“The heavens declare the glory of God, the vault of heaven proclaims his handiwork.” — Psalm 19.1

The words of the psalm come naturally to mind as one visits the new exhibit at the Getty Museum, “The Wondrous Cosmos in Medieval Manuscripts,” which opened April 30 and runs until July 21.

For medieval artists and thinkers, the universe reflected the beauty and love of its Maker. The Getty’s display offers an unconventional exploration of medieval views of the cosmos through the pages of illuminated manuscripts.

Modern science has enormously increased our knowledge of the universe, and has provided us with breathtaking images of celestial phenomena, like the first-ever photo of a black hole recently released by scientists.

But the feelings associated with these sights are not always reassuring. For many, the cosmos evokes images of planets and galaxies far removed and indifferent to human beings, immeasurable expanses of darkness, catastrophic phenomena forming a spectacle that makes us feel small, irrelevant, and transient.

Not so for medieval artists and scholars, who saw the cosmos as a harmonious whole, whose signs and planets reflected God’s love and his eternal beauty.

Men and women of the Middle Ages had no doubt that the stars had a direct impact on their character, destiny, and even their everyday life.

Astronomy (the science of measuring the positions and movements of celestial bodies) and astrology (the doctrine that traced the correlation between celestial phenomena and the life of individuals) were seen as two sides of the same coin.

In principle, neither of them was incompatible with Christian faith: the planets, as servants of God, exercise an influence in accordance to his will.

Even the human body was believed to be under the influence of the stars. An illustration from a 1518 German manuscript depicts the so-called Zodiacal Man, a human body inscribed with zodiacal signs, each of them believed to have power over a particular body part. Leo, for instance, has power over the chest, while Libra governs the lower abdomen.

Stars and planets were necessary for marking times and seasons. Their movements could be calculated through appropriate tools, such as the mysterious Volvelle contained in a 14th-century manuscript from Oxford.

The rotating parchment disks of this complex movable diagram allowed users to calculate the positions of the sun, moon, and signs of the zodiac at various times during the year, while the accompanying tables allowed to calculate lunar phases.

This was necessary, for instance, for establishing the date of Easter, which has fallen on tradition on the first Sunday after the first full moon of spring.

For medieval thinkers the universe was, quite literally, harmonic: planets had a music of their own. The late antique philosopher Boethius (A.D. 477–524) elaborated a system, called the music of the spheres, in which each planet was attributed a musical value, corresponding to one tone in the scale.

An illumination from an early 15th-century manuscript shows Boethius explaining his theory to a group of students. He points to a golden globe, whose letters and inscriptions signify a musical tone, the diatessaron (a fourth above the tone), and diapente (a fifth above).

The medieval poet Dante explained music as a form of relationship: A beautiful melody is created by multiple sounds that relate harmoniously to one another. Thus, there is a correlation between music, beauty, and love.

In his “Divine Comedy,” Dante describes hell, the place where love is absent, as a cacophony of discordant noises. Paradise, on the contrary, is characterized by the music of angelic choirs and the harmonious sound of the celestial spheres.

This notion is captured by another item in the exhibit. In a 15th-century French book of hours, Mary and the child Jesus are portrayed as the center of the universe. The picture is surrounded by angels who sing and play instruments. The artist conceives the cosmos as a realm suspended between earth and heaven, filled with music and light.

In medieval thinking, the universe is not indifferent to the troubles of human beings, but rather participates in the history of salvation. Cosmic imagery permeates the Bible from the first to the last page, from Genesis to Revelation.

An illumination from a book of hours depicts God fashioning the planets. The scene accompanies a hymn that addresses God as “life-giving creator of stars, eternal life of believers.”

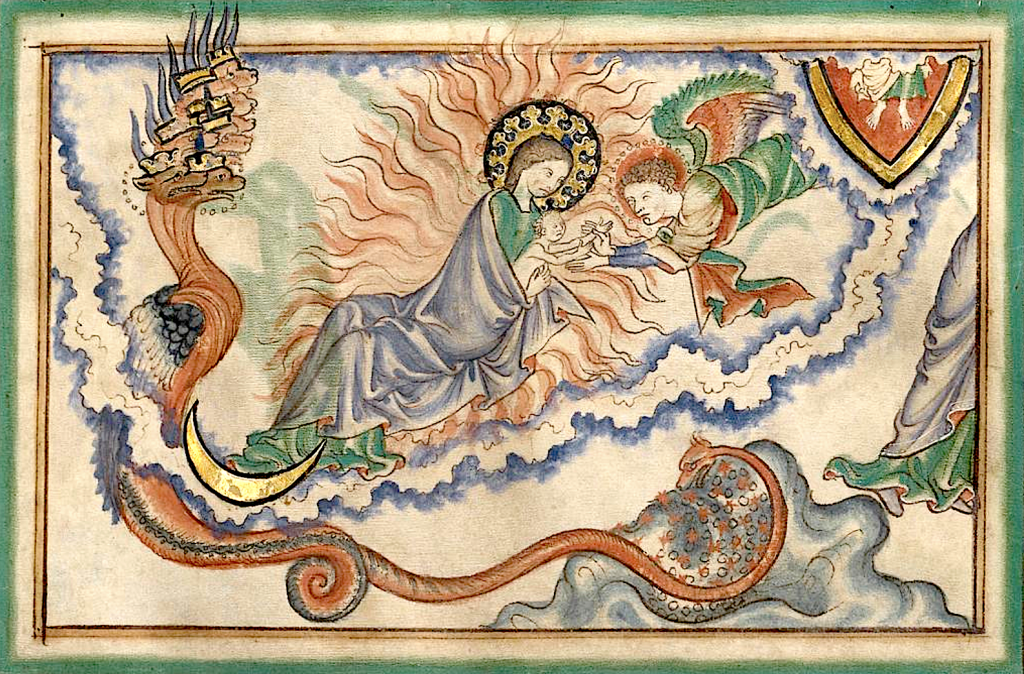

Some of the most impressive illuminations in the exhibit concern the final battle between good and evil recounted in the Book of Revelation. One illumination portrays a woman arrayed in the sun, with the moon under her feet and a crown of twelve stars.

The commentary tells us that the woman represents the Church, which gives light to both day and night. On the next page the same woman is threatened by a dragon (Satan), who traps the stars in its coils and drags them down from heaven, destroying the perfection of God’s firmament.

The Revelation’s cosmic battle appears in another impressive illumination from a 15th-century manuscript. Two warrior angels drive the prideful angels into hell, represented as the gaping mouth of a monstrous animal.

Cosmic events also mark the whole life of Jesus from birth to death. In an illumination from an early 15th-century book of hours, the Magi find their way to the child Jesus by following a star. The Wise Men’s astronomical inquiry leads them to the revelation, a powerful illustration of how science and faith can cooperate in helping humanity reach the truth.

The illumination by the French master Jean Bourdichon sets the death of Christ into a cosmic scenario. As in the Gospel’s account, Jesus’ death is accompanied by an eclipse. In Bourdichon’s version, the two major heavenly bodies, the sun and the moon, appear on the two sides of the cross against the background of a starry night sky.

Unlike traditional depictions of the crucifixion, Christ is here surrounded by a huge crowd of soldiers. It seems as though the entire cosmos, both humans and celestial bodies, is made to witness the passion of its Maker.

The presence of the sun and the moon evokes the account of the creation in Genesis. In Bourdichon’s interpretation, Christ is seen as the alpha and the omega — the beginning and the end of history.

Seeing the cosmos with our own eyes is a particularly challenging task for Angelenos, as the stars are hardly visible thanks to light pollution.

For a few more weeks, “The Wondrous Cosmos” provides an alternative way to contemplate the wonders of creation, and to explore ideas about God, science, and human destiny through the lens of Christian artists and scholars who came centuries before us.

Stefano Rebeggiani is an assistant professor of Classics at the University of Southern California.

SPECIAL OFFER! 44 issues of Angelus for just $9.95! Get the finest in Catholic journalism with first-rate analysis of the events and trends shaping the Church and the world, plus practical advice from the world’s best spiritual writers on prayer and Catholic living, along with great features about Catholic life in Los Angeles. Subscribe now!