How long has Dion DiMucci been making music? Here’s how long: When he sang “I’d make love to you” in the song “Can’t We Be Sweethearts,” he wasn’t referring to anything R-rated any more than Laurence Olivier was when he told Joan Fontaine in the film “Rebecca” that he “should be making violent love to [her] behind a palm tree.”

Dion, in other words, was simply promising his sweetheart lots of romance — with “lovin’ kisses too”!

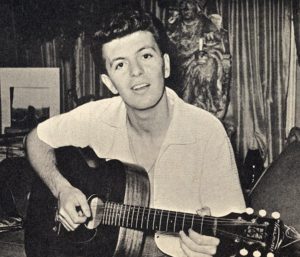

The year was 1963, the album “Donna the Prima Donna.” And Dion was all of 24 years old. Yet he was already a rock ’n’ roll veteran, with 16 top-40 singles to his name (or his and the name of his doo-wop backing group, the Belmonts) dating back to 1958.

The biggest — “A Teenager in Love,” “Lovers Who Wander,” “The Wanderer,” “Runaround Sue,” “Ruby Baby” — would eventually propel him into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame (and, what’s arguably cooler, find him rubbing shoulders with Tony Curtis and Oscar Wilde on the cover of the Beatles’ “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” album).

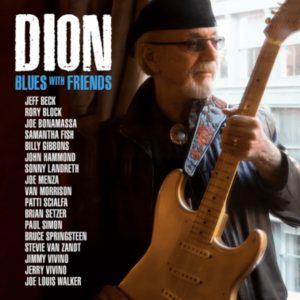

He’s in the news these days because of his new album, “Blues with Friends,” his 33rd solo recording (not counting live discs and compilations) and his first for Keeping the Blues Alive, a label launched by the blues guitarist Joe Bonamassa.

You could call the album a comeback, except that Dion has never really gone away. Leaving aside the hiatuses between 1963’s “Ruby Baby,” 1968’s “Dion,” 1993’s “Rock n’ Roll Christmas,” and 2000’s “Déjà Nu,” he hasn’t gone more than three years without releasing new music.

And, incredible as it may seem given his many accomplishments and the fact that he’ll turn 81 in July, “Blues with Friends” might be the best long player of his career.

His switchblade-tenor voice evinces minimal wear and tear, and 12 of the 14 compositions are new. They haven’t come out of nowhere: His last four albums—Bronx in Blue, Son of Skip James, Tank Full of Blues, New York Is My Home—were blues efforts too. But the new songs are tougher, sharper, and sometimes even sweeter than their recent antecedents.

And although the majority are blues through and through, they’re spelled by haunted roots exercises ranging from yearning folk to nightclub jazz that open windows through which refreshing cross breezes flow.

Even without the tasty contributions of the guest guitarists (Bonamassa, Jeff Beck, Joe Louis Walker, John Hammond, Sonny Landreth, ZZ Top’s Billy Gibbons, Stray Cats’ Brian Setzer) and singers (Paul Simon, Van Morrison, Rory Block, Patti Scialfa), “Blues with Friends” would have listeners wearing out the “repeat” buttons on their playback devices of choice.

As for the two vintage copyrights, “Kickin’ Child” (which Dion originally recorded in 1965) and “Hymn to Him” (1986), they’ve never sounded better.

“Songs are never finished,” Dion says of the latter in the album’s press kit. “I kept hearing this with Patti’s voice, so I asked her to help me remake the song.” Scialfa’s singing plus an impromptu guitar solo from her husband, Bruce Springsteen, made the song, in Dion’s words, “something sublime.”

As its title suggests, “Hymn to Him” is a gospel song. “Come to Him through the darkness,” Dion sings, “come to Him through the rain, / walk with him from misfortune, / walk with Him from the pain.”

It’s the album’s last song and, as such, a culmination, the inevitable last stop on a journey foreshadowed by the “train bound for heaven” that Dion boards 11 songs earlier on the loping “Uptown Number 7” and promises never to disembark.

It’s a metaphor with particular meaning in Dion’s case. The main reason for his dry spell circa 1963-1968 is that the heroin habit that he’d begun nursing as a teenager in the Bronx had finally overtaken him, all but undoing his music, his marriage, and anything else of value that he’d worked to amass.

Eventually, to make short a long and moving story that Dion himself has told many times, he got clean (with the help of his wife and a 12-step program) and did in fact board the Gospel Train.

The best-known song of what’s sometimes called his “mature period” — his hit rendition of Dick Holler’s paean to assassinated emancipators (real or perceived), “Abraham, Martin and John” — followed shortly thereafter and reflected his newfound gravitas. But it was his two self-penned confessions-of-an-ex-junkie numbers “Daddy Rollin’ (In Your Arms)” and “Your Own Backyard” that laid bare his soul.

By 1980, after a decade of earnest but commercially unsuccessful albums, he’d begun taking his Christian faith especially seriously, immersing himself in the evangelical subculture and reinventing himself as a born-again singer-songwriter. In 1984, the third of his five contemporary-Christian albums, “I Put Away My Idols,” earned him a Grammy nomination.

Then, like so many other restless Protestants before and since, he began noticing the unintended consequences of the doctrine that, more than any other, animates the evangelical soul, “sola scriptura” (“by scripture alone”): namely, that in making every believer a one-man magisterium, it inevitably leads to an exponentially multiplying number of denominations and the absence of a unifying spiritual authority.

By the time that Dion, a cradle Catholic, happened upon an episode of Marcus Grodi’s EWTN program “The Journey Home,” he was, so to speak, ripe for the picking.

He returned to the Church in 1997, and he hasn’t looked back. Indeed, he has burrowed deeply into his Faith’s theological roots.

One fruit of these investigations has been his ability to give articulate reasons for the hope that is within him. Google any video of him giving his testimony, and were it not for his trademark beret and Bronx-inflected speech, you’d almost think that you were listening to a seminary-trained apologist instead of one of the last living survivors of the ill-fated Winter Dance Party tour.

Another fruit is “The Thunderer,” a “Son of Skip James” album cut that, as of this writing, is the only blues song to have been inspired by St. Jerome.

“[M]y definition of the blues,” Dion once told NPR’s Linda Wertheimer, “is the naked cry of the human heart longing to be in union with God.” The blues, he went on to say, are “a bit of salvation” because they let out emotions that if pent up would “spiral inward” and eat us alive.

Or, as Dion’s old friend Bob Dylan puts the matter in “Blues with Friend’s” liner notes, “You have to be careful with the blues. They’re strong with lust and you can overpay for them, but they quote the law.

“It’s a shame,” Dylan concludes, “more people don’t follow that law.”

As “Blues with Friends” makes unmistakably clear, Dion agrees with every word.