John Buchan’s “Thirty-Nine Steps” was a famous spy novel published in 1915 dealing with German spies in Britain on the eve of the First World War. Beloved in Britain, it was adapted for cinema several times, once by Alfred Hitchcock in 1935.

Its hero, Richard Hannay, is a mining engineer returned to England from Rhodesia and, at the beginning of the story, he is bored. Reading a newspaper about the crisis in the Balkans, he quips, “It struck me that Albania was the sort of place that might keep a man from yawning.”

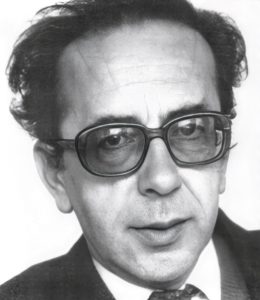

When I heard of the death of Ismail Kadare, Albania’s most famous writer, on July 1, I revised Buchan’s quote to say that Albania was the sort of place where a writer might produce works that would keep a man from failing to think about his place in the universe.

Although not well known in the U.S., he was a writer of international stature and an author for more than his own troubled times. Both Albania and Kosovo honored him with two days of official mourning.

Albania is a country of only 3 million people, but its suffering has crystallized into enduring works of literature. W.H. Auden’s poem on Yeats has a line, “Mad Ireland hurt you into poetry.” Albania’s mad history — the Balkan nation went from small kingdom to Italian occupation, then Greek invasion, responded to by Nazi blitzkrieg, succeeded by a postwar Communist regime that only collapsed after 1990 — hurt Kadare into poetry and parable.

His novels have been compared to Kafka and Orwell, which illustrates that politics is not the only field of human endeavor known for strange bedfellows.

Kadare was accused of cloaking his fictions with historical trappings in order to criticize the Communist government of the infamous dictator Enver Hoxha. That is not false but does not convey the transcendent symbolism of his parables.

His stories are about Albania, but even more about humanity and the ambivalence of history, beginning with his first novel, “General of a Dead Army” (1963), which tells the story of an Italian General who comes to Albania twenty years after World War II to retrieve the dead bodies of soldiers killed in battle.

“The Pyramid” (1992) is framed as the story of the construction of the Pharaoh Cheops Pyramid in ancient Egypt. When Cheops mentions that he doesn’t want a pyramid built, a courtier tells him:

“In the first place, Majesty, a pyramid is power. It is repression, force, and wealth. But it is just as much domination of the rabble; the narrowing of its mind; the weakening of its will; monotony; and waste. O my Pharaoh, it is your most reliable guardian. Your secret police. Your army. Your fleet. Your harem. The higher it is, the tinier your subjects will seem. And the smaller your subjects, the more you rise, O Majesty, to your full height.”

In these few sentences, Kadare captures totalitarianism better than the philosopher Hannah Arendt. The book is relentless about the pursuit of power and yet slyly humorous. “Life under Communism was principally a tragedy,” Kadare writes, “but a tragedy with comic, not to say grotesque, interludes. Life over all could be described in those terms, as a tragicomedy.”

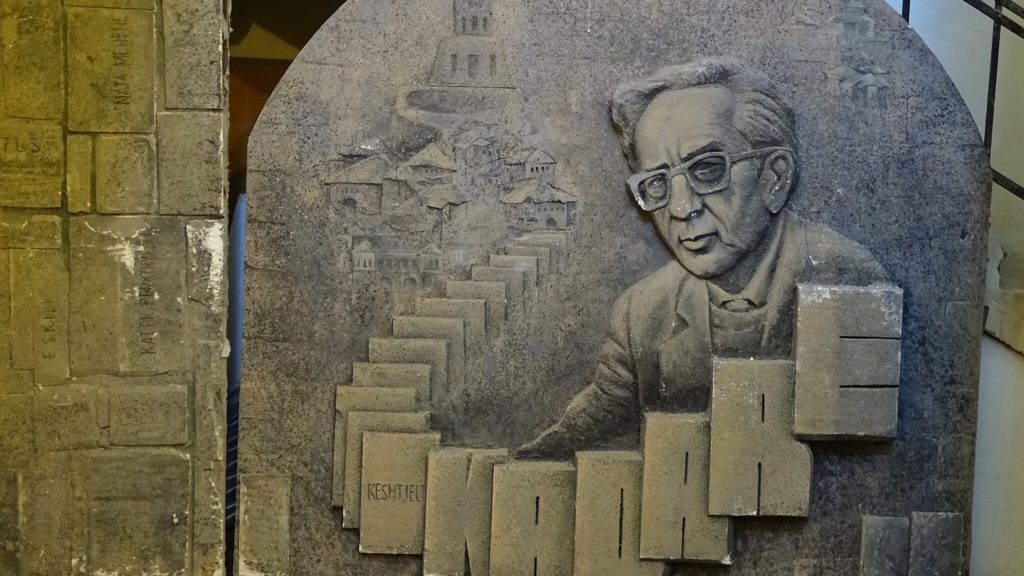

Several of Kadare’s books deal with his village, Gjirokaster, ironically also Hoxha’s hometown. In fact, the Hoxhas lived down the street from Kadare’s family on Lunatics’ Lane, a name so impossibly ironic it could have come from one of his fictions.

Another of Kadare’s parables has to do with Albania’s isolation. It was the last outpost of Maoist communism in Europe, after Hoxha fought with Stalin. The Three Arched Bridge (1978), set in the 14th century, is a tale about the building of a bridge connecting Albania with Greece.

Narrated by a monk, it reminds me of Thornton Wilder’s Bridge of San Luis Rey. The difficulties of the construction of the bridge, symbolic of connection with the greater world, are not just natural but human. The bureaucratic bungling and human conflict are sketched by the musing cleric and, as a finale, the bridge serves to help the invading Turkish army.

Kadare used the symbol of Turkish domination as a mirror to totalitarianism. The monk is given a vision of the “Ottoman hordes flattening the world and creating in its place the land of Islam…And above all I saw the long night coming in hours, for centuries.”

In The Palace of Dreams (1981), Kadare imagined a secret government agency in the Ottoman Empire that records the dreams of its citizens to better control them. The internet might one day make that paranoid parable a reality.

The national mourning for Kadare was picturesque and a testimony to the power of real literature to inspire: people threw flowers at the hearse that carried his body through the streets of the capital. It is impossible to imagine something like that here.

The Prime Minister of Albania, Edi Rama, gave a moving eulogy, pointing out the irony that the ceremony was taking place not far from an art installation celebrating St. Mother Teresa, the most famous Albanian, for whom the airport in the country’s capital, Tirana, is named.

Kadare was born to a Muslim family and professed to be an atheist. Nevertheless, the Prime Minister invoked the saint for the writer:

“No one orchestrated Mother Teresa’s presence over Ismail during this state ceremony. She was here. She had arrived earlier. I was informed that the stage was booked, and Mother Teresa could not be moved. I was given a photo of this stage, set for an evening event. Leave it there, I said, it couldn't be better. No one could have anticipated the coincidence that brought this, especially for Ismail, and no ceremony could better mark the passage of this Albanian’s life belonging to the world than under her shadow.”

Rama mentioned that Kadare had won many literary awards but not the Nobel Prize for Literature. So much worse for the Swedish Academy. And also for his enemies in Albania, whom the Prime Minister faulted for “anonymous letters” that blocked his winning the accolade although he was nominated for it fifteen times.

“He lived as a witness to a word for which he garnered all praises and possible honors worldwide yet encountered the enviousness of his birth land,” the prime minister said.

Tolstoy and Proust and many other great writers did not win the Nobel Prize for Literature, either. But Kadare left a spiritual legacy.

At an awards ceremony, he spoke of some of his writing comrades in Albania who manifested solidarity in dissidence to the oppressive regime. “We propped each other up, as we tried to write literature as if that regime did not exist. Now and again, we pulled it off. At other times we didn’t. The idea that we could create a few mouthfuls of spiritual nourishment for our imprisoned nation filled us with joy.”

Those “mouthfuls of spiritual nourishment” Kadare spoke of are a tremendous gift. The Spirit blows where it wills, and sometimes uses unlikely instruments to make a music for the soul.