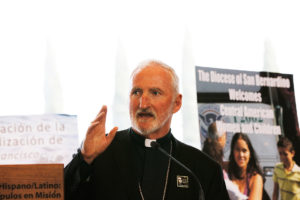

This story is part of a series featured in a commemorative issue honoring Bishop David O'Connell. Read more stories at the Bishop Dave Commemorative Issue web page.

Most of the stories of Bishop David O’Connell touching the lives of immigrant families and children have never been told publicly — perhaps because there are too many of them. But in the weeks since O’Connell’s Feb. 18 murder at his home in Hacienda Heights, the world has heard plenty of new ones.

An immigrant family reunited after being separated at the border; unaccompanied minors stranded in a foreign place receiving free tuition to Catholic schools; homeless immigrants suddenly finding a safe place to stay.

Bishop O’Connell often made it a three- or four-step process, showing how one act of outreach led to another.

A decade ago, he started the interdiocesan Southern California Task Force on Immigration while still a pastor in South LA. What began as an effort to simply provide assistance to immigrants had far-reaching effects of showing God’s love, mercy, and compassion.

And O’Connell was at the heart of it all.

Linda Dakin-Grimm, an immigration lawyer who worked closely with O’Connell on the task force, said that no matter the need, the bishop always had the heart to help.

“He always said yes,” Dakin-Grimm said. “I have seen him sit and talk and pray with people at shelters at the border who had been deported and had little reason for hope. He paid rent for immigrant families in LA who were not allowed to work and were in distress.

“Bishop Dave mentored the high school-aged unaccompanied young people whom he had sponsored at Catholic high schools in the city. He personally paid tuition for these kids, too. Once, when I told him that one of the boys had no place to stay, he drove to a shelter with a check to get the boy in.”

When the Arredondo family was separated at the U.S.-Mexico border after seeking asylum from their native Guatemala, the father, mother, and three daughters were reunited in Los Angeles more than a year later.

O’Connell personally provided for the family’s monthly rent, as well as the move-in deposit, for a house in South LA. He also coordinated for volunteers to help with translation, transportation, and donating furniture to the family.

When migrant unaccompanied children were stranded in the U.S., O’Connell worked with the task force and the Catholic Education Foundation (CEF) to enroll them into local Catholic schools — often quietly paying the tuition himself.

“For me, it really is a labor of love,” O’Connell said of the task force’s work in 2019. “Because this is, I think, what our schools and parishes are all about. Not just for unaccompanied minors but for all our children. There’s an epidemic of hurting children, even the ones who have too much. They feel we’ve abandoned them. And the migrant youths have become a metaphor for our whole society.”

Paul Escala, superintendent of LA’s Department of Catholic Schools, said he was impressed by how selfless and compassionate O’Connell could be.

“He had a budget to help children in this region,” Escala said. “The bishops have funds and he was always the first at the table to help when a school couldn’t make payroll … or a family. I knew that because before I could even ask, he was already there doing it.”

But O’Connell’s charity went beyond the financial. He walked the walk.

In 2018, O’Connell and other religious leaders participated in a grueling hike on both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border to experience the reality of a migrant’s journey. The trip, organized by the archdiocesan offices of Religious Education and Life, Justice and Peace, was called “Migrant’s Stations of the Cross,” which connected the passion of Christ with the suffering of migrants by artistically incorporating artifacts left behind by them in the Sonoran Desert.

In 2021, when unaccompanied migrant minors began arriving at emergency shelters in Southern California, O’Connell was one of several priests to celebrate weekend Masses for the children and to spread the love of Christ.

“My heart breaks for what these children have been through, and I want to help them any way I can,” O’Connell said. “Many [of the youth] have been through difficult times. Jesus invites each one with a friendship with himself.”

Why did O’Connell relate so much to immigrants, especially those from Spanish-speaking countries?

As many have observed, he certainly understood the immigrant experience, having come to the U.S. from a different country himself. Others have surmised that his profound sense of Christ’s example drove his actions.

“He just seemed to relate to immigrants and people who didn’t have much as his people — his peers,” Dakin-Grimm said. “He just seemed most at ease in the immigrant community with people who didn’t have much. That was home to him.”

“That shepherding wasn’t just about forming the structures, but it was his evangelization to families that didn’t look like him, families of color who spoke a different language that he learned, is so wonderful on the ears,” Escala said.

As a Latino, Escala said he found O’Connell’s connection to the community to be deeply authentic. “He came to understand the culture on a linguistic level and made Our Lady of Guadalupe his ‘patrona.’ ”

Those observations help explain how O’Connell saw this kind of ministry: not as social or political work, but a way of helping people come closer to Christ.

In his homily at O’Connell’s funeral Mass, his close friend Msgr. Jarlath Cunnane made clear what was behind the late nights: long trips, language lessons, and time spent with immigrant families.

“Yes, he helped the poor,” Cunnane said. “Yes, he fought for justice. But most of all, what he wanted to share was that encounter with Jesus Christ, that relationship with Jesus Christ.”