Leonardo Defilippis, the president and founder of Saint Luke Productions in the state of Washington, remembers when he had a chance a few years ago to approach Archbishop José H. Gomez to discuss a play he had recently completed and had been touring.

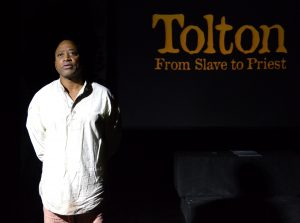

“Tolton: From Slave to Priest” chronicles the life and times of Father Augustus Tolton, born into slavery in 1854 before becoming the first African American Roman Catholic priest. Since Defilippis wrote and directed it, it has been presented more than 100 times since it debuted in 2017.

“When I told him about this, he looked at me and said, ‘I love Father Tolton,’ ” Defilippis said of Gomez. “That really touched me. I’ve been wanting to bring this to Los Angeles ever since. Finally, that door is opened. It’s very exciting.”

During the heart of Black History Month, and less than a year after Father Tolton was declared venerable by Pope Francis, moving him forward in the path towards sainthood, this one-man, multimedia presentation channeled through actor Jim Coleman has at least four public shows set this month.

Performances have been scheduled at St. Martin of Tours Church in Brentwood (Feb. 10), St. Andrews Church in Pasadena (Feb. 12), American Martyrs Church in Manhattan Beach (Feb. 13) and St. Monica Church in Santa Monica (Feb. 15) plus a private show at St. John’s Seminary in Camarillo was added for Feb. 18. More public shows may be forthcoming.

Anderson Shaw, director of the African American Catholic Center for Evangelization (AACCE), became an important driver in helping Defilippis’ efforts to put together an LA run of shows with parishes and facilities that had the space and financial resources to make it happen.

Shaw, a recipient of the Archdiocese of Los Angeles’ Cardinal Award from Archbishop Gomez in 2018, said he first caught a flavor for the play during a presentation at the National Black Catholic Congress about a year ago. He had been asked by Archbishop Gomez to participate on a team developing a pastoral plan for the African American community in the United States.

“I knew the archbishop admired him and was taken by the adversity he overcame,” said Shaw, whose AACCE group is also sponsoring the 15th annual Black History Mass at the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels Feb. 15 at 5 p.m.

“For me, Black History Month is always a time that emphasizes encouragement. We need to put things out there for folks that are positive in a time when so many negative things may be flying around. That’s where I come from. This isn’t about black, brown, yellow, green, or whatever. It’s about how we show the face of Jesus in those we encounter. There are so many ways to show them God is here for you as well.”

In August of 2006, a rather unassuming 255-page book written by Sister Caroline Hemsath for Ignatius Press titled “From Slave to Priest: A Biography of the Reverend Augustine Tolton (1854-1897): First Black American Priest of the United States,” was for many the first real knowledge of what Tolton endured.

St. Katharine Drexel, the second American-born saint canonized by the Catholic Church, was one of those interviewed by Hemsath before her 1955 death to talk about her interactions with Father Tolton.

The book starts to tell the story of someone born in Brush Creek, Missouri, with a baptismal record that simply reads: “A colored child born April 1, 1854, son of Peter Tolton and Martha Chisley, property of Stephen Elliott.”

After his father went to fight for the Union Army and was presumed dead in the Civil War, his mother took her three children and crossed the Mississippi River about 100 miles north of St. Louis, on a boat with just one oar, dodging Confederate bullets. They escaped to Quincy, Illinois, a free state.

Baptized Catholic, which was the Faith of his family’s owners, and also raised in the Faith, Tolton would be convinced that God was calling him to be a priest. But already cast out of a Catholic school because of racial prejudice, and unable to find a U.S. seminary that would admit him, he went to Rome, where in Italy, a man of his color was far more accepted.

Ordained at age 31 on April 24, 1886, at the Basilica of Saint John Lateran, his intentions of going to Africa as a missionary were changed; he would return to Illinois to become a parish priest.

Hemsath’s book tells about a conversation Father Tolton had with another cleric shortly before departing, in which he wondered whether America deserved being called by many the world’s most enlightened nation.

“If America has not yet seen a black priest,” Tolton said, “it must see one now.”

The news of his charismatic sermons raised jealousy with other Catholic priests as well as Protestant black ministers who thought he was stealing congregants.

Transferred to the other side of the state in Chicago, Father Tolton, known as “Good Father Gus,” established a parish that met in the basement of the Old St. Mary’s Church, while he built St. Monica Church, named for the African mother of St. Augustine.

If one cares to make the analogy that Father Tolton was something of the Jackie Robinson of his profession, it may be fitting to note that Father Tolton became a priest almost exactly 50 years before Robinson broke the Major League Baseball color barrier in 1947.

At age 43, Father Tolton died on July 9, 1897, after years of exhaustive travel across the country to evangelize. He is buried in Quincy, Illinois, and Catholic leaders in the area are trying to establish a shrine to Father Tolton at the now-closed Quincy church.

The Diocese of Springfield, Illinois, where Father Tolton ministered to the poor at the time of his death, had been trying to work on his canonization since 2003.

It wasn’t until 2010 when Chicago-based Cardinal Francis E. George began a four-year process to nominate Father Tolton for sainthood. After Cardinal George’s passing, African American Bishop Joseph Perry, also of Chicago, was named postulator for Father Tolton’s case of canonization.

“The broader African American community relishes the stories of people who got through enormous odds and did it in a Christian way,” Bishop Perry said in 2014.

Then again, it was not until June 2019, when Pope Francis designated Father Tolton as venerable for his “heroic virtue,” putting him two steps away from possible canonization.

The education that an intimate play such as “Tolton: From Slave to Priest” can help in bringing more awareness of the canonization process isn’t lost on Defilippis.

“In exposing this story for the first time to so many people, it’s profound to think we can help the movement,” said Defilippis, who worked both with Cardinal George and Bishop Perry in extracting historic research about Father Tolton’s life.

Defilippis, whose current touring dramas for Saint Luke Productions have focused on St. John Vianney, St. Faustina, St. Maximilian, and St. Augustine, said years ago he had been given a copy of the Hemsath book from a parish priest in the Diocese of Springfield, Illinois, and it has been on a shelf in his office. When contemplating his next project, Defilippis said he noticed the gaze of Father Tolton’s eyes off the cover of Hemsath’s book.

“I said to myself, ‘I think I’m being called to do him,’ ” said Defilippis. “I didn’t know anything about him either at that time. The look in his eyes gave me a whole new energy to expose someone who, to many, is still totally unknown.”

Coleman, a 58-year-old Florida-based actor known for his commercial work as well as a recurring role of Roger Parker on the Nickelodeon show “My Brother and Me,” grew up Baptist in an all-black section of Dallas, the son of a minister, who knew little to nothing about the Catholic religion growing up.

He simply calls playing Father Tolton life-changing.

“Having been in this business some 30 years, I’ve never been moved or touched in the way I have with this performance,” said Coleman, who started performing this role in January 2018.

“I pray to Father Tolton and ask him to intervene, to come and speak through me. The first time, I had no expectations of it actually happening. But it has. He speaks through me and I’m overwhelmed by the emotions.

“It has nothing so much to do with words of the play, it has to do with him telling his story and painting a picture and bringing people in to see his life. I feel I’m just a vessel for that. I truly feel his presence. I’m no longer there.”

Coleman said Father Tolton has taught him that “we are truly all one and we have to celebrate our divine likeness because we are all one in Christ. As a black man in America, this story still resonates with me. We think about the progression over the years, but in reality, they may have integrated schools in the 1860s, but it still took the Brown v. Board of Education law in 1954 to become a law. And it feels today we’re living almost in the same times. This separation of the country today, I feel it.

“Doing this as a play, I feel people are engaged immediately and the story touches their heart so much more than a movie or television show. Once you see this, and live his life and walk that path with him, hear the hate and discord thrown at him and yet see him maintain a spirit of peace and harmony, it’s just being there, you are part of it.

“I have seen so many tears. At seminaries, some students say they may have been at the verge of giving up but saw the show and know this is a path they must take. When I think about it, I think of him taking a path when there was no path and he created a path and his legacy continues to create a path for so many.

“I feel blessed and humbled to be a part of this play.”