Eritrean Bishop Fikremariam Hagos Tsalim has always encouraged his people to engage in all-night prayer vigils. So the immediate response of Eritrean Catholics to news that the 52-year-old bishop was arrested last month was three nights of unceasing prayer, organized by Eritreans in the United States and Canada.

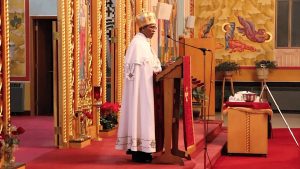

Both Eritrean priests at Sacred Heart Church in the Lincoln Heights area of Los Angeles know Bishop Fikremariam well. They were priests together prior to his 2012 ordination as the first bishop of the newly created Eparchy (Diocese) of Segheneity, Eritrea.

“He was always a very holy, very dedicated young priest,” said Father Tesfaldet Asghedom, pastor of Sacred Heart. “He has so much love for the people.”

That love is needed in Eritrea, which lies across the Red Sea from Saudi Arabia, south of Sudan and north of Ethiopia. The nation has such a reputation for oppression that commentators routinely call it “the North Korea of Africa.”

After its 1993 independence from Ethiopia, President Isaias Afwerki was initially hailed as a democratic reformer. Within a decade, however, he began systematically stripping personal, religious, and political freedoms. He heads the only legal political party and his government controls virtually all institutions. No national elections have been held since he came to office 29 years ago.

People suspected of opposing him often disappear. Young men are conscripted into military service that can be extended indefinitely for ongoing, bloody border wars. So many people flee the country — or die trying — that its bishops have spoken of “depopulation.”

The Catholic Church accounts for about 4% of the 6.1 million population, the majority of them Orthodox Christians and most of the rest Muslims. It is one of just four religious traditions recognized by the state. The U.S. State Department has listed Eritrea as a “country of particular concern” under the Religious Freedom Act for “severe violations of religious freedom.”

Most notoriously, the Eritrean Orthodox Patriarch Antonios was held under house arrest for 15 years until his death in February. He had been outspoken on behalf of religious freedom and the rule of law.

His persecution and death “unites us with the Orthodox, and with those of other religions. Many Protestants are either in jail or are not allowed,” said Father Tesfaldet Tekie Tsada, the associate pastor at Sacred Heart who was also appointed earlier this year by Pope Francis as apostolic visitor to approximately 70,000 Eritrean Catholics throughout the United States and Canada.

Bishop Fikremariam was returning from a somewhat similar visitation among Eritrean refugees in Europe when witnesses reported seeing him forced out of the airport by security agents. Inquiries by Church leaders produced confirmation that the government had detained him, but not the reason or his location.

It was also discovered that two Eritrean Catholic priests — one from the same eparchy and the other a Capuchin from near the Sudanese border — had been imprisoned a few days earlier.

“As far as we know, nobody has had the possibility to engage with him, to visit with him or even to know which jail or prison he is in,” Father Asghedom said.

The Church in Eritrea lacks the diocesan infrastructure with which American Catholics are familiar. Bishops function much like the pastors of very large parishes, Father Asghedom said.

“They are so close to the people, and their resources are very meager,” he said.

Bishop Fikremariam still lived at the parish he had served for years.

A decade after he became bishop “he doesn’t even have his offices built. He is living in this very humble housing around that parish,” Father Asghedom said.

The bishops focus on providing pastoral care but have also spoken publicly about conditions in the nation. In 2014, Bishop Fikremariam with his brother bishops, signed a pastoral letter, “Where is Your Brother?” named for God’s question to Cain about the whereabouts of the brother he murdered. Its social concerns were topped by the number of Eritreans who died trying to reach Europe.

Months earlier, the bishops wrote, “Our country and people were struck by a tragedy that shook even the outside world: the drowning of hundreds of our young countrymen in the waters of the Mediterranean Sea. This was the climax of an odyssey that has been going on for years over mountains, rivers, deserts, and seas at the mercy of criminal human traffickers.”

They wrote of Eritrean migrants who end up dissected for the sale of their organs.

“Given that so many of these stories end in tragedy, is there no other alternative solution?” the bishops asked concerning the migrants.

Their letter didn’t directly castigate the government. It named issues, not responsible parties — but was widely seen as a radical stand for justice. Catholics and non-Catholics read it, despite total state control of news outlets.

“It was like dynamite in the country,” Father Asghedom said. “Many people thought that they were so courageous that the government will do something to them.”

Attempts at sweeping action against the Catholic Church, however, were about five years in coming. Meanwhile, the bishops also spoke out against military policies, most recently Eritrea’s intervention in a civil war in Ethiopia.

In 2019, the government moved to nationalize Catholic schools and health clinics — the latter typically housed in monasteries. Bishop Fikremariam was among those who resisted, particularly concerning the health clinics.

All four Eritrean bishops signed a letter challenging the process that the government used to try to close them and said that patients had been forced out of their beds. A sermon he gave defending the right of the Church to offer health care was recorded — and the two Los Angeles priests speculated that it might have been a reason for his detention three years later.

Many Church-related advocates for Eritreans will not speak on the record, believing it likely to provoke more repression. Christian Solidarity Worldwide — a British organization that advocates for religious freedom across all faiths — is trying to raise awareness of the three abducted Catholics. It links their cases to an ex-patriate Eritrean Orthodox priest and American citizen, Father Kiros Tsegay, who has been imprisoned since he traveled from Florida last year to offer funeral rites for his mother.

“We urge fellow Catholics to pray for the bishop and for all those detained unjustly by the Eritrean regime,” said Kiri Kankhwende, a spokesperson for Christian Solidarity Worldwide. “We also encourage people in the West to call on their governments to raise cases such as the bishop’s detention with the Eritrean government in diplomatic dialogues through direct petitions or through their elected representatives.”

Father Tsada is looking first to prayer, including for diplomatic work by the Vatican. He is also working with other Eritrean priests to send a message to the bishops of the United States and Canada.

The concern of the Church should go beyond its own institutions, to the whole country, he said.

“If we don’t have peace, there is no justice. And that is something we need to have.”