When it comes to Flannery O’Connor, “You either get it or you don’t — and if you don’t, then don’t go to the carnival.” While this statement from an interviewee in the upcoming documentary “Flannery” might seem harsh, it is true that O’Connor’s writing strikes many as off-putting.

But as one might suspect, there’s more to her sinister narratives than meets the eye.

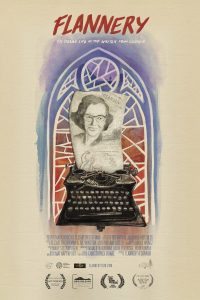

Written, directed, and produced by Elizabeth Coffman and Mark Bosco, “Flannery: The Storied Life of the Writer from Georgia,” explores what made O’Connor (1925–1964) the renowned author she is today. Premiered at the Hot Springs Documentary Film Festival last October, the documentary won the 2019 Library of Congress / Lavine / Ken Burns Prize for Film and has been recognized at several other festivals since then.

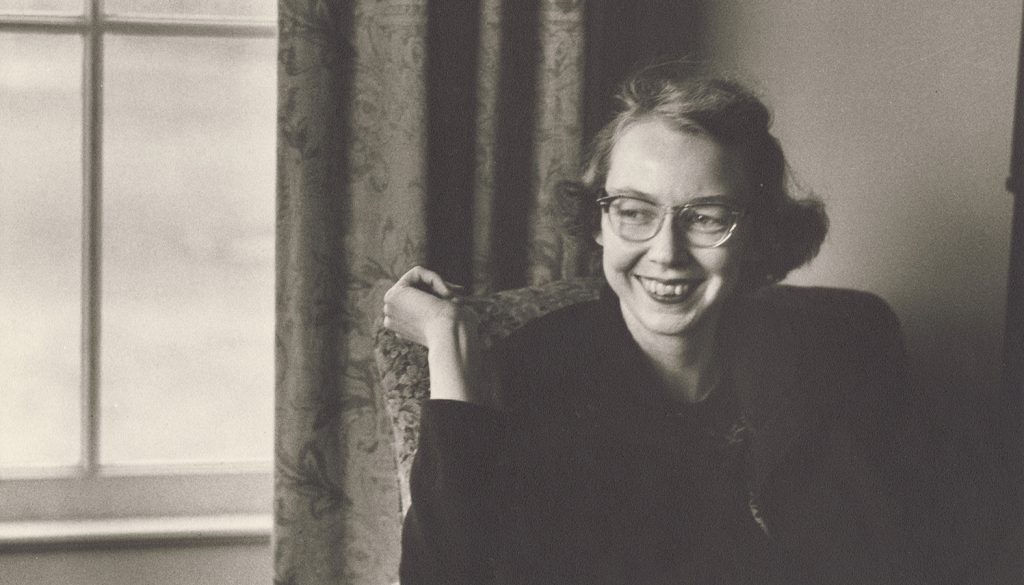

O’Connor’s work has received renewed attention lately, especially when it comes to the racist attitudes found in some of her writings. This film adds another layer to that conversation but incorporates a broader one as well. In 97 minutes, “Flannery” integrates a series of photos, footage, and interviews to do more than just illustrate the controversial author’s life and work: It shows how her writing speaks directly to not just the South, not just segregated America, but to today’s troubled world.

Few, if any, of O’Connor’s compositions would make a soothing bedtime story. Arguably her most famous short story, “A Good Man is Hard to Find,” involves a car crash, mass murder, and an existential conversation at gunpoint. Suffice it to say that her writing is not for the faint of heart.

How could O’Connor write such disturbing tales? After all, as comedian Conan O’Brien observes in the film, one might more readily expect the author to be an old, embittered drunk than a young, intensely Catholic woman.

The intriguing answer the documentary offers is that she could not have done otherwise. While others might prefer to overlook the ugliness in the world, O’Connor refused. One might argue that she did not have the luxury to do so. Her relatively happy childhood was cut short by the death of her father, and she subsequently suffered illness, heartbreak, and criticism throughout her life. What’s more, the world around her reeked with discrimination, violence, and death, themes that she captured with biting accuracy (and often witty mockery) in her writing.

O’Connor was certainly no stranger to tragedy, but as one interviewee puts it, she was “least afraid to look at the darkness.” What carried her through tragedy, the film reveals, was her faith. Indeed, O’Connor’s Catholicism was as much a part of her identity as her writing, or even more so, since the former fueled the latter.

Born into one of the few Catholic families of a mostly Protestant town, practicing her outsider faith was woven into the fabric of her heritage and daily life. But hers was anything but a blind faith. Interviewees describe her profound prayer journal reflections, daily Mass attendance, and earnest questions to spiritual directors about tackling issues of race and immorality in her writing. In this way, her faith never dwelt separately from her work but rather always shaped it.

Through that dialectic between faith and suffering, her work reveals a powerful truth: that God is present even — and perhaps especially — in the darkest moments of life.

Throughout the film, our interviewees help peel back the layers of O’Connor’s writing to expose this reality. In her controversial novel “Wise Blood,” one of them notes, the itinerant preacher protagonist announces a gospel of “truth without Christ,” apparently determined to construct his own morality, only to prove that one can never escape from God. And in “A Good Man is Hard to Find,” it is when the protagonist is on the brink of death that she realizes her kinship as a fellow human with a ruthless criminal.

O’Connor’s manner of delivering her theology might be shocking, but the theology itself is not new. It is worth noting (as the documentary in fact does) that she drew inspiration from medieval Christian art, which often portrays the grotesque alongside the sublime. What’s more, viewers will find that just behind O’Connor’s writing desk, as in so many other Catholic homes, hangs a crucifix, an image that at once recalls the blackest crime in human history and the most perfect revelation of God’s love.

One might venture to describe O’Connor’s work as a kind of new medieval art, or even a metaphorical crucifixion scene: In her fiction, one encounters an intersection between the earthly and the heavenly. In other words, it is through her disconcerting tales that she points to the wonder of a God who pursues his people tirelessly, even to the scum of the earth.

That ability, combined with her knack for imagery and humor, sustains O’Connor’s legacy as a remarkable writer. Like almost no other author, this documentary shows, she can expose the ugliness of sin, poke fun at its stupidity, and expose its futility before the power of grace.

O’Connor once remarked that she wrote for those who say that God is dead. Perhaps she found that walking alongside such readers on their despondent path was the surest way to lead them to the consolation of truth. “Flannery” draws viewers into the heart of that terrifying yet bold path that O’Connor tread, both in the lives of her characters and in her own life.

Although her approach need not (and maybe should not) be a universal one, it offers a healthy reminder of the importance of acknowledging the evil that afflicts our world. And in confronting that evil, as O’Connor invites readers to do, we can experience that grace is active even in the darkness.

“Flannery” is available to stream on various virtual cinemas. More information is available at www.flanneryfilm.com.