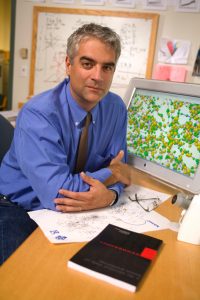

Reading about pandemics in the midst of a pandemic may seem an exercise in masochism, but I would highly recommend one book: “Apollo’s Arrow: The Profound and Enduring impact of the Coronavirus on the Way We Live” (Little, Brown Spark, $29). Written by Nicholas Christakis, a physician and sociologist, he brings to the discussion of COVID-19 a scientific mind allied with an eye for social and historical context.

Christakis finished his manuscript in the summer of 2020, I’m guessing, yet he makes solid predictions about the spread of the disease and does not offer false hope of a quick solution or a miraculous disappearance.

What he provides instead is both background and context. Pandemics are nearly as old as mankind. He lards his book with historical accounts of previous plagues, and he makes it clear that viruses and the pandemics they can cause are an enduring threat to our species. Despite the success in the last century of vaccines defeating such diseases as smallpox, polio and — until recently — measles, the threat of viral assailants will never be eradicated.

Though most of us may have been surprised by the arrival of the worst pandemic (so far) of our lifetimes, epidemiologists were not.

Nor are historians surprised by many of our reactions to this crisis. Today we blame the Chinese (and of course they blame us). In Italy, people were avoiding Chinese restaurants when the coronavirus first made its appearance there, and at one point early in the pandemic, 38% of U.S. beer drinkers said they would not drink Corona “under any circumstances.” There have been reports of verbal and other assaults on Asian Americans linked to anger about the virus.

All of which is better than what took place in the Middle Ages during the bubonic plague. In Strasbourg in 1349, 1,000 Jews were buried alive because they were seen as responsible for the disease. In Milan in 1630, four Spaniards blamed for the disease were tortured, maimed, and then burned at the stake.

Our pandemic instincts are perhaps less homicidal today, but the human desire to blame anything other than the virus itself is still around.

Likewise, our desire to wish it away, a particular failing of politicians. In some states, legislators are behaving as if they can simply decree the pandemic over, even wanting to restrict steps taken to minimize its spread.

Such self-defeating ignorance is nothing new to our species. In the last bubonic plague outbreak in Europe in 1720, a doctor wrote: “Already the public, prone to delude themselves, and easy to believe what they wish to be true, attributed to malady of these persons to anything rather than to the plague, and began even to joke upon their own alarms. But the subtle destroyer, mocking alike the precautions of the wise and the jokes of the incredulous was secretly insinuating itself far and wide.”

Such accounts call to mind the experience of nurses today who recount holding the hands of the dying who still doubted that COVID-19 was real.

And while Americans ran after hoax therapies, that too is predictable. In the plague of Justinian in the sixth century, people started throwing pitchers out their windows in the belief that the noise would scare death away. A witness said that for three days the city rang with the sounds of breaking pottery.

For Christakis, our symptoms of pandemic avoidance are clear: “The lack of scientific literacy, capacity for nuance, and honest leadership has hurt us.”

We are fortunate, even in our ignorance, however. We have drugs that can moderate the symptoms. We have vaccines produced in record time that should — unless severe mutations outrace our rush to herd immunity — eventually protect us. The truth is that masks and social distancing have historically saved many lives as viruses rapidly circulate.

Despite how terrible our death toll is today (450,000 and counting in our first year), if not for the preventative actions we’ve taken, it would have been much higher. The Spanish Flu killed 550,000 Americans (the equivalent of 1,721,000 deaths today).

Yet our life expectancy is falling and our inability to resolutely respond as a community to this grave threat portends a long denouement before we feel safe once more.

Christakis says history suggests that when we get the genuine “all clear,” “consumption will come back with a vengeance.” He quotes an observer in 1348: When the plague subsided, “all who survived gave themselves over to pleasures: monks, priests, nuns, and lay men and women all enjoyed themselves. ... And everyone thought himself rich because he had escaped. ...”

Pope Francis has urged us again and again to see in this crisis an opportunity to renew our society, to reach out to our fellows, to renounce our false securities. What will it be: Roaring ’20s or a reformation of society for the common good?

Unfortunately, if history holds, that answer may be predictable as well.