A big part of what made Flannery O’Connor stand out as a Catholic writer was her honesty about sin — including her own.

“Ideal Christianity doesn’t exist,” she once wrote to a nun, “because anything the human being touches, even Christian truth, he deforms slightly in his own image.”

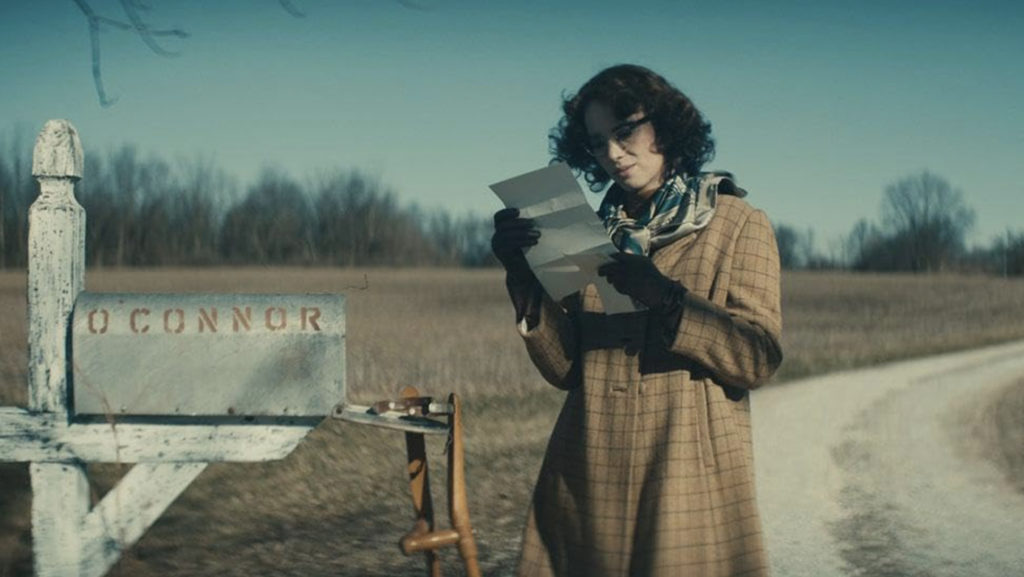

O’Connor’s life — and her stories — form the basis of “Wildcat,” a long-awaited film directed by Hollywood actor Ethan Hawke, and written by Hawke and Shelby Gaines. “Wildcat” stars Hawke’s daughter Maya as O’Connor, and includes performances from Philip Ettinger as the poet Robert Lowell and Liam Neeson as a priest who visits O’Connor’s bedside. The film, like O’Connor’s stories, is ambitious. But in attempting to emulate her ambition, it falls short.

Such a result was perhaps inevitable. Ethan Hawke’s vision is passionate; he clearly enjoys and appreciates O’Connor’s fiction. Yet she was both a singular and strange talent. Her strangeness arose from a willingness to embrace and channel the mystery of her art, a Catholic vision of the world. The film depicts a scene at a party where writers at a dinner table speak skeptically of the Eucharist, including Elizabeth Hardwick, who dismisses it as merely a symbol.

O’Connor responds: “Well, if it’s a symbol, to hell with it.” It’s a great line, and it affirms O’Connor as a defender of the faith among secular intellectuals. Yet the line lands oddly in the film — and encapsulates one challenge in adapting O’Connor’s life for the screen.

In “Wildcat,” the quip about the symbol is spoken by a Protestant writer at a party in Iowa City. The reality is much different. In a December 1955 letter, O’Connor described the event as a scene. Around 1950, O’Connor went to dinner with Lowell and Hardwick, along with Mary McCarthy, a novelist who grew up Catholic but left the Church. O’Connor felt terribly out of place.

“Having me there,” O’Connor recalled, “was like having a dog present who had been trained to say a few words but overcome with inadequacy had forgotten them.” McCarthy, in reality, was the one to make the comment about the Eucharist being a symbol — the comment having the sharpness of a Catholic who had left the faith, and now only appreciated it for its literary trappings.

This isn’t merely splitting hairs. By having Hardwick deliver the line in the film, O’Connor comes off as a provincial, small-town scold who corrects a Protestant on a manner of doctrine. In reality, O’Connor was challenging a fellow Catholic to confront her lost faith. She was affirming the real presence of Christ.

Film is always fiction; a movie requires a bending and flattening of reality. Yet the revisions to O’Connor’s life in “Wildcat” — including an implied attraction between her and Lowell, who is recast in the film as her professor — distract from the arresting, central story of her life.

The film is at its best when it creates sharp, almost hallucinatory moments that blur O’Connor’s life and her fiction. O’Connor often wrote about Christians who skewed religion in their own interests, including literalists whose misunderstanding of Scripture led to prejudice.

That vision comes alive in the film’s depiction of her story “Parker’s Back,” a brilliant tale of how a fundamentalist woman falls for a heavily tattooed, often acerbic man. In the story, Sarah Ruth and Obadiah Elihue Parker make an unlikely couple; she is attracted to him, but also repelled by his atheism.

After an accident stirs his fascination with God, he gets a deeply intricate tattoo of the face of Christ on his back. He returns to Sarah Ruth and takes off his shirt, hoping that she will recognize his faith and accept him again, but she reacts violently, screaming at him that the tattoo is sinful. Her fundamentalist view causes her to mistake iconography for idolatry; in ways both literal and metaphorical, she is unable to see Christ when he is right in front of her.

Maya Hawke’s portrayal of Sarah Ruth and Rafael Casal’s performance of Parker show two people falling into each other in lust and repelling in anger. Hawke, as director, almost seems freed in these moments of depicting literature rather than life. O’Connor died at 39 from lupus; her existence was marked by suffering. She lived through her characters; not through a desire to be like them, but to investigate the mysteries of this world.

“Wildcat” is marked by an unusual structure, interspersing real and imagined moments without transitions, effectively capturing the drifting and brilliant mind of a fiction writer. Yet the challenge of the movie is that it will make the most sense to those who already know O’Connor well, and it will frustrate those same viewers. The blessing and burden of O’Connor, perhaps, is that we can never recreate her short, troubled, and brilliant life. Her fiction is her best testament.