In 1994, I visited the Holy Land with a tour connected to Providence College. One of the stops was the port city of Jaffa. It is not one of the area’s most common tourist sites, despite being mentioned in Maccabees and in the Acts of the Apostles, which recount that St. Peter lived there for a time.

While there, one of the young coeds wanted to pick up a souvenir, and since no one else was interested, I accompanied her to a little store. We were the only customers, and it seemed that the proprietor was staring at us. I thought he was admiring the student, but he wanted to talk to me.

Eventually, in broken English, he asked if I was a Catholic priest. He was originally from France and it turned out that a French priest had saved him from death by hiding him and others in a basement. He could not recall the priest’s name, but he said he would never forget what he had done for him. Neither do I recall the man’s name, but I haven’t forgotten him. It was a grace so unexpected it seemed accidental.

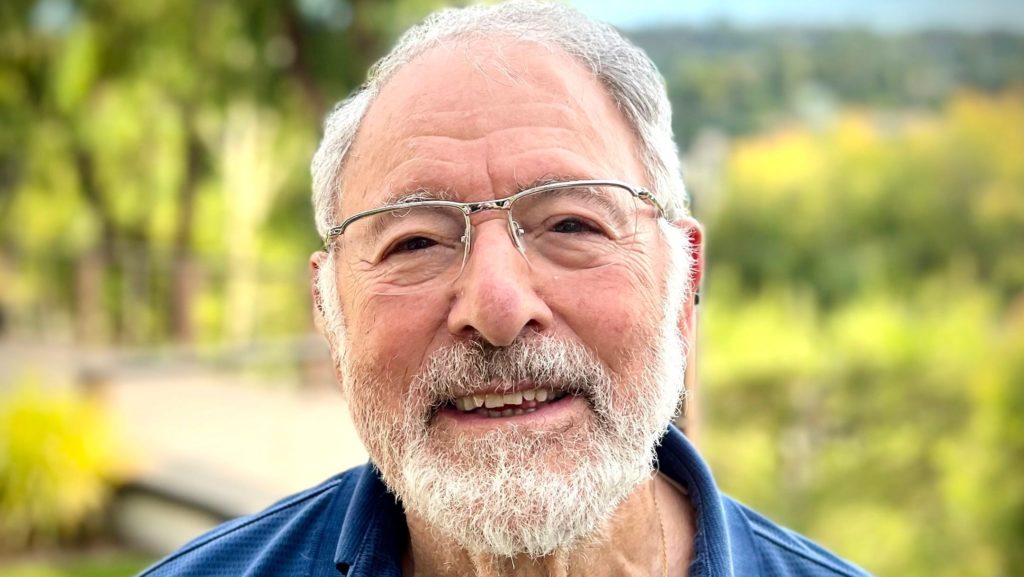

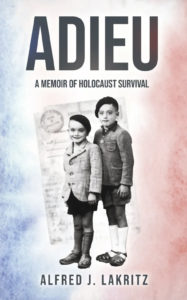

I have been thinking about that encounter lately, since reading “Adieu,” a memoir by Alfred Lakritz, a lawyer in Southern California whose father died in the Majdanek concentration camp in Poland after being arrested in France and moved several times around Europe (one of his stops was Drancy, outside of Parish, where the Jewish-Catholic poet Max Jacob died). The rest of the family managed to escape and eventually settle in California.

The book recounts the vicissitudes of the family, especially of the mother and his brother. It is carefully, at times very movingly, written and dedicated to his parents and to all who helped his family escape the Nazi Holocaust. Those included a community of nuns in Lourdes, who had an “orphanage” that was really a shelter for Jewish children. Lakritz considers it “miraculous”' that he, his mother, and his brother survived. For me, it was another example of Our Lady of Lourdes’s power to work miracles.

The period covered by the heart of the book was when the author was between 8 and 10. I think that should be considered in understanding some of Lakritz’s memories. For example, he recounts that peasants in southern France were taught by the priests that matzo bread was made with the blood of human victims. (I am sure he heard that ancient and terrible lie, but I doubt it was from priests.) There are hints of ambivalence in his attitude toward the Church, even though he speaks warmly of a priest in Lourdes and of the nuns who protected him. I also doubt that he was told to receive Communion at Mass, which he said he refused to do.

Like so many of us, Lakritz has some contradictory thoughts. He remembers the boys at the orphanage playing in snowball fights with the German soldiers, but in another passage writes that he was (and still is) disgusted because many of the soldiers attended Mass on Sunday. He calls them “hypocrites, murderers, pigs.”

His take on them is, “They were murderers.” I am not so sure. Those soldiers, like many in the Nazi military, may have been forcibly recruited and many probably were praying just to survive the war. They might not have known that the boys they engaged in snowball fights were Jewish, but they indicated something of their own boyishness in playing games.

Could these common soldiers ever be forgiven? “If they were entitled to such forgiveness,” Lakritz writes, “what was the Catholic Church and its clerics, bishops, cardinals, and the Pope doing for their victims?”

The myth of the all-powerful Catholic Church survives despite all evidence to the contrary. In what country of Europe was the Church politically strong? In Fascist Italy? In Nazi Germany, whose ideology was frankly anti-Catholic, as he admits, saying that crucifixes were taken down and replaced with swastikas? What exactly could the pope do that would not have provoked wholesale persecution from the German regime? The pope did things quietly, saving lives that he could. He lived in Axis territory, with the Gestapo at his gates for almost a year during the German occupation of Rome.

Years later, Lakritz reached out to the Archdiocese of Los Angeles in order to ascertain which group of religious had saved him and his brother. Sister Mary Jean Meier, a Mercy Sister who was the director of the archdiocese’s Office of Special Services, did a great deal of research and found out that they were sisters of St. Bernadette’s community based in Nevers, France. Lakritz arranged a meeting with the superior of the community to thank her, “for everything that was done for me — how the nuns hid me from the German military, fed me, clothed me, and showed me love and compassion.”

Nevertheless, he told Sister Mary back in LA that he “was angry with Pope Pius XII that he didn’t do anything for the Jews, and that many Catholics colluded with the Nazis and the Church described the Jews as Christ killers.”

Lakritz says Sister Mary listened in silence and then said, “You must never forget, but you must also forgive.” This is one of the themes of the greatest of memoirs about the darkness of the genocide, finding transcendent goodness in life and in people, “in spite of everything,” as Anne Frank wrote in her diary.

Reading “Adieu” made me pick up a book published in the 1950s, “Why I Became A Catholic” by Eugenio Zolli. He was a tremendous Jewish scholar and the Chief Rabbi of Rome. When the Allies liberated Rome, he became a Catholic.

It would be hard to imagine two books by European Jewish Holocaust survivors more different than these two. But I see a resemblance between the two men; both Jews who left Poland for the broader world; both passionately identified with their heritage; both extremely attached to their mothers who were “saints”; both very sensitive; both honest about their faults.

I think that both men could say what the rabbi said of himself, that he was better at loving than of making himself loved. Lakritz was intense from childhood. He still regrets his grandfather’s laughing at his new suspenders when he was 4 years old.

Both books are worth reading. Lakritz is much easier than the theological and mystical broodings of the unusual Christian rabbi, who never forgot his love for the book “The Zohar,” the Kabbalistic book. But both are windows to another world and an inspiration to faith. Both deal with the miracles of God’s providence.