“If other ages felt less, they saw more, even though they saw with the blind, prophetical, unsentimental eye of acceptance, which is to say, of faith. In the absence of this faith now, we govern by tenderness. It is a tenderness which, long cut off from the person of Christ, is wrapped in theory. When tenderness is detached from the source of tenderness, its logical outcome is terror. It ends in forced-labor camps and in the fumes of the gas chamber.”

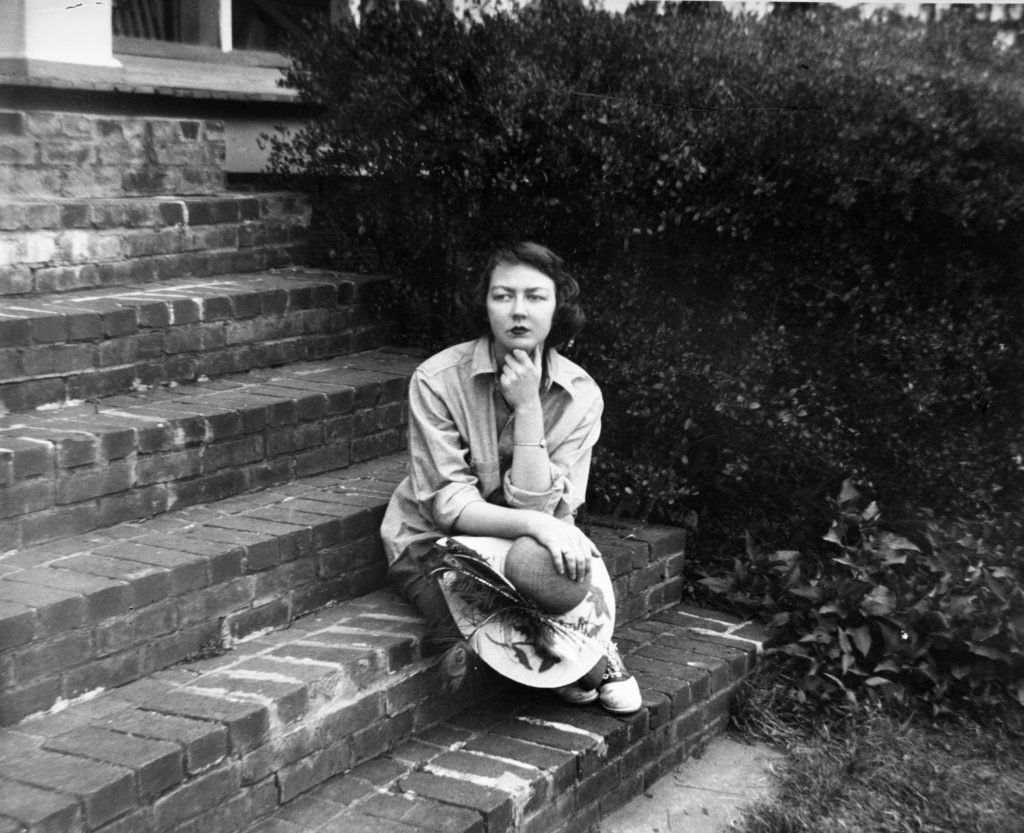

— Catholic novelist and short story writer Flannery O’Connor

Way back in the 1950s and ’60s, Flannery O’Connor foresaw the doleful effects of contemporary identity politics.

“On the subject of this feminist business,” she once wrote to a friend, “I just never … think of qualities which are specifically feminine or masculine. I suppose I [divide] people into two classes: the Irksome and the Non-Irksome without regard to sex.”

That’s shorthand for saying I judge people — I like people — according to their character, not their labels.

O’Connor was born, raised, and lived most of her adult life in rural Georgia. She also attended the Iowa Writers Workshop, lived in New York City for a time, and liked to read a few paragraphs of Aquinas’ “Summa Theologica” before going to bed.

Struck down with lupus in her 20s, she returned to Milledgeville to live out the rest of her life — she died at 39 — with her mother, Regina, a widow who capably ran a dairy farm.

Contemporary academics, perhaps a touch too gleefully, have “exposed” O’Connor’s racism: she famously turned down an opportunity, for example, to join Regina in hosting James Baldwin at their home.

In mid-century rural Georgia, a social code had been worked out by which to her mind both blacks and whites could operate while retaining their privacy and dignity. That’s not to say the code was ideal, or right.

But she would not try to make herself look virtuous or tolerant by participating in an insincere charade.

She would not throw Regina — who supported and loved her — under the bus. “In New York, it would be nice to meet [Baldwin]; here it would not,” she wrote to a friend. “I observe the traditions of the society I feed on — it’s only fair.”

In fact, she was “an integrationist on principle and a segregationist by taste”: “About the Negroes, the kind I don’t like is the philosophizing prophesying pontificating kind” (among whom she counted Baldwin, while also applauding some of his work).

Change should and would come. But to divide humankind into victims and oppressors with the oppressors all bad and the victims all good, O’Connor well knew, is a lie at least as dangerous as the lie undergirding racial prejudice.

Some of her favorite protagonists are nihilistic college grads who try to shame their elders into socio-political enlightenment, with deliciously tragicomic results.

They seldom have jobs, these young intellectuals. They’re disabled (Hulga in “Good Country People” has a wooden leg), or neurasthenic (Asbury in “The Enduring Chill”), or suffer from a heart condition (Wesley in “Greenleaf”).

Though adults, they’re supported by their hard-working, hopelessly backward mothers. Julian in “Everything That Rises Must Converge” almost dies of embarrassment when his mother — condescendingly to his mind, kindly to hers — offers a penny to a young black boy. In “Revelation,” a sullen girl reading a book called “Human Development” hurls it at Mrs. Turpin’s head, whispering “Go back to hell where you came from, you old warthog.”

We must be “nice,” such clear-eyed activists insist. We must not offend. We must enlarge our horizons. No one must feel “unwelcome.” We must exercise compassion — though not, of course, toward the unenlightened.

Based on the criteria of this godless, self-appointed moral elite, the unenlightened must instead be forced to be “good.”

As O’Connor recognized, without faith such “compassion” eventually requires us to ignore what is right in front of our faces, to spout absurd untruths, to contort every event to fit a templated narrative, and to be stripped of our right to like who we like based on Irksome vs. Non-Irksome or whatever criterion we darn well please.

Such “tenderness” would destroy a child in the womb rather than let him or her be born into poverty. Such tenderness eventually invites the addicted, the elderly, and the diminished to kill themselves. “Let us think for them!” exclaim the tender. “Surely they wouldn’t want to be a burden.”

O’Connor was a daily Mass-goer and, by all accounts, a lifelong celibate.

“I went to St. Mary’s as it was right around the corner,” she wrote of her neighborhood church, “and I could get there practically every morning. I went there three years and never knew a soul in that congregation or any of the priests, but it was not necessary. As soon as I went in the door I was at home.”

That probably describes the situation for many of us at our “neighborhood” church. The Church doesn’t much welcome anyone, in the way of the social-club welcome demanded by today’s aggrieved. It welcomes us as members of the soul-sick, as those ravenous with hunger and need of the Eucharist.

Lent is a good time to remember that Judas, keeper of the purse, was the über virtue-signaler, primly suggesting giving money to the poor rather than wasting it on nard to anoint Jesus. Then he sold his friend for 40 pieces of silver.

Or as O’Connor once observed: “The operation of the Church is entirely set up for the sinner, which creates much misunderstanding among the smug.”