Every Lenten season for the past few years I’ve made a point of reading a book that I know I ought to read but have been avoiding.

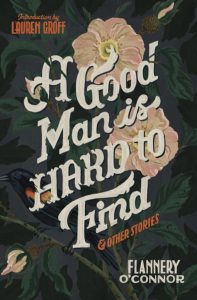

This year I’m reading the work of Flannery O’Connor in “A Good Man is Hard to Find and Other Stories.” I first read one of her novels when I was in college and found it too bleak. But now, my more mature mind and more experienced heart are finding the 20th-century Catholic author’s fiction illuminating in ways I never imagined possible.

Don’t get me wrong. Traveling with her characters through their dark days and wrenching internal conflicts is no walk in the park. It is tough work, actually. They are stories of violence, ignorance, abuse, despair — all burnished with a carnival freak-show overlay which conveys a sense of horror.

Her tales are set in the Deep South during the Jim Crow era, and all the pathologies and dysfunctions of that time and place are not just present but magnified. Perhaps the grotesque reputation that much of the American South still suffers from to this day (even when so many know it as a delightful part of the country to live, work, and raise a family) may be partially O’Connor’s fault, who used the world she knew to write stories dusted with the macabre.

Part of the author’s aim, I think, was to graphically plumb the depths of the caverns of sin in the human soul for the reader. In this there is nothing special, as there are countless books of psychological horror, crime, and violence that do the same.

Rather, it is her purposes for doing so that are special. She didn’t mean to simply titillate and horrify as many of her fellow novelists did and still do. No, she measured out the depths of human wretchedness so that we could stand amazed, with her, at the “appalling strangeness of the mercy of God.” to borrow that perfect phrase from Graham Greene, another great Catholic author.

We are meant to experience that no matter how deep the ancient fault lines of original sin may lie, they can overflow with the torrent of grace that gushes from the Savior’s side. The magnanimity of God flashes upon us, her readers, as she forces us to come to a stop and think: thousands upon thousands of human years of vile acts, casual cruelties, and stony indifference to our brother’s suffering have not begun to exhaust God’s tender clemency.

In her short story “A Good Man is Hard to Find,” one of her characters, the Misfit, a murderer on a random killing spree, expresses the vast implications of our redemption.

“If He did what He said, then it’s nothing for you to do but throw away everything and follow Him, and if He didn’t, then it’s nothing for you to do but enjoy the few minutes you got left the best way you can — by killing somebody or burning down his house or doing some other meanness to him. No pleasure but meanness.”

This is the conclusion that all of O’Connor’s works point toward. All of us — man, woman, child — have but one way out of our natural condition of “no pleasure but meanness”: coming face-to-face with our sinfulness, discovering we cannot conquer it on our own, and throwing away everything to follow the One who can and for some inexplicable reason does.

For O’Connor’s characters, that first step is the hardest one. Almost all of them seem to stumble around in a tragic blindness of spirit, entirely unaware of the cruelty of their acts and the pitilessness of their treatment of others. When they do feel compunction and aim higher, they are quickly defeated by habits of thought, the smallness of their minds, and the narrowness of their vision. They remain trapped by conceit and self satisfaction.

This brings me to another purpose of O’Connor’s — the one which I found particularly fitting in this time of Lent: to show us that we are just like them! We do not begin to see the wounds we inflict on others, or the edifices and habits we build to daily soothe our complacent consciences. Can we really claim to be superior to her characters, who were largely supine in the face of the grave societal injustices of the Jim Crow era?

We have our own modern day systemic cruelty that we’ve become accustomed to, but it does not seem to stop us in our tracks. The sexual liberation that our culture prizes above all goods is built on the backs of abased women and the deaths of untold numbers of unborn children.

We live in a society that values personal satisfaction and comfort, usually at the expense of the poorest and most vulnerable. Do we stand and protest against today’s grave sin and refuse to be a part of it?

So far, it has been a spectacular Lent for me, thanks to O’Connor. I’m dragging a very humble heart up the hill to Calvary. Not humble enough, I’m sure. But I can thank her for showing me there’s enough “appalling mercy” at the foot of the cross to make up the difference.