A dozen times her name appears in the Gospels. That doesn’t sound like much, but her tally is greater than those of most of the apostles. And her appearances are more consequential.

All four Gospels tell us that she stood as a witness at the cross of Jesus. Matthew, Mark, and Luke say she was also at his burial. Most importantly, all four Gospels record her eyewitness testimony of the empty tomb.

If there was any indispensable witness to the events of Holy Week, it was Mary Magdalene. She alone saw everything.

Her given name is the most common female name in the New Testament. “Mary” was enjoying a surge of popularity in first-century Judea, probably because it had been the name of the favorite wife of Herod the Great.

“Magdalene” indicates that her place of origin was Magdala, a city on the western shore of Lake Tiberias. She is listed among the women who traveled with Jesus. The only other detail we know from her early life is that Jesus had delivered her from bondage to seven demons (Mark 16:9; Luke 8:2). Assuming that the demons had driven her to sin, some of the Church Fathers identified her with the sinful woman who anointed Jesus’ feet and bathed them in tears of repentance (Luke 7:39).

But that is speculation. Almost everything we know of Mary we learn from the final scenes in each of the four Gospels. There she is portrayed as the most steadfast witness.

Her role in the narrative is odd, to say the least. Women were rarely admitted as witnesses in Roman courts; and in Jewish courts their testimony was completely inadmissible. The Mishnah (compiled around 200 A.D.) insisted: “The oath of testimony is conducted with men and not women.”

Yet the Gospels are insistent that Mary Magdalene was the primary witness of these most important events. The evangelists seem to be leading with their chin. If the truth were otherwise — if any male had seen the risen Lord — the narrative would likely have included the man’s account and foregone the woman’s altogether.

But that was not the case. Mary remained at the scene of Jesus’ execution, even after his male friends had fled. She proceeded to his burial. She returned to the tomb as soon as the Sabbath had passed.

Her singular love made her bold in ways the men were not. She had known the torments of hell during her years on earth. She was possessed by seven demons until Jesus drove them out. He delivered her, and her gratitude was permanent.

St. John gives us the most detailed account of what Mary saw at the tomb. She appeared in the cemetery, he wrote, “early, while it was still dark,” and she “saw that the stone had been taken away from the tomb” (John 20:1).

Shocked, she ran to tell the disciples that Jesus’ body had apparently been stolen. She said: “They have taken the Lord out of the tomb, and we do not know where they have laid him” (v. 2). Peter and John returned with her to the scene, but did not understand the situation; and so they left her there by herself.

Two angels then appeared and asked Mary why she was weeping. She told them, “Because they have taken away my Lord, and I do not know where they have laid him” (v. 13).

She turned then to see a man standing nearby, and she did not recognize he was Jesus. He, too, asked the reason for her tears. Believing he was the gardener, she said, “Sir, if you have carried him away, tell me where you have laid him, and I will take him away” (v. 15).

Jesus spoke her name, and she immediately knew who he was. In her excitement, she must have moved to touch him or hold him. But he stopped her, saying: “Do not hold me, for I have not yet ascended to the Father” (v.17).

Instead, she received his command to “go to my brethren and say to them, I am ascending to my Father and your Father, to my God and your God.”

Then she went to the disciples again and told them, “I have seen the Lord”; and she told them what he had instructed her to say.

The passage is brief, but rich. According to one interpretive tradition, Mary’s meeting with Jesus had been foreshadowed centuries before in the Song of Songs, the Old Testament’s deeply allegorical love poem. In recognizing Jesus, Mary fulfilled the verse of the Song, which says: “I sought him, but I could not find him” and “My heart leaped up when he spoke” (Song 5:6, NKJV). Not until Jesus spoke her name did she recognize him.

For his part, Jesus seemed to recognize a moment foretold by the Song: “I held him and would not let him go” (3:4); and thus he told Mary not to cling to him.

The Song of Songs was, for the ancient rabbis and the first Christians, an allegory of God’s love for his chosen people. In John’s Gospel, the evangelist was reporting a historical event, but he was presenting it as an image of the risen Lord’s loving encounter with the Church. The Church would “cling” to Jesus only after his ascension, when its members received the Holy Spirit and the gift of the Eucharist.

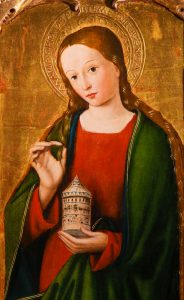

Jesus entrusted Mary with a mission and a message, and she was singular in her testimony. For her role at Jesus’ passion, she earned privileges that were unique in sacred history. In the 13th century, St. Thomas Aquinas noted three of them.

“First,” he said, “she had the privilege of being a prophet because she was worthy enough to see the angels, for a prophet is an intermediary between angels and the people.”

“Secondly,” he added, “she had the dignity or rank of an angel insofar as she looked upon Christ, on whom the angels desire to look.”

And, finally, he said, “she has the office of an apostle; indeed, she was an apostle to the apostles insofar as it was her task to announce Our Lord’s resurrection to the disciples.”

The dignity of a prophet. The rank of an angel. The office of an apostle.

Yet she was unmistakably a woman as she stood for the Church, the beloved of Jesus Christ.