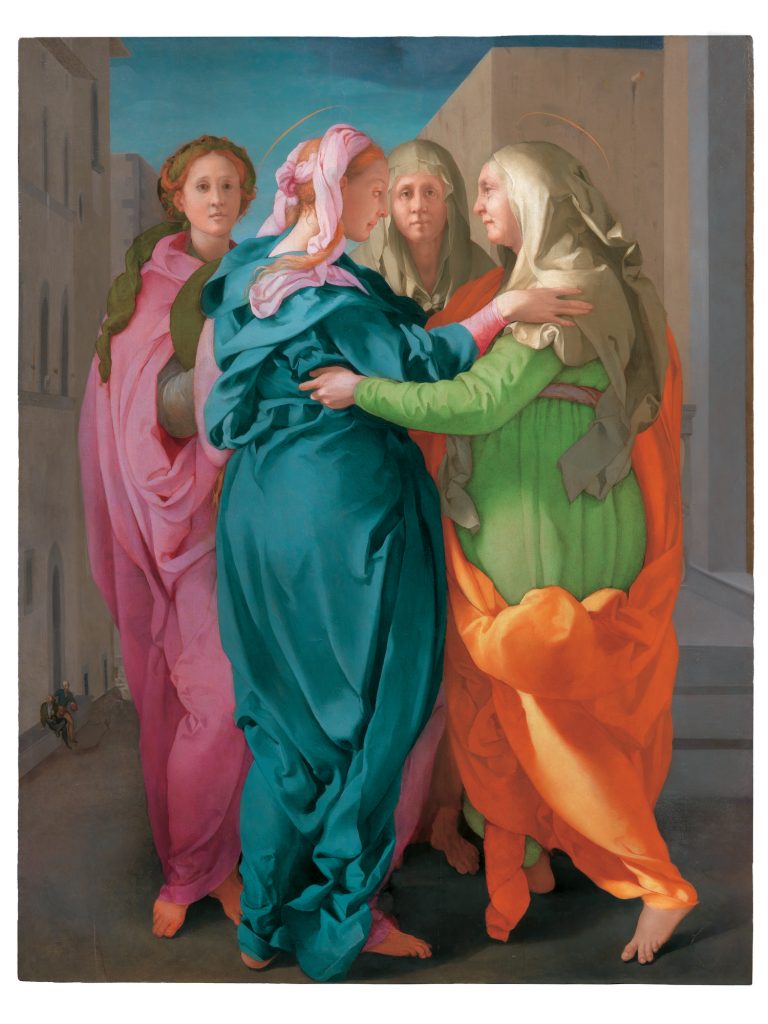

“Is it true, Prince, that you once said: ‘It is beauty that will save the world?’” Dostoyevsky’s famous quote from “The Idiot” naturally comes to mind as one stares at Jacopo da Pontormo’s “Visitation,” one of the most visionary paintings from the Italian Renaissance.

The “Visitation’s” extraordinary features seem perfectly designed to convey the essence of a miracle, an extraordinary event manifesting the appearance of the divine within the threads of ordinary life.

The altarpiece represents the encounter between St. Elizabeth and the Virgin Mary recounted in the Gospels. Mary reaches out tenderly to embrace her older relative. The two women lock eyes and share in the extraordinary event of their pregnancies.

Elizabeth, who may be as old as eighty, is pregnant with John the Baptist. In the Gospel, the child exults in his mother’s womb as he senses the presence of Jesus.

The “Visitation” has never traveled outside of Italy before, having been for most of its life kept in the Church of Carmignano, a small village just a few miles outside of Florence.

Pontormo’s “Visitation” has now crossed the ocean to join its artistic cousin (and one of the Getty’s most precious possessions), Pontormo’s “Portrait of a Halberdier,” for a focused exhibit centering on the legacy of this famously unconventional Renaissance artist titled “Pontormo: Miraculous Encounters,” which began Feb. 2 and continues until April 28.

A disciple of Andrea del Sarto, admired by Michelangelo and hailed by Rafael as one of the most promising talents of his generation, Pontormo was known for being a solitary, almost reclusive man.

His art is permeated by deep religious reflection. Davide Gasparotto, the Getty’s senior curator of paintings and a co-organizer of the exhibit, defines him as “one of the greatest painters and draughtsmen who ever lived,” a judgment that was shared by many of Pontormo’s contemporaries.

"Portrait of a Young Man in a Red Cap” (Carlo Neroni), by Pontormo, 1530. (SHEPHERD CONSERVATION, LONDON)

Besides the “Visitation” and the “Portrait of a Halberdier,” the exhibit features another portrait of a man in military garb by Pontormo (“Portrait of a Young Man in a Red Cap”) and four drawings. Three of these are studies for the “Halberdier,” the “Visitation” and the soldier portrait.

The fourth is a self-portrait, a study for Pontormo’s masterpiece, the “Deposition of Christ,” in which the painter imagined himself in the role of Nicodemus, a disciple of Jesus — a sculptor, according to medieval and Renaissance traditions, who took care of the Savior’s dead body.

Three more pieces complete the exhibition. An engraving by Albrecht Dürer (whose figural composition seems to have influenced Pontormo’s “Visitation”), an edition of Vasari’s biography of Pontormo (from his “Lives of the Artists”), and “Pygmalion,” a magnificent painting by Pontormo’s foremost student and pupil, Agnolo Bronzino.

In Renaissance Florence, no respectable woman would have been allowed outdoors without an attendant. Pontormo follows in the tradition of depicting Mary and Elizabeth each accompanied by a handmaid, but innovates in the “Visitation” by having the two servants stare straight into the spectator’s eye, as if to invite the viewer to share in the miraculous event.

The four figures’ faces and eyes line up in a seemingly straight line, while the positioning of their feet is nearly rectangular.

The two maids are roughly of the same age as their ladies, and they resemble them. Mary’s handmaid is dressed in hot pink, the same color as Mary’s headband. Elizabeth’s veil is in the same color as the one worn by her attendant.

The effect is that the figures seem to appear from multiple perspectives, as if Mary and Elizabeth had turned toward the viewer themselves. The divine look of Mary thus seems to repose on the viewer precisely as it reposes on Elizabeth.

Although the painting is permeated with an atmosphere of joy, the “Visitation” was completed at a time of great crisis. From 1529 to 1530, Florence was besieged by the forces of the Holy Roman Emperor, who wished to abolish the newly established republican government and return the city to the control of the Medici family.

It is no coincidence that the other portraits exhibited in the show, painted in the same years as the “Visitation,” depict young men at arms: as the “Visitation” was being created, young Florentine nobles were busy defending their newly acquired freedom against the power of the Medici.

In Pontormo’s “Visitation,” God is quite literally in the details. Following the tradition of Giotto and early Florentine masters (and unlike the account of the Gospels), the scene of Mary and Elizabeth’s encounter is set outdoors.

And unlike in earlier paintings of Pontormo’s time, the buildings in the background look very little like a village in Judaea and very much like Renaissance Florence.

Look at the lower left side of the painting. Two gentlemen are sitting idly outside (one seems to be drinking, the other holds his hat). They are dressed like men from Pontormo’s time. Just above the two men, a woman is hanging clothes from a window: a scene of everyday life in Florence.

Beyond the two tiny figures a donkey is seen peering from behind a wall, about to turn the corner and enter the frame.

“Fear not, O daughter of Zion; Behold, your king is coming, sitting on the foal of a donkey,” recites the biblical prophecy of Zechariah. Mary traditionally rides a donkey on her journey from Nazareth to Bethlehem; Jesus sits on a donkey at the time of his momentous entrance into Jerusalem, the day of his consecration as Messiah and a prelude to his crucifixion.

In Pontormo’s view, the “Visitation” is not a fairy tale, nor is it merely the commemoration of an event that took place centuries ago: Salvation is still happening now. Humanity is still being visited now. The immense compassion of God has not ceased to be; the divine is still entering our world to draw life from barren wombs.

This is why Elizabeth is made to look so much older than in other paintings of this subject. Her impossibly old age emphasizes the extraordinary power of God. The look of Mary still mediates the divine power of her Son, communicating life to those who are unable to give life, love to those whose hearts are made of stone.

The “Visitation” is the moment in which the incarnation brings its first fruits. According to tradition, John the Baptist was cleansed of original sin at the moment he felt the approaching presence of the Messiah.

But the Divine enters the world disguised under ordinary features. The Savior does not come riding a horse or a chariot of fire, but on the back of a donkey. His incarnation will surprisingly appear through the poverty of the human nature, so much so that his miraculous epiphanies can easily be missed. The tiny men in the left corner are not looking at the scene in the foreground.

His self-portrait in the Getty exhibit, a preparatory sketch for the “Deposition of Christ,” shows us a man not merely contemplating, but sharing in the suffering of Christ. In the “Deposition,” Pontormo included himself in the supreme act of Christ’s earthly mission, precisely as the “Visitation” invites viewers to join in the joy for the always current event of his incarnation.

SPECIAL OFFER! 44 issues of Angelus for just $9.95! Get the finest in Catholic journalism with first-rate analysis of the events and trends shaping the Church and the world, plus the practical advice from the world’s best spiritual writers on prayer and Catholic living, along with great features about Catholic life in Los Angeles. Subscribe now!