Jean-Henri Fabre’s “Book of Insects” is a 1921 classic, with beautiful, tissue-paper-protected color plates by .

If you can get your hands on a copy (I checked mine out from the L.A. Public Library), you’ll discover a whole wondrous world. The glow worm, the grub, the locust, the mason-wasp — all your favorite insect pals are here.

Fabre (1823-1915) was an ardent Catholic with a deep sense of God’s design. In the opening chapter, he tells of coming upon the nest as a boy of a “lovely bird” that held six eggs of a “magnificent azure blue, very bright.” Thinking to carry one home as a trophy, he “walked carefully home, carrying my blue egg on a bed of moss.”

He met a priest.

“Ah,” said he. “A Saxicola’s egg. Where did you get it?”

I told him the whole story. “I shall go back for the others,” I said, “when the young birds have got their quill-feathers.”

“Oh, but you mustn’t do that!” cried the priest. “You mustn’t be so cruel as to rob the poor mother of all her little birds. Be a good boy, now, and promise not to touch the nest.”

“From the conversation I learnt two things: first, that robbing birds’ nests is cruel, and secondly, that birds and beasts have names just like ourselves.”

Fabre was self-taught and said he received only three lessons in science his whole life: one in economic zoology (the village priest and the Saxicola egg); one in chemistry, during which he caused an explosion that nearly blinded the class; and one in anatomy, in which French naturalist Alfred Moquin-Tandon showed him the structure of a snail in a plate of water.

He taught chemistry and geometry for a living, trained himself in physics and botany as well, and on his own learned Latin and Greek. From Wikipedia: “In one of Fabre’s most famous experiments, he arranged Pine Processionary caterpillars to form a continuous loop around the edge of a pot. As each caterpillar instinctively followed the silken trail of the caterpillars in front of it, the group moved around in a circle for seven days.”

That’s the kind of useful, fascinating thing people did before the advent of television.

Tolstoy could have been thinking of Fabre when he said, “There is nothing in the world that should not be expressed in such a way that an affectionate 7-year-old boy can not see and understand it.”

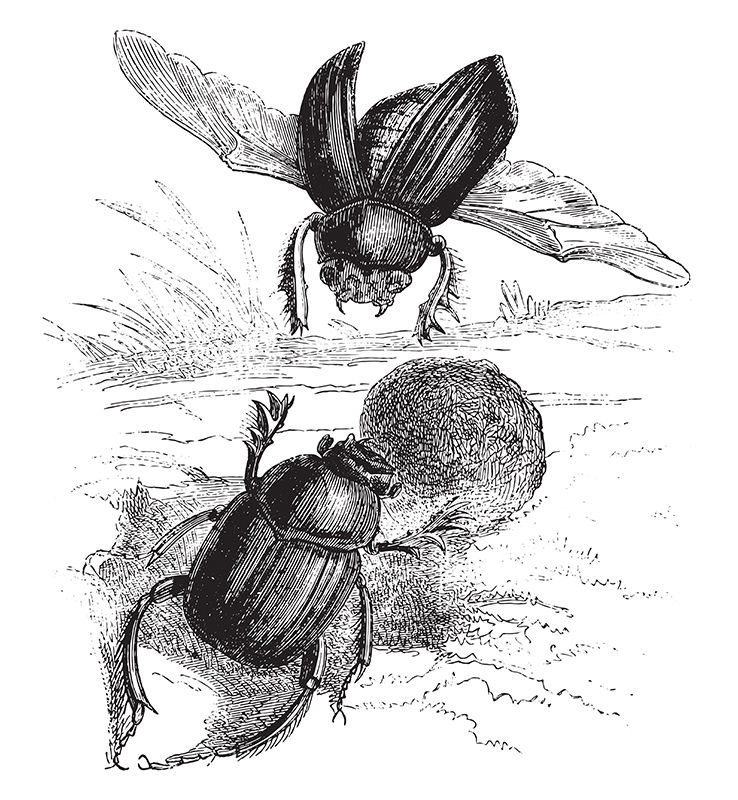

The Sacred Beetle, for example, rolls a giant ball of food from “his sweepings from the roads and fields.”

“Sometimes a thief comes flying up, knocks over the owner of the ball and perches himself on top of it. With his fore-legs crossed over his breast, ready to hit out, he awaits events. If the owner raises himself to seize his ball, the robber gives him a blow that stretches him on his back. Then the owner gets up and shakes the ball till it begins rolling and perhaps the thief falls off. A wrestling-match follows.

“The two beetles grapple with one another: their legs lock and unlock, their joints intertwine their horny armor clashes and grates with the rasping sound of metal under a file. The one who is successful climbs to the top of the ball and after two or three attempts to dislodge him the defeated Scarab goes off to make himself a new pellet. I have sometimes seen a third beetle appear, and rob the robber.”

He learned that the insect world is full of skilled surgeons, expert anesthesiologists, master mathematicians, martyrs, Christ-figures and criminals.

“The chilly, bare-skinned Psyche [Caterpillar] builds himself a portable shelter, a traveling cottage which the owner never leaves until he becomes a moth ... a suit of clothes out of sticks. And since this would be a regular hair-shirt to a skin so delicate as his, he puts in a thick lining of silk.”

“The young Mantis finds it necessary to wear an overall when coming into the world. … The creature … appears in swaddling-clothes and has the shape of a boat.” Later we learn that “the Mantis, I fear, has no heart. She eats her husband and deserts her children.”

“Four years of hard work in the darkness, and a month of delight in the sun — such is the Cicada’s life. We must not blame him for the noisy triumph of his song.”

He could have been thinking of his own life. After 40 years of “desperate struggle,” Fabre’s fondest dream was realized. He was able to buy a harmas, the name in Provence for “an untilled, pebbly expanse where any plant but thyme can grow.” There, the “Homer of the Insect World” as he was sometimes called, lived out his days, surrounded by his beloved wasps, beetles and plants.

“After 87 years of thought and observation,” he wrote at the last, “I say not merely that I believe in God — I can even say that I see him.”

Heather King is a blogger, speaker and the author of several books.