It used to be the practice of Pope Pius IX to wander off by himself through the endless corridors of the Vatican Museum and Art Gallery. One day he came upon a group of tourists looking intently at some paintings by Murillo.

“Do you like them,” the pontiff asked. Everyone nodded, but no one spoke. “Well,” said Pio Nono, “How would you like for the Holy Father to show you the most valued of all the treasures here in the Vatican?”

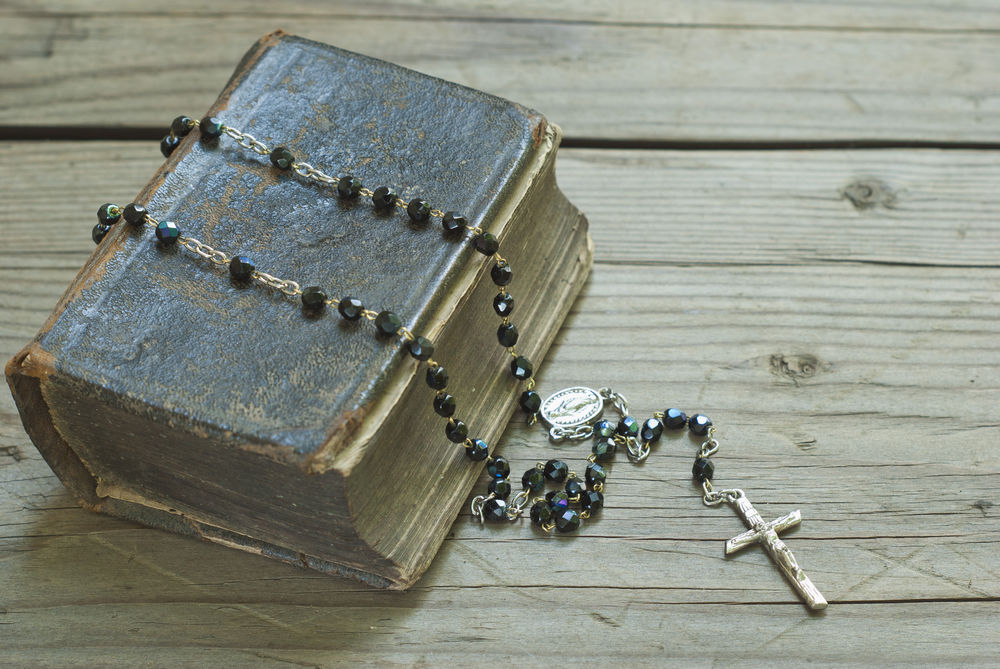

To that question, they all shouted back a hearty “yes.” Then the pope slowly opened his palm to reveal a simple little black rosary, its beads worn from years of use. “There it is,” he said, “a treasure which means more to the Church than all the others combined.”

Those who look upon the Acts of the Apostles as the earliest history of the Church would surely regard the fifteen decades of Our Lady’s Rosary as the “second oldest” and most accurate record of God’s relationship with His People.

Stamped with the seal of centuries, ladened with the richest of indulgences and recommended by all the spiritual writers, the Rosary resembles a portable chapel, wherein the human family maintains unbroken contact with heaven — irrespective of time, place or condition.

So it is that in times of Sorrow, the distressed client of Mary counts off the beads much the same as Christ numbered the cobblestones along the way to Calvary. In times of Temptation, the besieged Christian recalls how the youthful David overcame the giant Goliath with a handmade sling and a fistful of rocks. In times of Stress, the troubled believer ponders the effects of the Rosary as it passed through the chemically-stained fingers of Louis Pasteur, the ink-darkened hands of Joyce Kilmer and the drink infested grasp of Matt Talbot.

The Rosary cuts across the whole gambit of salvation history. No other prayer in all of Christendom embraces a wider or more expressive array of God’s relation with His People.

The Joyful mysteries encompass the announcement of humankind’s salvation, the concern of Our Lady for her kinfolk, the coming of Christ to His People, the presentation of the Messias in the Temple and the appearance of the Christ-child before the Elders.

The Sorrowful mysteries recall the agony of Jesus in the Garden, the scourging of Our Lord at the pillar, the Savior’s crowning with thorns, the carrying of the burdensome Cross and the death of Christ for humankind’s salvation.

The Glorious mysteries relate the triumph of Our Lord over death, the return of the Savior to His Father, the descent of the Holy Spirit, the bodily-Assumption of Mary into heaven and her coronation as Queen.

What other devotion so graphically unfolds the drama of salvation within the framework of daily prayer? The Rosary, the culminated exclamation of belief and hope, is history and prophecy: it is history insofar as it tells what has been and it is prophecy because it foretells what will be.

The Rosary combines the story of the past, the challenge of the present and the promises of the future into a single montage of Christian life.

For every believer, the Rosary should never be further than a pocket’s length away. The Christian may go to bed hungry, cold or ill, but never before reciting the beautiful and relevant “Psalter of Mary.”