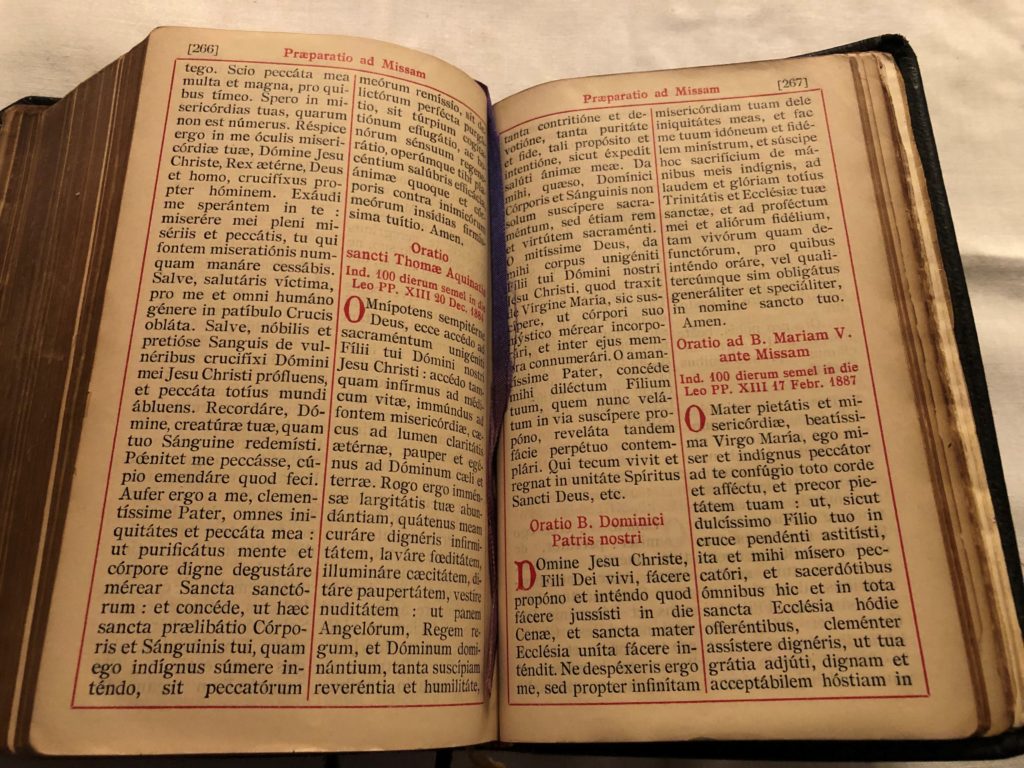

I recently paged through an old Latin breviary that I was given and came across some prayers for a priest to say in anticipation of celebrating the Eucharist. These prayers do not appear in present-day breviaries, nor do I remember being taught them in seminary. Yet they are beautiful, prose-poems.

Looking over them has reminded me of Jesus’ parable of the master of the household who has been trained for the kingdom of heaven and who brings out of his treasure what is new and what is old (Mt 13:52). There is great treasure in old prayers.

One prayer I especially appreciate was given an indulgence of 100 days (the old system of assigning days to partial indulgences or blessings) by Pope Leo XIII on Feb. 17, 1887. My parish church was 1 year old at the time he granted the indulgence, which makes the prayer resonant with the piety and devotions of my ancestors who worshiped here. That’s one practical example of our experience of the communion of the saints.

The prayer is addressed to the Blessed Virgin Mary, who is invoked as “Mother of Piety and Mercy.” The priest says that he is a poor unworthy sinner, who “flies” to Mary with all his heart to ask her assistance.

“As you stood by your Son as He hung upon the cross, stand by me, poor sinner that I am and all the priests of the holy Church as they offer Mass this day. Deign to be with us and help us to worthily offer the Eucharistic sacrifice before the face of the Most Blessed Trinity this day.”

The prayer speaks to my imagination. I confess I can’t say it without thinking of the 1962 song “Stand by Me” by Ben E. King. Perhaps it’s a stretch to link Latin prayers with contemporary lyrics, but poetry is emotion recollected in tranquillity, as are many prayers.

The specific emotion I refer to is the Catholic sense of Mary’s maternal love for us. I imagine her standing by me at the altar, just as many believers imagine her intercession as a personal support and a spiritual presence.

A nun I once knew said that her father, not a typically pious type, would point to his picture of the Sorrowful Mother and say, “There’s my girl.” Perhaps it seems a bit bold to speak with such familiarity, but it’s not at all in tension with the belief that she will be with us and praying for us “at the hour of our death.”

One time a Protestant in El Salvador challenged me about asking for the intercession of the Blessed Virgin Mother. “Do you pray to her?” he asked, as if this was some kind of “reductio ad absurdum” (“reduction to absurdity”).

In implied, “Why would you ask her anything?” I asked him if he ever asked his pastor to pray for him. “Of course, he is a holy man,” he replied.

“Well, you go on asking him for his prayers and I will continue to ask Jesus’ mother to pray for me,” I said. “We’ll see how that works out for us.”

I didn’t mean to depreciate the intercessory prayer of the minister at all. But it is hard for me to understand Christians who believe in praying for one another would think the saints and angels can’t or won’t pray for us. The communion of saints is especially about that mutual relationship in the Lord which includes the solidarity of those in a better position to help those in need.

King’s song says that though “the sky that we look upon should tumble and fall, or the mountains should crumble to the sea,” the solidarity of the loved one will give a sense of security.

“I won’t be afraid,” he sings, “I won’t cry.” I find this especially poignant these days, when it seems like the world is falling apart.

Many generations of priests said the following prayer to the Blessed Mother as they made their way to the altar at the start of Mass: Sicut dulcissimo Filio tuo in cruce pendenti astitisti (“As you stood by your most sweet Son hanging on the cross”).

As with all recited prayer, the unspoken subtext was the mental and emotional state of the priest. Some stepped toward the altar with youthful confidence, others with the careful steps of age or illness. At times the same man could say the prayer with desperate faith or with grateful peace. He could be in crisis, perhaps feeling that, like Jesus, he was on a cross, too. Perhaps he felt the loneliness that suffering provokes in us. Whatever his circumstances, I am convinced that the Blessed Virgin heard his prayer and stood by him invisible and silent as she stood on Calvary.

Words on a yellow page of an old breviary gave me this epiphany. In the sacristy these days, I say to Mary, “As you stood by him, stand by me during this Mass.”