Monday, May 21, marks a new celebration in the Church’s calendar: the memorial of the Blessed Virgin Mary, Mother of the Church.

When the Vatican made the announcement in February, journalists immediately connected the event with Pope Francis’ “last words” before his 2013 election to the papacy.

In an address to the cardinals in conclave, he spoke of the Church as a “fruitful mother,” who lives “by the sweet and comforting joy of evangelizing.”

The new feast is, they concluded, a significant milestone in his papacy — a key to understanding the Holy Father’s motives and actions.

But the roots of the feast go much deeper than that. They reach to the conclusion of the Second Vatican Council in 1965, and then to the great voices in Catholic theology in the mid-20th century, and then to the great Fathers of the early Church, and ultimately to the life of Jesus and the pages of sacred Scripture.

The feast provides a way of understanding not only the current pontificate, but also the long history of salvation.

In announcing the feast, Cardinal Robert Sarah credited the pope’s intention to “encourage the growth of the maternal sense of the Church in the pastors, religious and faithful, as well as a growth of genuine Marian piety.”

As prefect for the Vatican Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments, Cardinal Sarah oversees the Church’s liturgical calendar.

These two notions — the motherhood of the Church and the motherhood of Mary — have been thematically united since the early days of the Church. At the turn of the third century, the African writer Tertullian identified both the Church and Mary as the “New Eve,” mother of all the living.

The doctrine finds an echo in the fourth century in the works of St. Ephrem in Syria and St. Ambrose in Milan. Thus the idea appears universally — in Africa, Syria, Italy and elsewhere — at a very early date.

The great St. Augustine took this idea, stated imprecisely in sermons and hymns, and examined its theological foundations.

The New Testament clearly presents the Church as Christ’s body (Romans 12:4-5; 1 Corinthians 12:27; Ephesians 1:22-23, 3:6, 5:30; Colossians 1:24). If Mary is the mother of Christ, Augustine concluded, she is “clearly the mother of his members, which are we.”

In Scripture, though, Mary’s universal motherhood appears not as a theological notion, but as a role, evident in her actions and in those of her Son, Jesus. Consider, for example:

• The Magi, representing the Gentiles, go in search of the Savior-King and they find “the child with Mary his mother” (Matthew 2:11).

• At Cana, Jesus miraculously renews the wedding festivities — advancing his “hour” of ministry — because his mother interceded with him (John 2:3-4).

• At Calvary Jesus looked to his beloved disciple and said, “Behold your mother,” thus giving her as mother not only to John, but to all of the beloved disciples in the Church (John 19:26-27).

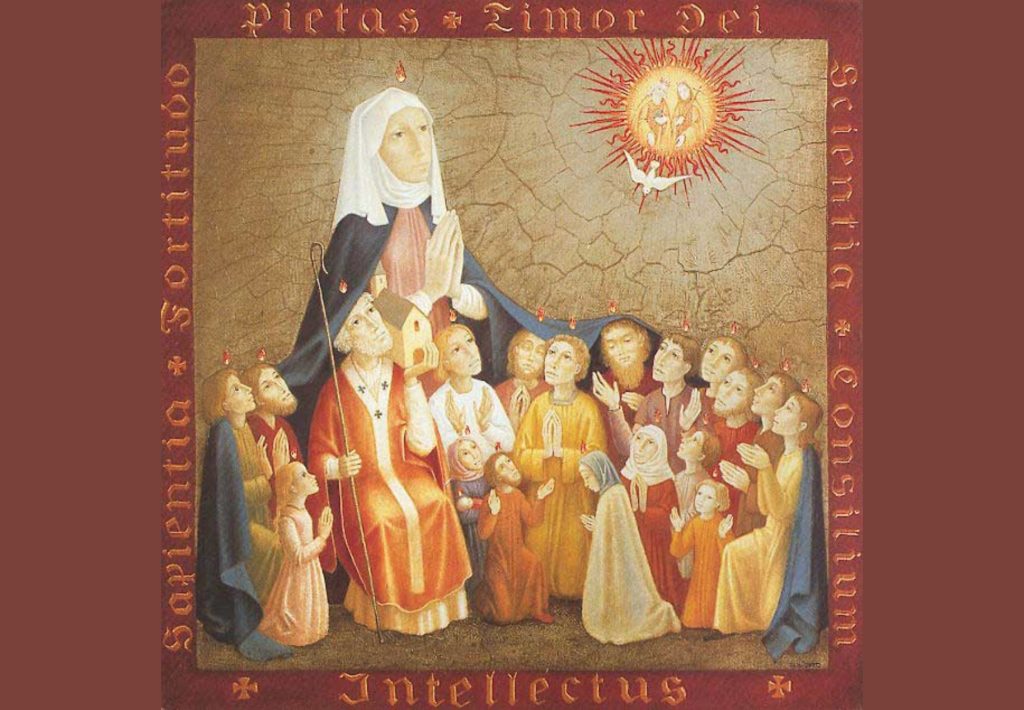

• On the eve of the first Christian Pentecost, Mary is preeminent with the Church, praying for the gift of the Holy Spirit (Acts 1:14).

• In the Book of Revelation, John the Seer presents a mystical vision of a woman in heaven. The woman is at once Mary — the mother of the male child who comes to rule the nations — and the Church, for at the chapter’s end we learn that she has other “offspring” (Revelation 12:27).

• Jesus is “the first-born among many brethren” (Romans 8:29), the firstborn of many siblings in the great assembly, the Church (Hebrews 12:23). If the members of the Church are indeed Jesus’ brothers and sisters — and if they share his home — and if they address his Father as “Our Father” — then they should also look to his mother as their mother, as mother of the Church.

Devotion to Mary

Mary is the mother of all the redeemed. This alone explains the drama of the Council of Ephesus, in A.D. 431. There the bishops of the Church gathered — accompanied by a great throng of ordinary believers — to stop the movement that had arisen against the Church’s longstanding devotion to Mary.

Mary is the Church’s mother, and that is the truth implicit in the construction of the great Gothic cathedrals. The effort often took more than a century in execution. Each was designed to be the “mother church” of its diocese; and most were named for Mary: Notre Dame (Our Lady), La Virgen (The Virgin), Sankt Marien (Holy Mary).

Theological reflection on Mary’s motherhood developed steadily throughout Christian history. In the middle of the 20th century, however, came a great flourishing of scholarship by influential academics and churchmen: Alois Müller, Michael Schmaus, Hugo Rahner, Lucien Deiss and many others. Their study of Mary (Mariology) profoundly influenced the bishops who convened for the Second Vatican Council (1962-65).

At first the Council Fathers planned to issue a document titled “On the Blessed Virgin Mary, Mother of the Church.” But instead they chose to consider Mary’s motherhood in the centerpiece (chapter VIII) of their Dogmatic Constitution on the Church, “Lumen Gentium” (“Light for the Nations”).

Pope Blessed Paul VI called this the “crown and summit” of the document, “an incomparable hymn of praise in honor of Mary.” He noted also that it was the first time a Church Council had “presented such a vast synthesis of the Catholic doctrine regarding the place which the Blessed Mary occupies in the mystery of Christ and of the Church.”

Later, in his remarks at the closing of the Council, the same pope solemnly proclaimed Mary’s veneration under the title “Mother of the Church.”

He was merely recognizing, in an official way, what the Church had always known. He was affirming a title that had long been in use by his papal predecessors. He later invoked the title in his “Credo of the People of God” (1968), and in 1980 his successor St. Pope John Paul II added the title to the Litany of Loreto, a popular prayer.

New life to the Church

The evangelist St. Luke wrote two books in the New Testament: the Gospel that bears his name and the Acts of the Apostles. Each begins with the Virgin Mary awaiting the action of the Holy Spirit (Luke 1:35 and Acts 1:14).

At the launch of the Second Vatican Council, St. Pope John XXIII prayed for a “New Pentecost” to bring new life to the Church. The biblical models clearly show us that such “Pentecostal” moments are always deeply Marian as well.

How fitting, then, that the new memorial of the Blessed Virgin Mary, Mother of the Church, takes place the day after Pentecost.

With this feast, Pope Francis continues the work of recent popes and renews the climactic teaching of the Second Vatican Council.

Why now? The pope has repeatedly worried aloud about divisions in the Church — Christ’s body torn by interests that are primarily earthly, selfish or factional, and grossly political.

Well, no force on earth is more unifying than motherhood. There’s a meme that’s popular in social media, usually posted by moms: “A mother’s prayer is that her children will love each other long after she is gone to heaven.”

Can we doubt that this is the urgent, ardent prayer of Mary, mother of the Church?

We should mark the new feast in a way that would please her — perhaps by a commitment to charity in speech, especially when we talk about the Church and the clergy. We could mark the feast well by renouncing gossip about the Church, the parish or the pastor.

It’s not a holy day of obligation, but we might make the effort to go to Mass anyway.

And we should celebrate with all the usual trimmings of our festivals — special music, food and a bit of wine perhaps. Mother would want it that way.

Mike Aquilina is a contributing editor of Angelus News and the author of more than 40 books, including “Keeping Mary Close: Devotion to Our Lady through the Ages” (Servant, $14).

Interested in more? Subscribe to Angelus News to get daily articles sent to your inbox.