Charles Lummis’ California home echoes the ‘noises’ of a man larger than life

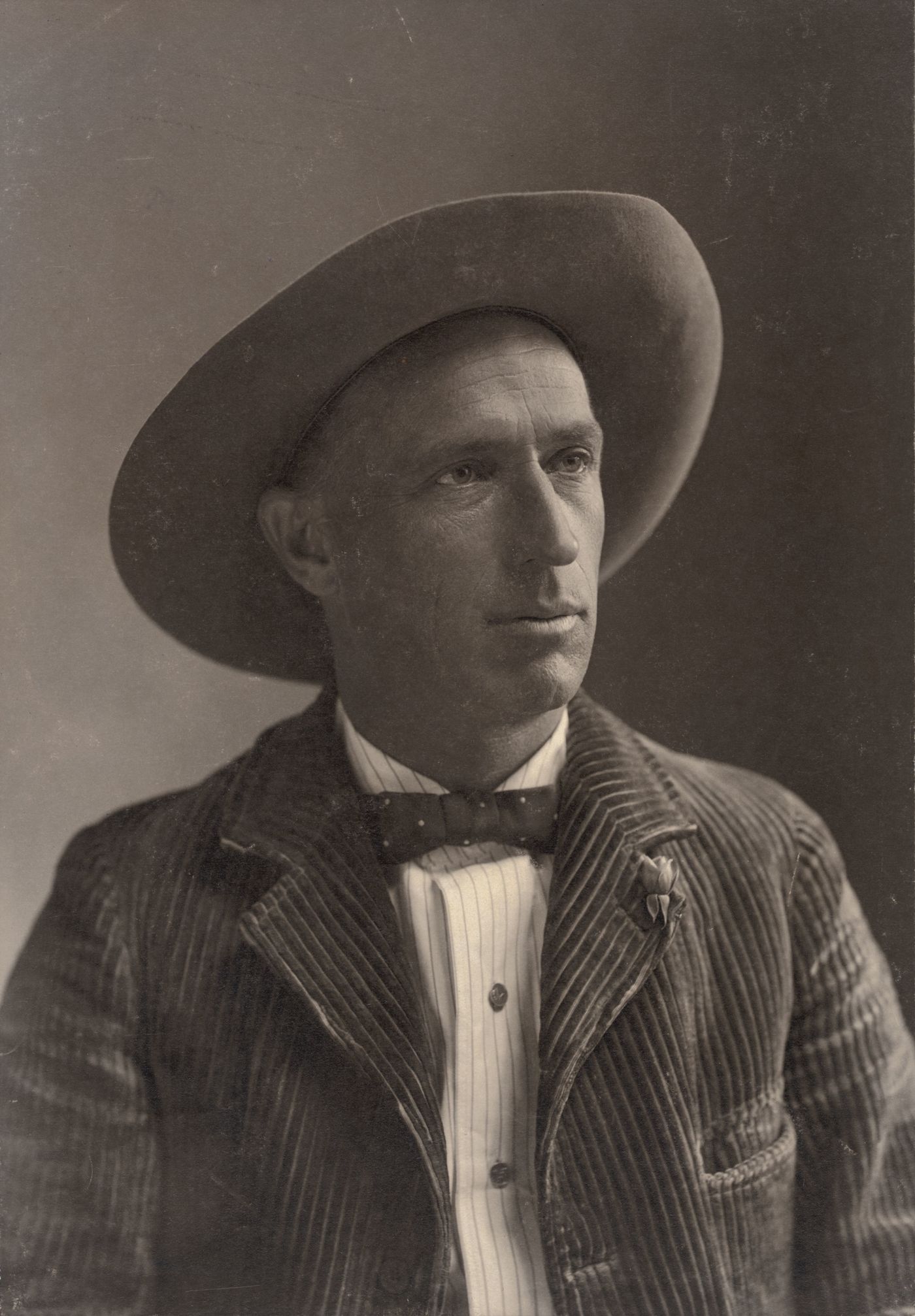

Charles F. Lummis (1859-1928) was a complicated figure.

Born and raised in Lynn, Massachusetts, in 1884, Lummis made national headlines by walking 3,507 miles from Cincinnati to Los Angeles in order to take a job at the “LA Times.”

He broke his arm en route and set it himself — then completed the rest of what he called his “tramp.”

Upon his arrival, the fledgling newspaper offered him the new position of city editor. Over time, he became a lover of all things Californian. He served from 1905 to 1910 as city librarian, and founded LA’s Southwest Museum.

He helped save four California missions. He also championed indigenous cultures, living for a time among the pueblos in New Mexico, and traveling to Mexico, Bolivia and Peru.

He was charismatic, a self-taught polyglot, journalist, photographer and historian, a spinner of tales who gathered acolytes around him to execute his feverishly ceaseless orders, projects and plans. An obsessively hard worker, he claimed to get by on two or three hours of sleep per night.

He wore a suit of parrot-green corduroy, wound a length of Mexican-red cloth around his waist and completed the outfit with a soiled Stetson hat.

rn

rn

rn

He designed and largely built himself the iconic home known as El Alisal — the local Spanish name for “Place of the Sycamore.” Located at 200 E. Avenue 43, in what is now LA’s Highland Park neighborhood, the 4,000-square-foot rustic American Craftsman was constructed principally from stones and granite boulders gathered from the nearby Arroyo Seco.

Begun in 1897, the home, with its round castle turret, lattice-work chimneys and hand-hewn beams, took 13 years to complete to Lummis’ relative satisfaction.

El Alisal featured a front door, consisting of two halves, each weighing 1,000 pounds, and a zaguán (entryway). When his son Amado died at the age of 6 from pneumonia, Lummis had the body carried out through the zaguán, closed the doors and never opened them again.

The comedor (dining room) was modeled after the kitchen at Mission San Juan Capistrano, where the early priests had cooked over an open fire.

The 28-by-16 museo (museum) served as a gallery for Lummis’ collection of Native American rugs, baskets, blankets and pottery. Its distinctive “photograph window” was lined with glass plates from his travels.

It was also the room where Lummis liked to entertain. He threw what he called “noises” — raucous gatherings of bohemian artists, writers and musicians at which he relished holding court.

But for all his civic fervor and his bonhomie, he was also, some said, an alcoholic, a liar and a lecher. Married three times, he fathered several children. One, Bertha, had been conceived during Lummis’ stint as a youth at a New Hampshire resort hotel. When Bertha appeared in his life as an adult, he insisted that she come West and rather ostentatiously installed her alongside his then-wife and other children at El Alisal.

His daughter Turbesé, and Jordan, a son, went on to publish the book “Charles F. Lummis: The Man and His West.”

Though the tone is largely hagiographical, the two also wrote, “But the man who found such warm enjoyment of these parties and the host who celebrated fiesta days at El Alisal was different from the silent man his children usually knew.

“Lummis labored to make a home for them such as few possessed; he won the love of hundreds. But the spontaneous affection they might have felt for their father was discouraged by the New England silence which often hid his love.

“His feudal ideas and the switch he wielded to make his children what he thought they ought to be kept them from knowing him as he really was.”

By the time he was 49, they observed, he felt himself to be old. “The pressures under which Lummis lived, the incredible hours he worked, the strenuous emotions, alcohol, battles against hostile associates and five to ten cigars a day, all were taking their toll. … The only thing to do was to take more strong coffee or a sip of apricot brandy or a glass of ‘jusque’ and work a little harder.”

The grounds and home, currently operated by the City of LA Department of Recreation and Parks, are open to the public on Saturdays and Sundays from 10 a.m. to 3 p.m.

Like Lummis in his waning days, El Alisal is a bit down-at-the-heels.

But the doors, arches, windows, stonework and sprawling grounds retain their original charm. You can almost hear the echoes of “noises,” lasting far into the night, with poetry recitals, guitar strumming and dancing.

The shadowy corners whisper, even now, of intrigues among the wives, lovers, seductresses and hangers-on with whom Lummis surrounded himself.

He died of cancer on Nov. 25, 1928. In “El Alisal: Where History Lingers,” Jane Apostol wrote of the friends who gathered for a service under a tall sycamore on the patio. In lieu of a hymn, they sang “Adiós, Adiós, Amores.”

And novelist Eugene Manlove Rhodes noted, “In 20 ways Lummis was the most remarkable man I ever knew. … He finished what he started and he paid for what he broke.”

Heather King is a blogger, speaker and the author of several books. For more, visit heather-king.com.

Interested in more? Subscribe to Angelus News to get daily articles sent to your inbox.