Though a Presbyterian all his life, Catholics were always important and influential ‘neighbors’ to Fred Rogers

Fred McFeely Rogers is the subject of two major movies to be released this year: “Won’t You Be My Neighbor,” a documentary appearing in June, and “You Are My Friend,” a biopic starring Tom Hanks set for release in October.

The films mark a sort of canonization of “Mister Rogers” as a secular saint.

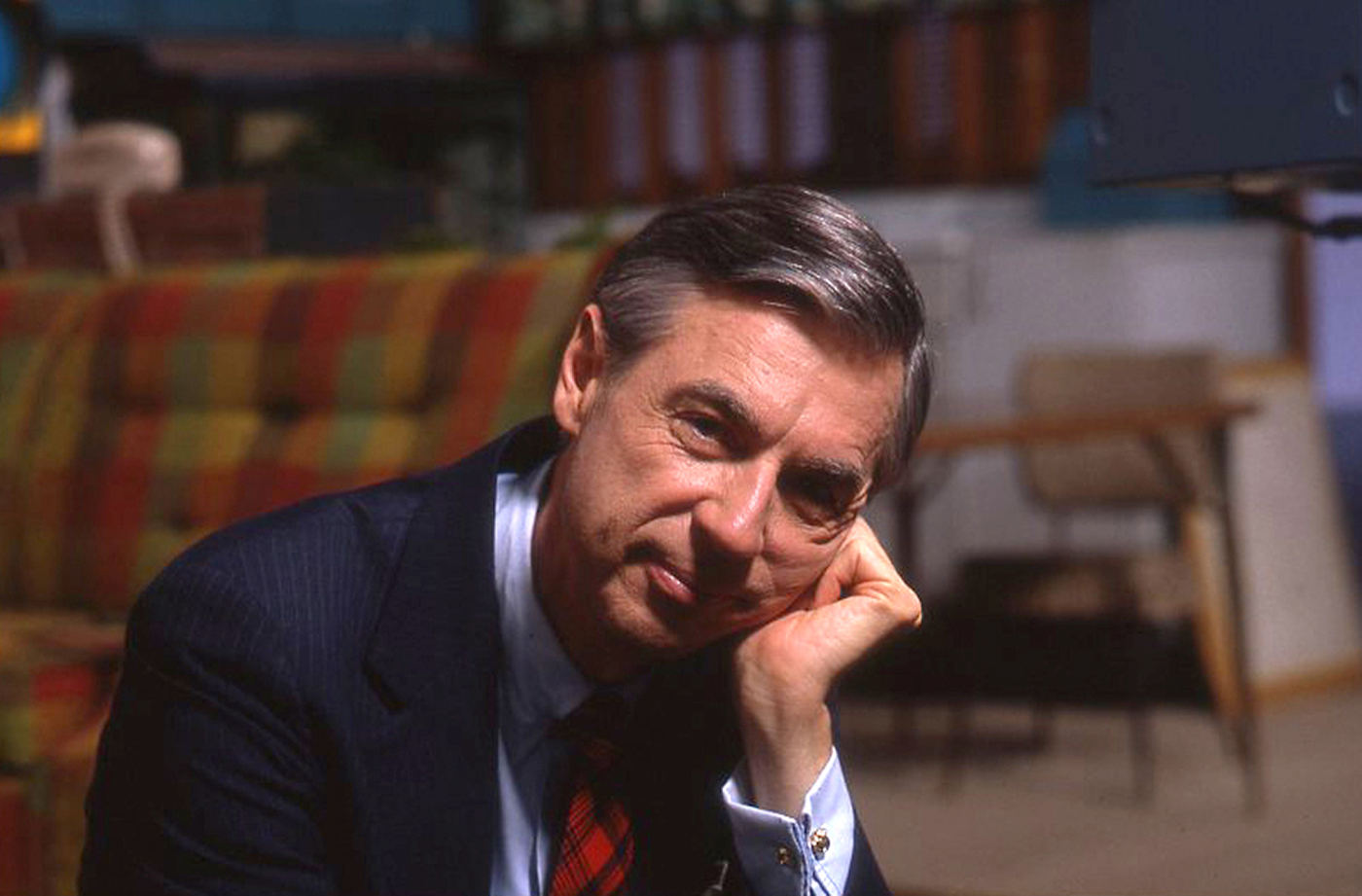

From 1968 to 2001, on public television, he hosted the children’s show that bore his name, “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood.” He appeared as a gentle, almost grandfatherly host, wearing a cardigan and sneakers, speaking slowly to the camera much of the time — or rather to each child watching.

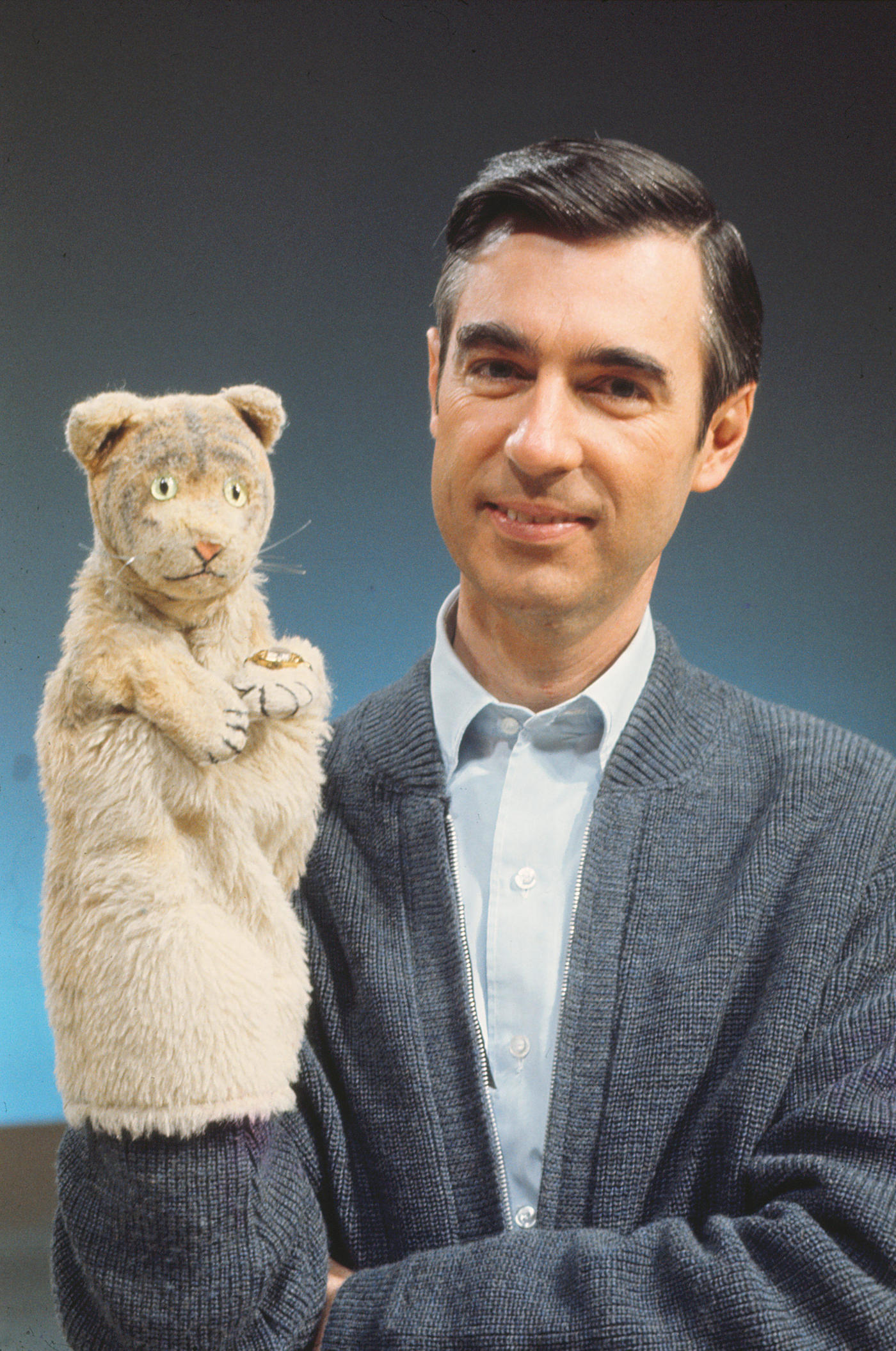

The show was almost entirely his creation. He conceived the “Neighborhood” as an imaginary world, ordinary in many ways, but peopled by a cast of both puppets (King Friday XIII, X the Owl and Henrietta Pussycat) and live human actors (such as “Handyman” Joe Negri and Chuck “Neighbor” Aber).

Rogers designed the puppets and voiced some of their parts. An accomplished jazz pianist, he even wrote music and lyrics for songs that made his lessons memorable.

His constant themes were kindness, politeness, thoughtfulness, civility, neighborliness.

He succeeded to a remarkable degree and was praised for his work, not only by his colleagues in broadcast media, but also by Congress and by presidents. More importantly, he set a new tone and agenda for children’s programming, which had previously been defined by slapstick violence.

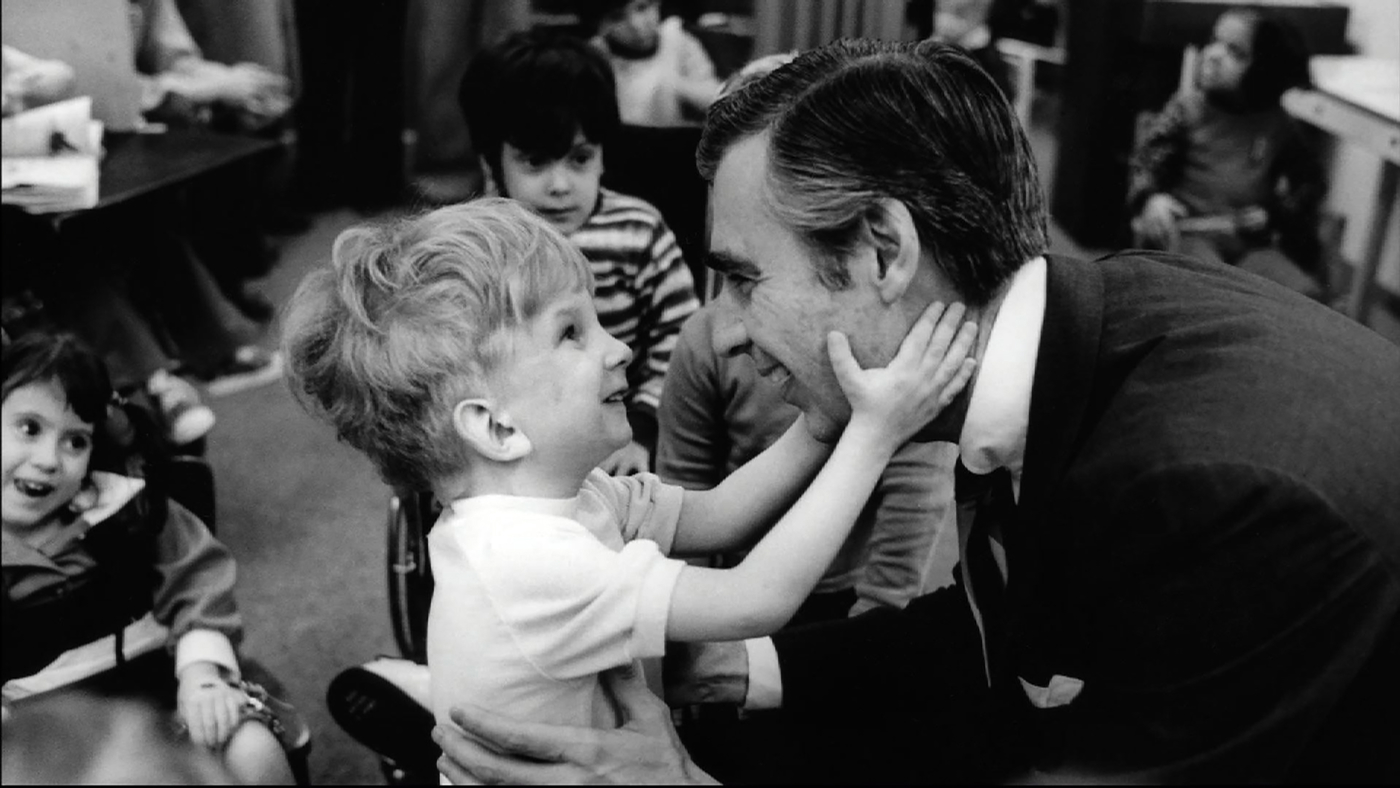

Rogers put the focus on learning virtuous habits — on understanding emotions and how to deal with them — on being a good neighbor and friend.

There was hardly a hint of religion in any of his programming. Yet Fred Rogers saw all his work as a Christian ministry, the ministry for which he had been ordained by the United Presbyterian Church. Though he remained a Presbyterian all his life, Catholics were always important and influential “neighbors” to him.

Rogers was born in Latrobe, a small town in western Pennsylvania, in 1928. Latrobe’s landscape is dominated by Saint Vincent Archabbey, the oldest Benedictine monastery in the United States and the largest in the Western Hemisphere.

“Saint Vincent was part of my very first neighborhood,” Rogers wrote in 1996. “I was always aware of its presence; nevertheless, the bonds of friendship are what made it real to me.”

He left Pennsylvania to study music composition in college, where he met Sara Joanne Byrd, who would become his wife. He worked a few years for NBC television in New York before returning home to work for Pittsburgh’s public-television station, WQED. He began also to take classes at Pittsburgh Theological Seminary, not far from WQED’s studios.

In 1963, Rogers graduated and was ordained for Presbyterian ministry. He was commissioned not for the pulpit, but specifically for work in children’s media.

He served a brief stint with the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, where he first conceived and launched his own show. In 1966, he moved back to Pittsburgh and took the show with him.

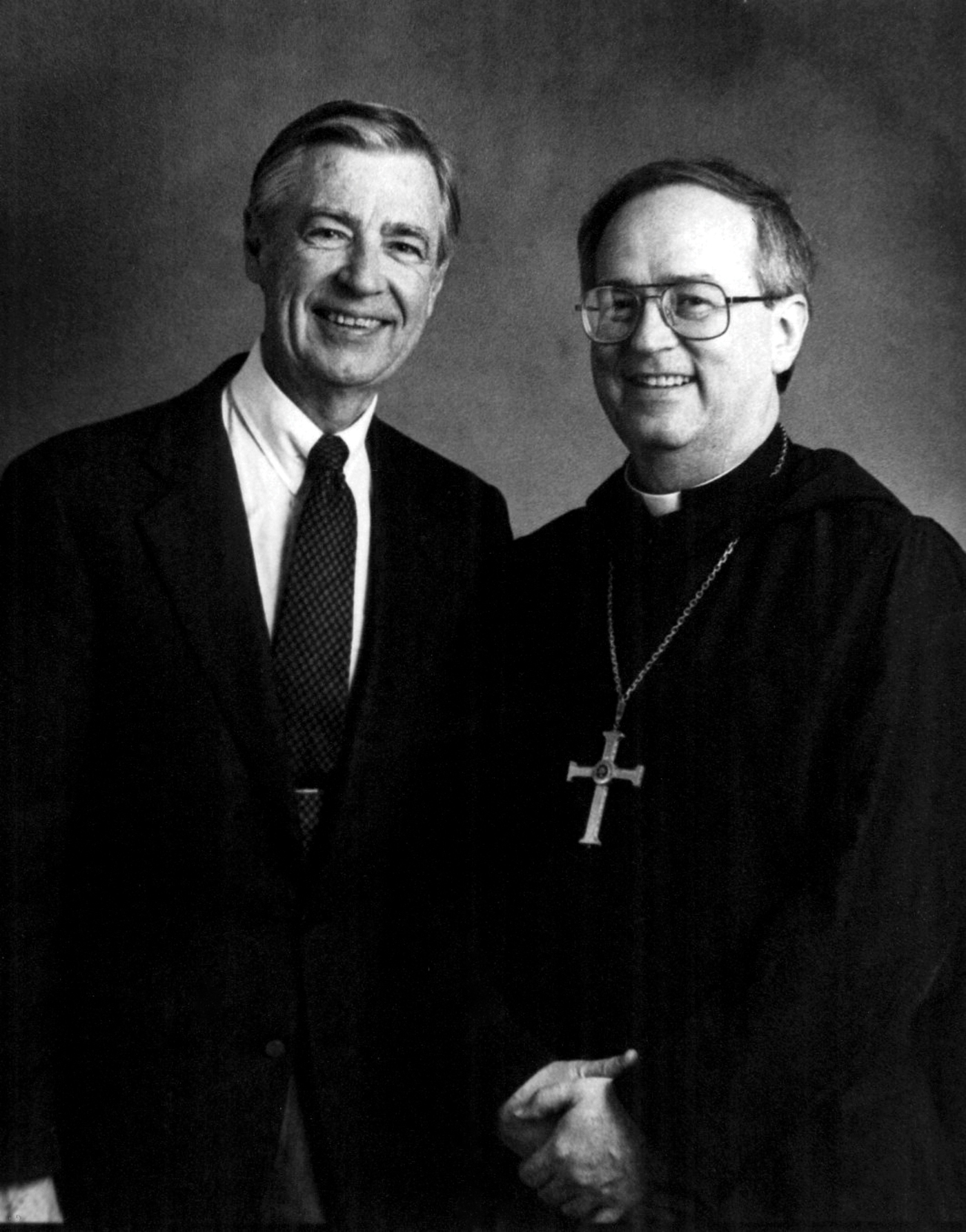

Shortly afterward, in 1967, Rogers met a young monk at Saint Vincent named Douglas Nowicki. They were to become close friends and colleagues.

A Catholic priest and a clinical psychologist, Father Nowicki traveled with Rogers to Mexico for service in orphanages. Rogers used documentary footage of their work in his 1978 PBS series for grownups called “Old Friends/New Friends.”

From 1978 to 1984 Father Nowicki served as a psychologist on staff at Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh and as a psychological consultant to “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood.”

“My office was not far from WQED where Fred worked,” recalled Nowicki, who is now archabbot at Saint Vincent. “I saw him daily during these years and consulted with him on many of the new programs he produced in the early 1980s.”

In 1986, Father Nowicki was appointed pastor of an inner-city parish — and chief administrator for educational programs in the Diocese of Pittsburgh. Those two jobs left him no time for television work, and he had to resign as a consultant for “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood.”

But Rogers was determined to keep working with his friend, so he volunteered at his parish. “Fred frequently helped in the distribution of food to families in need,” Archabbot Nowicki told Angelus News.

In 1991, when Father Nowicki was elected archabbot of Saint Vincent, Rogers was keynote speaker at the dinner following his Mass of Installation. In 1996, when the archabbey celebrated the 150th anniversary of its founding, once again Rogers was invited to give the keynote address.

In that second keynote, which was eventually published as “The Final Word Is Love,” Rogers acknowledged that our culture is in a moral crisis.

But he insisted that “violence, greed, hatred, even death itself is not the final word of our existence. We long to know that the final word is Love. God gives that Word for all of us who will receive it … through lasting friendships, through the trust of children, through the beauty and power of art and science, through forgiveness, through comfort in sorrow, through hospitality to a neighbor, and ultimately through Jesus the Christ our Lord.”

In his work on television, Rogers had rarely acknowledged religion or professed his faith. He was singleminded in his devotion to vulnerable children, and he probably didn’t want denominationalism or sectarianism to diminish his effectiveness. But Archabbot Nowicki sees his 1996 address as a key to understanding Rogers’ personal mission.

“This is the theology of Fred Rogers, which he so effectively translated into the language of American culture,” the archabbot said. “It was his contribution to offer the biblical message in simple language that would be understandable to children everywhere.”

Rogers was “a deeply spiritual man,” Archabbot Nowicki recalled, and he kept a disciplined life of prayer. “Fred loved the Scriptures and began each morning by reading the psalms and prayers of the Divine Office, with which he became acquainted during his many visits to the monastery.”

Rogers “often joined the monks for prayer and Mass.” And he had many other ties to the Catholic Church. He appeared on the catechetical program “The Teaching of Christ,” hosted by then-Bishop Donald Wuerl and aired on Pittsburgh’s CBS affiliate, KDKA. There, he was able to be more open about his Christian faith.

On camera, he cited the priest-author Father Henri Nouwen as a major influence, someone who “has helped me enormously.” He also quoted one of his seminary professors, who said, “The only thing that evil cannot stand is forgiveness.” And, Rogers added, “Jesus overcame that evil for all time with forgiveness.”

He counted many prominent Catholics among his dearest friends and associates. Joe Negri, an on-air companion, is also a composer of liturgical music, known for his jazz-inspired “Mass of Hope.” Mary Lou Williams, another Catholic composer of sacred music, was a favorite guest in “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood.” In an especially memorable show, she helped teach her host how to “scat” like a jazz singer.

In his appearance on “The Teaching of Christ,” Rogers said, “I think it’s the things that happen out of the spotlight, Bishop Wuerl, that are the important things.”

It is a remarkable statement from a man who spent so much of his adult life in the spotlight. His fame offered him a bully pulpit. He could have seized the opportunity, as other celebrities do, to posture as a pundit or a public intellectual. He could have ventured into politics or tried to barter political influence. But he didn’t.

He kept his focus instead on the most immediate needs of the most vulnerable children. He strove to be their friend and neighbor. The very titles of this year’s two movies bear witness to his success. Rogers maintained a singular sense of purpose and clarity about his vocation — and he believed that vocation was from God.

In 1997, when he received an Emmy Award for lifetime achievement, his acceptance speech was brief, and its centerpiece was 10 seconds of silence, in which he asked his Hollywood audience to remember gratefully the people who had helped them. He ended the silence with a prayer: “May God be with you.”

The neighborhood in the hereafter

Archabbot Douglas Nowicki recalled that his friend Fred Rogers “always prayed that he would ‘die well,’ which for him was trusting that the Lord was with him in his journey to the next life.”

Rogers was diagnosed with stomach cancer at the end of 2002 and died soon after, on Feb. 27, 2003. “He trusted deeply in the goodness of God,” Archabbot Nowicki said, “and embraced the moment of his passing with deep peace and joyful surrender.”

Mike Aquilina is a contributing editor of Angelus News and the author of more than 40 books, including “Love in the Little Things: Tales of Family Life” (Servant, $12).

Interested in more? Subscribe to Angelus News to get daily articles sent to your inbox.