Before I embarked to do pastoral work in El Salvador, I began preparing to learn the Spanish language. I decided that my fluency would be gauged by my ability to read literature in the language. Since literature is thought to be the speculum vitae, the mirror of life, I picked up some famous Latin American novels, first in English.

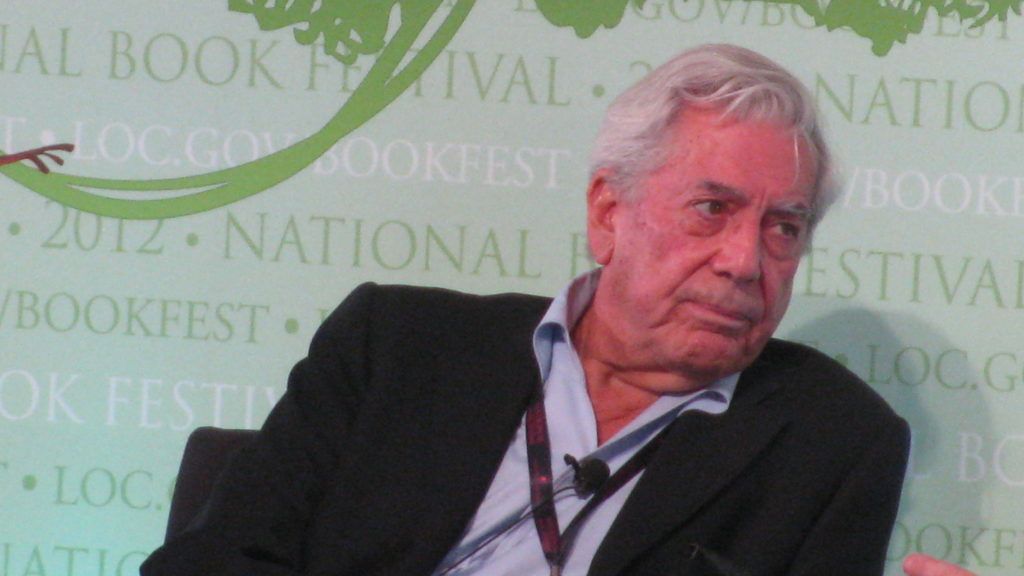

One of them was “Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter” (Picador, $21), by Peruvian author Mario Vargas Llosa, who won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2010. I have been thinking about him since his death this past April.

I arrived for language and missionary preparation at a Maryknoll school in Cochabamba, Bolivia, in 1985. In the morning I attended language classes and tried to read Spanish in the afternoon. In the library of the institute I found “La Tia Julia y el Escribidor,” the same book I had already read in English.

My landlady saw I was trying to read the novel and said, “My neighbor is a good friend of Julia.” It took me a minute to figure out that she meant the character, Julia, the ex-wife of Mario’s uncle, the hero of the story. Mario pursues his “aunt” Julia, though she is 14 years older than his 18 years, and they marry.

The fictional Julia was based on the true one, who later, my landlady informed me, had written a book called “What He Didn’t Say,” providing her perspective on the relationship. Vargas Llosa left Julia and married his first cousin, while Julia moved on to a third husband, a Bolivian military man.

Reading something I thought was fiction and discovering it was not only autobiographical but connected to the neighborhood I was living in was a real revelation to me, my first experience of “magic realism.” Vargas Llosa used many of his own experiences in his fiction.

The author died after a debilitating illness. He had a full life, which his children testified to in a press release. President Macron of France, Frank-Walter Steinmeier of Germany, the Prime Minister of Spain, King Felipe VI, and a host of other famous people lamented his passing. The Republic of Peru announced a day of national mourning.

He was a man of many parts, not all of them inspirational. His novels are tremendous exercises in imagination, but sometimes remind one of an adolescent who never outgrew an obsession with sexuality. Some have accused the American John Updike of a similar problem, but our countryman, as polished as his prose was, never seemed to grapple with the great themes with which Vargas Llosa worked.

The author had an ambivalent and intense relationship with his native land. He wrote some of his greatest works while living in other countries. He said Peru was like an illness, something “incurable, intense, difficult, full of the violence that always characterizes a passion.” Although he was first ideologically left-leaning, he moved toward the right and eventually ran for president of Peru against Alberto Fujimori, who defeated him in a landslide. Raised a Catholic, he became an agnostic. His books reflect a classically Enlightenment and secular worldview.

He believed in the power of culture, particularly literature. He owed much to Faulkner but worshiped at the shrines of Victor Hugo and Gustave Flaubert. A wonderful speaker (I heard him give an address on the value of literature in understanding human life) he wrote great books of criticism. One about creative fiction is called “The Truth of Lies.” Often compared with Gabriel Garcia Marquez, he was by far the more intellectual of the two. They ended up on opposite sides of the political and cultural spectrum. While Vargas Llosa broke with Castro’s regime in Cuba, Garcia Marquez remained a fast friend of the dictator.

The Church spoke to neither of them, though not necessarily all her fault. But it illustrates, in my estimation, one of the great weaknesses of the Church in Latin America — the lack of culture of its leaders. The rampant secularism of the ruling elites in Hispanic countries is one of the most powerful cultural forces in its history, and the Church has not responded to it.

Where are the Catholic writers and thinkers in Latin America? Who could compare to the cultural background and intellectual preparation of a man like Vargas Llosa? The Catholic Church is on the way to a minority existence in these countries. Both secularism and Protestantism have rapidly encroached on historically Catholic territory and influence.

Despite the beatifications and the canonizations of saints in El Salvador, the Protestant churches are outpacing the growth and strength of the Catholic Church. The same can be said for Brazil and other places across the continent. Why is there so much creativity in Latin American artists and intellectuals, so much vitality in Protestant sects but so little in our Church?

Pope Benedict XVI often referenced a theme of the historian Arnold Toynbee, who proposed that minority groups within a culture are often more dynamic and creative and change the societies in which they live. Reading a man like Vargas Llosa and his interpretation of Latin America could stimulate some Catholic response to cultures that are ripe for a new kind of evangelization. The political theology, often crudely reductionist, that has dominated the last 50 years of what passes for Catholic intellectual life in Latin America, has not won over hearts and minds. A more existential dynamic is necessary.

That is why I wish more Catholics would read Vargas Llosa. His idea that there was always a crucial difference between the understanding of European and Latin American cultures, even when there were superficial similarities and what seems to be parallel language, could be a key for the United States also.

He was also pessimistic about the culture in general in the world. He wrote a book called the Civilization of the Spectacle, in which he criticized a worldwide culture where “the first place in the table of values is taken by entertainment, and distraction and diversion, the escaping of boredom is the universal passion.” The Church could certainly engage with this.

Religion and culture are wedded together, even when the culture seems to be moving away from traditional religious worldviews. Religion must wrestle with both high and popular culture.

To the clergy and the educated laity, I would say, “Better read than intellectually dead.” Vargas Llosa is a good place to start thinking about culture in general and Latin America specifically.