Many Angelenos will know that the Getty Villa, the museum built by the famous oil tycoon in Malibu, is not just designed in the likeness of a Roman countryside house, but is a full-scale replica of a real Roman mansion from the first century B.C.

What they may not know is that the luxurious Roman house after which the Getty Villa is modeled was buried in the infamous eruption of Vesuvius in the Bay of Naples in A.D. 79, the same catastrophe that erased the ancient cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum, killing as many as 10,000 people.

The Villa dei Papiri, named after the carbonized papyrus scrolls found there in 1752, contained one of the world’s most extraordinary treasures: the only surviving library from classical antiquity and the single largest group of classical statues ever to be discovered, alongside paintings, mosaics, furniture, and much more.

Now, some of its most valuable pieces come home — or at least, the closest thing to home — for a major exhibition at the Getty, one that allows an unprecedented look into the lives of the individuals crushed by one of history’s most devastating natural disasters.

At the time of the eruption, Mount Vesuvius had been quiet for so many centuries that people did not even know it was a volcano. The multiple warning signs that preceded the explosion of its hidden magma chamber were tragically disregarded.

Pliny the Younger, whose uncle the naturalist Pliny the Elder died heroically trying to rescue some of the victims, has left us a powerful description of the gigantic dark cloud of ashes that rose from the mountaintop, some 20-miles tall, turning the day into night.

According to Pliny, people cried for help to the gods, but others thought that there were no gods at all and that the end of the world had come.

Later observers had a simpler view of the role of the gods in the incident. An early visitor to the site scratched the words “Sodom and Gomorrah” onto the side of a house.

As in the Genesis account, for Jewish and Christian observers the eruption was a deserved punishment — either for the city’s immorality or as punishment for the Roman destruction of the temple of Jerusalem some nine years before — except that this time no one was warned by an angel to leave the city before catastrophe struck.

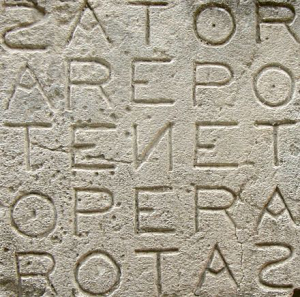

The so-called “Magic Square” which some scholars believe contains references to Christianity. (Wikimedia Commons)

The evidence is not conclusive, but the discovery of the mysterious magic square in one of the buildings in Pompei — a palindromic acronym that can be read in four possible ways and always yields the same sentence, and whose letters can be reassembled into two “pater nosters” (“Our Fathers”) — suggests that Christians (St. Paul convened with Christians in nearby Puteoli in the years before the eruption) or, more likely, Jews, may have perished in the disaster as well.

More than on the eruption itself, however, the exhibit focuses on the unique snapshot of the life of a Roman family of 2,000 years ago provided by the discovery of the Villa dei Papiri.

For lovers of ancient art, the exhibit is a sublime experience.

The Villa preserved an unusually high number of bronzes, which were more valuable and coveted in antiquity than marble statues. Some of them — such as the Amazon, the bust of a mythical female warrior, or the Doryphoros (Spear Bearer), a bronze copy of Polykleitos’ statue of the hero Achilles —— would have made even a Roman connoisseur like Cicero jealous.

Among the marble statues, the Athena Promachos, an impressive monumental image of the goddess of war and wisdom, easily dominates the show. It left a lasting impression on J.J. Winckelmann, the “father of art history,” who praised it as “the best of all marble statues.”

Athena Promachos (First in Battle), Roman, first century BC–first century AD, marble. Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Naples, 6007. (Giorgio Albano)

Alongside statues, the exhibit features other extraordinary survivors. The intense heat of the explosion carbonized the ancient scrolls present in the Villa’s library, preserving their otherwise perishable vegetable material while making them nearly impossible to unwrap.

The exhibit displays some precious specimens of unrolled carbonized papyri. Shriveled and wrinkled, they resemble a billy goat’s horn (as Winckelmann described them) and document the process that led to the successful unwrapping and publication of some of them (check out the 18th-century wooden “unwrapping machine”).

The exhibit also features videos showing how cutting-edge X-ray-based technology might soon be able to uncover the scrolls’ precious content without the need to unwrap them.

But what can the artifacts and the papyri tell us about the life of the individuals destroyed by the eruption?

Most of the papyri contain the works of the Greek philosopher Philodemus of Gadara, a fact that helped scholars identify the owner of the Villa as the powerful Roman politician Lucius Calpurnius Piso Caesoninus, father-in-law of no less a figure than Julius Caesar.

Both Philodemus and Piso followed the teachings of Epicurus, whose philosophy taught that there is nothing to fear in death, because the soul does not survive the body. According to Epicurus, the good life consists in enjoying the material pleasures of existence, like food and friendship, the satisfaction of basic needs and the removal of physical pain.

Fresco with a Window, Branch, Fillet, and Painted Panel, Roman, 40–30 BC, plaster and pigment. (Ministero Dei Beni e Delle Attivitá Cultural/Pedicini Photographers/J. Paul Getty Trust)

The philosophical credo of the Villa owner is reflected in the works of art he chose for its decoration.

It explains not only the presence of the little bronze busts of Epicurus and other philosophers displayed in the exhibit, but also the set of sculptures relating to the enjoyment of the pleasures of wine and food, such as the majestic Drunken Satyr, or the many statuettes connected to Dionysus (god of wine and relief from suffering).

The Villa is a meditation on life and death that goes beyond the dramatic circumstances of its destruction: Its texts and works of art reveal an ancient conception of the “good life” and of how to face the enigma of death.

But one might wonder: Were the residents of the Villa dei Papiri (assuming they still shared the Epicurean credo of its original builder) really so fearless in the face of death, and ready to retire from the world like a satisfied guest as Epicurus taught?

They certainly did not have time to think about it. The pyroclastic flood that slid down the slopes of Vesuvius (an avalanche of gases and magma that hit the city at some 60 mph with temperatures above 1,000 degrees F) killed them instantly.

Fortunately for us, we still have time to reflect on our view of what makes a “good life.”

Rather than wait for the next catastrophe, a special opportunity to do just that waits for us in Malibu.

“Buried by Vesuvius: Treasures from the Villa dei Papiri” is on exhibit at the Getty Villa in Malibu until Oct. 28.