I sail a sea comprised solely of sailors. To my port and starboard stand 200 other swaying souls in the concert venue, all sporting captain hats and with fake mustaches plastered above lips murmuring along to “Lido Shuffle.”

My own faux stache, awkwardly draped over my real mustache, has peeled itself off somewhere in the journey between “Baker Street” and “Africa.” The hat stays on, and I cling to it for dear life as the chorus and crowd ascend to that barbaric yawp of “whoaOhOhOhOoOo.” It is at that moment I finally understand the charismatics.

Forgive the poetry, but then how can you not be romantic about Yacht Rock? This is the genre of Mustache Harbor, the cover band my family took in last month in San Francisco. ‘Yacht Rock’ is the colloquial catchall for the late ’70s- early ’80s Los Angeles soft rock scene, throwing diverse acts like Steely Dan, The Doobie Brothers, Toto, and Kenny Loggins under the same beach umbrella. It’s less a genre than vibe, the type of music you want in the background as you’re three sheets to the wind in either capacity.

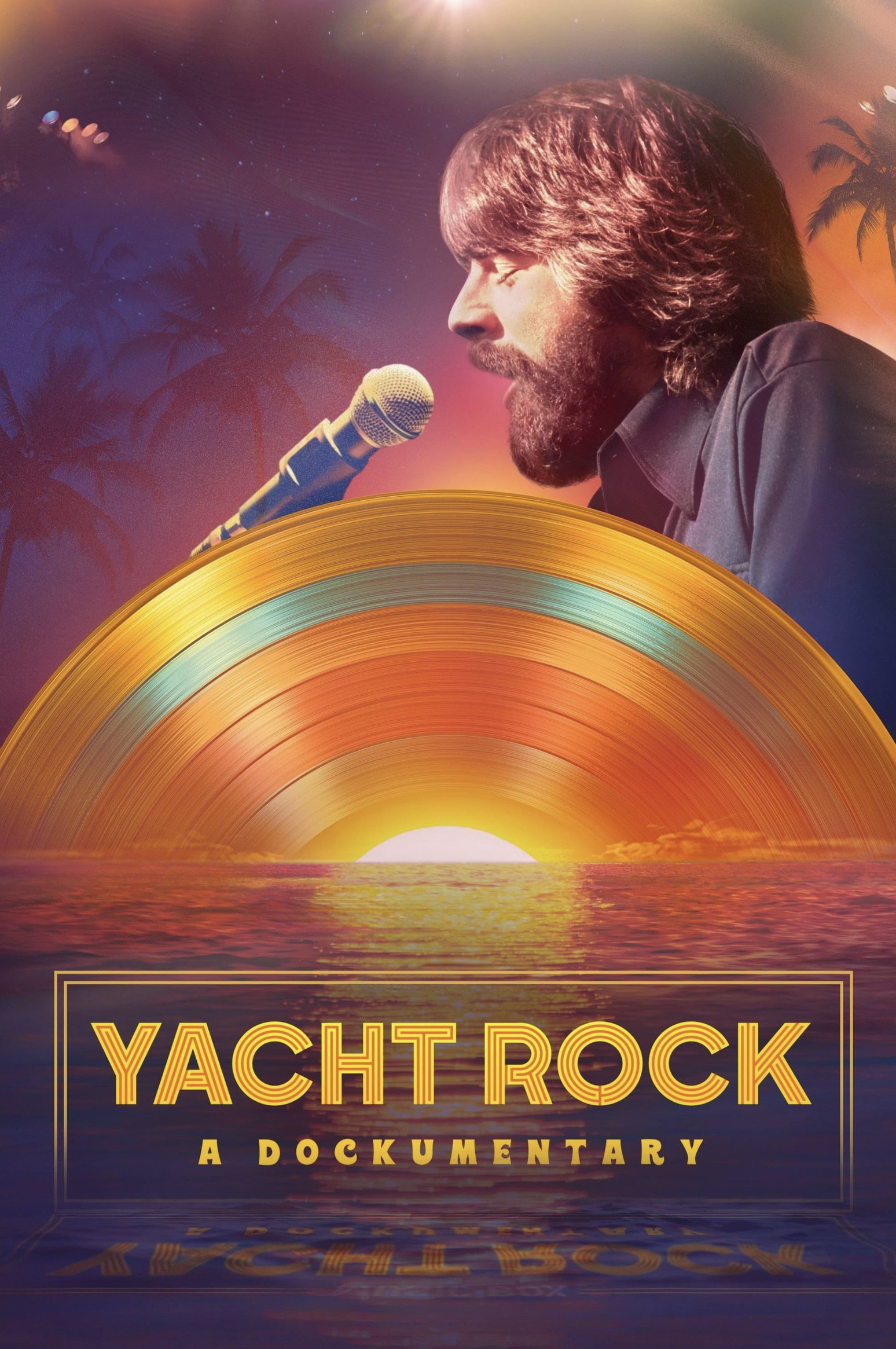

HBO released a documentary on the subject the day I returned from that trip, playfully titled “Yacht Rock: A Dockumentary.” As a Catholic, I don’t believe in coincidence, preferring to take the universe and its indifference personally. The flipside of that coin is I must accept the positive portents as well, which means I’ll have to dig through Yacht Rock and take you with me.

The first rule of Yacht Club is that Yacht Rock doesn’t exist. The name was foisted upon a loose fraternity of Los Angeles-based musicians in the 1970s by a loose fraternity of Los Angeles-based comedians in the early 2000s, who pieced together the family tree of how Steely Dan session players went on to start bands of their own with similar Smooth Jazz stylings. The comedians started their own popular YouTube sketch series on their invented genre, which soon absorbed the acts themselves as they woke up part of a movement.

The musicians interviewed for the film have a range of responses. Michael McDonald finds some amusement in it, while Donad Fagen of Steely Dan finds four letters. The only thing they agree upon is that they didn’t see themselves as Yacht Rockers in the moment. In “The Last Days of Disco,” Whit Stillman’s film about a concurrent genre, a yuppie protests his classification by saying since no one personally identifies as a yuppie, the group can’t possibly exist. By such a litmus Yacht Rock is post hoc, for what union can exist without due-paying members?

Part of their hesitation lies in wondering if they’re the butt of the joke. Between interviews with the musicians are talking head segments with critics and cultural commentators, who are all well-meaning Los Feliz types who have long lost track of the line between irony and sincerity. I am on the brink of my 20s but still cower in fear when high-schoolers laugh in my vicinity; I suspect the same dynamic is at play. When a man in a Ninja Turtles T-shirt insists you’re cool, you can’t help but speculate what curve he’s grading on.

Somewhere in the goofy name and ironic appreciation and fake mustaches, their actual artistry is lost in the shuffle. The documentary does them justice there, demonstrating their chops and how much hard work it takes to create soft rock, how much effort goes into sounding easygoing.

The band Toto, for example, was so proficient at it that they became the session house band for hundreds of albums by other artists, releasing just 14 under their own name (Michael Jackson’s “Thriller” is largely their doing). When a fellow songwriter asked Michael McDonald how he wrote so many hits, McDonald told him he studied Bach’s chord progressions, insisting it was really all right there.

If there is a connective tissue in Yacht Rock, or perhaps even a guardian angel, it’s McDonald. He was generous with his time and talent, his dulcet tones haunting the background of Steely Dan, Christopher Cross, and Kenny Loggins songs. Moreover, McDonald is a sort of avatar for the whole scene’s cheery professionalism. The men here are LA survivors: They took nothing personal and just kept showing up to work, and seem surprised they’re even remembered. McDonald’s midwestern ethos set the tone more than any yacht-riding, champagne-popping lifestyle. He’s from Missouri: paddle steamers seem more his speed anyway.

There is a spiritual undercurrent in Yacht Rock, which may be the source of this buoyancy. McDonald is essentially a Gospel singer with Top 40 aspirations: His work with The Doobie Brothers (like “Takin’ It to the Streets”) is a more rousing call to action than “Onward Christian Soldiers.” One of my own personal favorite Yacht Rock songs is his duet with James Ingram, “Yah Mo B There,” the best argument that you of course can talk about God in pop music — just so long as you spell his name creatively.

It should also be noted that Yacht Rock duo Seals & Croft, with session work by Toto, released the only pro-life rock album on record, 1974’s “Unborn Child,” the merits of which I cannot attest to out of professional laziness. Seals & Croft and some members of Toto were practicing members of the Baháʼí Faith, the pan monotheistic religion. In an industry where Catholics are few and accomplish less, I find myself amiable to the Baháʼí conspiracy. For those looking for it, perhaps they are the light side of the Force to counter Scientology.

Two days after watching the documentary, about four days since arriving home, and perhaps a full week since the Mustache Harbor concert, I found my missing mustache. It had attached itself to the left elbow of my flannel, a groovy little caterpillar who I was surprised to find had never left me at all.