they, you know, real?” or, at least once a day, something to the effect of “Water lilies? Sunflowers? Anything impressionistic?”

Over the course of his employment, he gets married and he and his wife have a son, then a daughter. His outlook upon life and his place at the Met gradually shifts, widens.

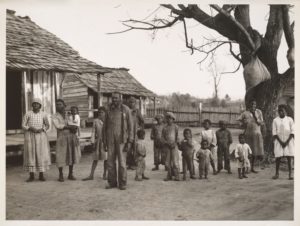

There’s a wonderful chapter, called “Days’ Work,” on the drawings of Michelangelo and the Gee’s Bend quilters from rural Alabama, specifically Loretta Pettway who, like Michelangelo, found her work almost unbearably burdensome and did not especially enjoy it. And made quilts that were almost preternaturally beautiful.

Painting the Sistine Chapel, Michelangelo worked in small, irregularly shaped areas — each would be a “giornata”: Italian for “day’s work.” His drawings show his painstaking, obsessive, pushing-the-boundaries labor.

He complained about “the state of his spine, his buttocks, his paint-splattered face, and his brain in the ‘casket’ of his head.” “I am no painter,” he expostulated at one point. “I waste my time without result … God help me!”

He was appointed in his 70s “to his intense dismay and completely against his will” as the supreme architect of St. Peter’s in Rome. He toiled at it for the last 17 years of his life.

As for Loretta Pettway (b. 1942), “I never had a child life,” she observed. Her husband was an abusive alcoholic and gambler and she started sewing quilts not as an art project, but rather to keep her children warm in winter.

She suffered from insomnia and depression. She didn’t make friends easily. And the bold originality and sheer splendor of one of her quilts, “Lazy Gal Bars,” takes Bringley’s breath away.

For all their differences, he observes, both Michelangelo and the Gee’s Bend quilters “are alike in how they challenge my understanding of art, the making of art, and really the making of anything worthwhile in a world that so often resists our efforts.”

Over time, Bringley settles upon his favorite pieces: an ivory pendant mask of Idia, queen mother of the kingdom of Benin, carved from a thin slice of elephant tusk in the early 16th century. “The Harvesters” (1565), by Peter Bruegel the Elder. The Simonetti carpet, likely produced in Egypt under the Mamluk dynasty around 1500.

But after a decade at the Met, surrounded by some of the world’s finest art, he decides his very favorite piece is a crucifixion by 15th-century Italian friar Fra Angelico.

He likes “the look of tempera paint on heavy wood panels and cracking gold leaf with its red clay base peeking through.” The painting’s “luminous sadness” reminds him of his late brother Tom.

What he likes best, though, is the rabble of onlookers at the base of the cross to which Christ is nailed, “their faces betraying a wonderful range of responses and emotions. Some are solemn, some curious, some bored, some preoccupied.”

“I take this crowded middle of the picture to represent the muddle of everyday life: detailed, incoherent, sometimes dull, sometimes gorgeous. No matter how arresting a moment or how sublime the basic mysteries are, a complicated world keeps spinning. We have our lives to lead and they keep us busy.”

We keep busy. We do the work, doggedly, stubbornly, and grumble afterward, mostly to ourselves. Not so much that we’re called to do the work, which is always an obscure joy, but that we do it so badly, so laboriously. That so much of us is used up in the doing.

But in the end, whether we’re museum guards, artists, parents, field hands, or CEOs, the operative point isn’t the suffering, the isolation, the hard work, the ongoing sense of one’s terrible insufficiency. The operative point is the mysterious, unquenchable life force that keeps us at our painting scaffold, or quilting table, or watch anyway.

Meanwhile it’s all there, right in front of us, every humble minute of every day, Bringley seems to be saying: all the beauty in the world.