“In our culture,” writes Ross Douthat early in his new book, “the word decadence is used promiscuously but rarely precisely which, of course, is part of its cachet and charm.” Douthat uses the term promiscuously in “The Decadent Society: How We Became the Victims of Our Own Success” (Simon & Schuster, $24), but he does manage some measure of precision, as much as can be expected when attempting to diagnose societal ills.

Douthat, a columnist for The New York Times, is a deft writer unafraid of ambition, which is requisite for the scope of his project.

In our modern society, he notes, “it remains a central cultural assumption that unexplored frontiers and fresh discoveries and new worlds to conquer are not just desirable but the very point of life.” We live to spend more, accumulate more, be more.

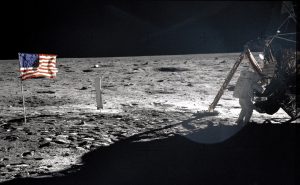

Those ambitions cause real problems. According to Douthat, the “end of the space age” has “coincided with a turning inward in the developed world, a crisis of confidence and an ebb of optimism and a loss of faith in institutions, a shift toward therapeutic philosophies and technologies of simulation, an abandonment of both ideological ambition and religious hope.” The more we have, the more we long for something beyond the material.

Such longing isn’t a new story, of course, but Douthat sees related decadence as a particularly modern disease. Following the work of cultural critic Jacques Barzun, Douthat explains that although decadence is often associated with “decay and decline,” decadence doesn’t always portend “a collapse.” Sometimes the rich get richer, and richer, and richer.

What offers precision to Douthat’s discussion of decadence is his focus on stagnation: our intellectual, cultural, religious, and technological stasis. The latter might be surprising: Aren’t we surrounded by the digital world? Isn’t everything more accessible, faster, more fluid now?

Douthat doesn’t want us to be distracted by shine over substance: The internet and other digital innovations are “still a blip compared with the cascade of changes between 1870 and 1970, and a letdown compared with what we dreamed about not so very long ago.”

Douthat sums it up in a pithy observation: “We used to go to the moon; now we make movies about space — amazing movies with completely convincing special effects — in which small fortunes are spent to make it seem like we’ve left earth behind.”

I was initially skeptical of that assertion — its parallel structure feels a bit too perfect — but Douthat manages to convince me by the end of the book that he is on to something.

A Catholic convert, one of Douthat’s previous books, “Bad Religion,” laments the “slow-motion collapse of traditional Christinaity and the rise of a variety of destructive psuedo-Christianties in its place.” “The Decadent Society” is a less overtly religious work, but it is suffused with a Catholic sense: a curious yet authentic mixture of concern and optimism. We are stuck in a bad place, Douthat argues, but there is hope.

Such hope can’t happen without being honest about our modern situation. He identifies the “problem of mediocrity”: how the digital world “pressures creators to make things clickable, browsable, capable of holding attention briefly, but always with the understanding that the reader or watcher will swiftly move on to the next hyperlink, the next video, the next tweet or status update or Instagram pic.”

While it might seem an exaggeration to credit the internet with such power, unfortunately for a part of our world, their digital life is emblematic of how they treat people off-screen. It would be naive to assume that we can be superficial online, and then become empathetic offline.

Douthat is correct that “the internet, in effect, is a surveillance state: the virtual fulfillment of Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon, where Big Brother doesn’t have to watch everyone because everyone is always watching everybody else.”

In many ways, we have chosen a stagnation of convenience: It is easier to live within one’s ideology, to critique those across the political aisle (or even across the street), rather than to do the messy work of real dialogue.

Perhaps the strongest and most nuanced part of his book is the observation that critics of decadence need “to give decadence its due,” and that “starts with the reality that complaining about decadence is, almost by definition, a luxury good — a feature of societies where the mail is delivered, the trains and planes are running on time, the crime rate is relatively low, and there are plenty of entertainments at your fingertips.”

Our decadent discontent is not on par with suffering of other eras, but that doesn’t mean we should accept our moral stagnation.

Douthat returns to the space age as he concludes his analysis. Channeling the work of historian Kendrick Oliver — who argued that the American space program was sustained by a sense of religious aspiration, and when that religious verve disappeared, so did the will to explore — Douthat thinks we must look elsewhere to escape stagnation.

“I suspect that a truly globalized civilization cannot help tending toward decadence so long as it remains earthbound, so long as there is no hope of finding actual new worlds to leap toward, conquer, or explore,” Douthat claims.

Our symptoms, “the turn toward simulations and virtual realities; the declining birth-rates: the sense of repetition, stagnation, and futility” are “connected on a deep level to the post-Apollo mission sense that such a hope does not exist.”

Here a more pointedly Catholic solution, or perhaps a Catholic vision, would feel more effective. Douthat’s return to the space race feels steeped in cultural nostalgia rather than theology. Sure, let’s keep looking to the heavens for inspiration, but I suspect the answer to what ails us resides less in the stars, and more within our souls.