Recognized today as one of the greatest British artists of the late 18th century, William Blake (1757-1827) produced art that was neither appreciated nor understood by many people of his time. His ideas are no less controversial now than they were 200 years ago, his prophetic vision a challenge to our cynical materialism and lazy middle-class ideals.

Since October, those ideas have gotten the treatment they deserve at a Getty Center exhibit titled “William Blake: Visionary” (open through Jan. 14) offering visitors a perfect opportunity to reencounter his genius.

Thematically divided, the exhibit follows Blake’s activity as printmaker, painter-illustrator, and painter-poet. One section (“Blake the visionary”) looks at Blake’s prophetic books (such as “America, a prophecy”) for which he used his special etching technique to combine word and image on the page.

Another (“Blake the Mythmaker”) focuses on Blake’s mythological world, with particular attention to his epic poem “Jerusalem: The Emanation of the Giant Albion,” which he illustrated with over 100 tables.

You don’t need to understand Blake himself to appreciate this exhibit. His phantasmagorical drawings are beautiful enough in themselves, his imagination too unhinged to fail to stimulate even the dullest of minds. But Blake did not think of art as something that is just pretty to look at. Rather, in his works, word and image complement each other.

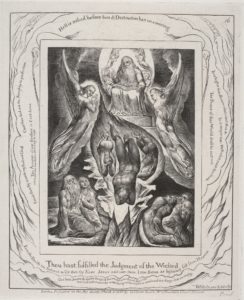

Take, for example, Blake’s engravings of the Book of Job, one of my favorite parts of the exhibit. In the first plate, the image of Job with his family is surrounded by a vision of harmony in the cosmos. In the last plate, Blake adds an element to the biblical narrative, a spectacular engraving with God casting Satan into hell.

Here the depiction of God seated in judgment evokes the image of Christ the redeemer, who returns man to communion with God, while at the same time recalling the cosmic imagery of harmony in the first plate.

For Blake, art was most of all a form of communication, which expressed eternal truths by way of its subjects and style. Blake saw the artists in the Venetian school that came after Michelangelo as decadent. His mission was to bring art back to Michelangelo’s formal perfection so as to render it a perfect means for communication. But what was he so eager to communicate?

Blake lived in a difficult, rapidly changing world. He lived through three major wars and the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, while witnessing the type of urban poverty and social misery that came with it. The exciting scientific developments in the aftermath of Sir Asaac Newton’s discoveries were accompanied by the rise of deism, a form of rationalistic religion which claimed to be superior to (and aimed to supplant) Christianity.

A Christian, Blake loathed deism and rejected the idea of a disincarnated, distant deity who held himself aloof over the misery of mortals.

At the same time, Blake did not adhere to any Christian denomination. For him, organized religion had stifled the revolutionary power and the freshness of the gospel’s message, disfiguring revelation to the point of making it unrecognizable. It was the role of art, he believed, to bring us back to being the creatures of God that we truly are.

An impressive drawing in the exhibit depicts Satan triumphing over Eve in the guise of an angel flying over a woman, whose body is ensnared in the coils of a serpent. This was humanity’s condition, in Blake’s view, and he believed that in his time Satan had found a potent ally in the demiurge Urizen. In one of the most iconic images of British art, also featured in the exhibit, Urizen appears as the Ancient of Days, intent upon dividing light and darkness with a compass in his hands.

In Blake’s mythology, Urizen is a satanic figure associated with science and organized religion. He is an embodiment of the chains of reason imposed on the imagination.

In another powerful biblical engraving, Blake depicts God in the act of reproaching Job. Who are you to contend with God, asks the Omnipotent? Here God proceeds to show to Job the monsters Leviathan and Behemoth.

These two monstrous, elemental figures, in the form of a pachyderm and a sea-dragon, represent all that is mysterious in the world. How dare men, the engraving seem to suggest, claim to know and grasp the universe in its complexity?

Blake saw this as the chief problem of his time. He detested his contemporaries’ materialism, their preoccupation with money and success, and (most of all) their claim to hold the world in their grasp through technology and science. And he believed that a scientific and materialistic worldview would inevitably give birth to societies characterized by oppression.

Through his paintings, engravings, and drawings, Blake conveys the sense that what we see is but a tiny fraction of what exists. There is an invisible, spiritual reality that pervades, precedes, and continues after the visible world.

This world is revealed to us through visions and dreams. In a mesmerizing drawing in the exhibit, Blake depicted a vision he claimed to have had, in which the ghost of a flea appeared to him (represented by a monster-like figure) and told him that all fleas were inhabited by the soul of men.

Did he actually see this in a vision? Perhaps. What matters is that for him art, vision, and prophecy are one. His flea represents the reality of middle-class men, who in their pursuit of comfort, money, and material pleasure, have closed themselves to the spiritual world that lies beyond appearances. In the process, they have turned themselves into insects.

This is what makes Blake’s work so relevant and controversial today: His art mocks the arrogance of men who believe only in what they can touch and see, and affirms the moral superiority of art and imagination over reason and science.