In this season of waiting, I think of Samuel Beckett’s “Waiting for Godot,” the Chinese novelist Ha Jin’s “Waiting,” and T. S. Eliot’s “Wait Without Hope”: “I said to my soul, be still and wait without hope, for hope would be hope for the wrong thing. …”

We wait for the results of the biopsy, the door to open, the phone to ring, for the sun to come up, the curtain to rise, the check to clear, the flowers to bloom, the egg to hatch, for the pain to stop, for Christmas eve, to fall asleep.

One thing we don’t wait for — can’t “wait” for — is to wake up. Maybe in his mercy God gave us sleep because without a seven- to eight-hour break every day from the tension of perpetual waiting, we’d break down. Maybe he needs us to get out of the way for at least a third of the time, with our fear and fretting and scheming and “work,” so he can give us what we need for free.

As Psalm 127 has it:

“In vain is your earlier rising,

your going later to rest,

you who toil for the bread you eat;

when he pours gifts on his beloved while they slumber.”

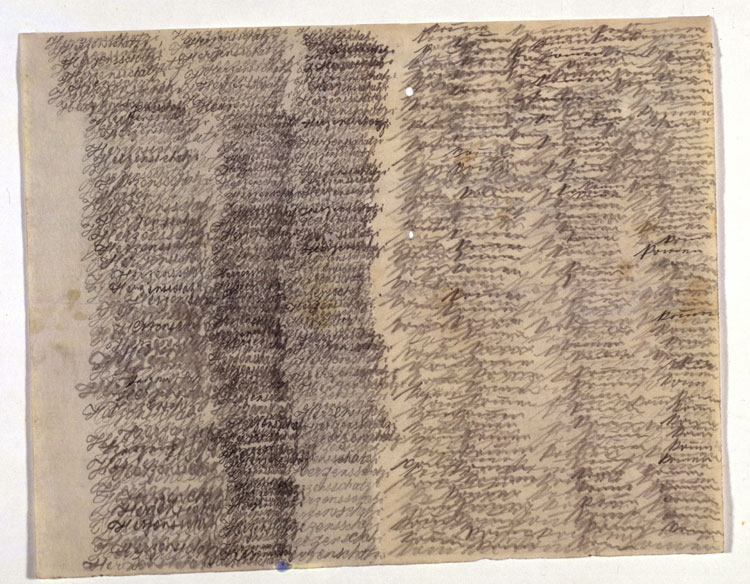

I once saw an exhibit of artwork from the early 1900s by patients at a German insane asylum. One framed piece consisted of a sheet of cheap paper on which was written in pencil the same phrase over and over and over, from left to right, and from top to bottom: line after line after overlapping line.

The artist, it turned out, was a woman in her 30s named Emma Hauck who had been diagnosed with terminal dementia praecox (schizophrenia). She was writing to her husband Mark: “Sweetheart Come,” the placard read.

The borne-down-upon pencil, the obsessive-compulsive copying out, the anguished plea to the universe — it was as if her entire being had become concentrated in that one impastoed prayer that looked like receding waves, or ripples on a shore.

She had to have written “Sweetheart Come” tens of thousands of times, and you were left to wonder whether Mark ever did come, knowing that, even if so, he probably didn’t come nearly often enough, or for a long, long time.

During Advent, I’m thinking as well of Father Luigi Giussani, founder of the Catholic lay movement Communion and Liberation (CL), who in 1953 played a Beethoven concerto for a group of students, one of whom, a woman named Milene de Gioia, fell into uncontrollable weeping, and for whom he then proceeded to search for the next 42 years.

“You can see well the difference between one soul and another, one sensibility and another, between one heart and another,” he told her that day. “Those others certainly wouldn’t have cried. Therefore, from that moment on, this piece became more meaningful for me. The longing that the fundamental theme generates, it’s such a longing, that for a sensibility like Milene’s, it made her burst into tears — this longing is man’s emblem of waiting for God.”

For 42 years, on every vacation, he asked his young followers to look for her in the phone books of all the regions of Italy, but in all that time he never found her. Until that day at the end of March 1996, which, as Guissani observed, “With Camus, we can call ‘the beautiful day,’ ” when his ex-student Milene was tracked down and invited to a CL gathering.

“They went to get her at 7:30 and, when she entered the house, in the dense crowd there at the door, I had no problem recognizing her — she was just the same!”

Afterward, he told his followers, “Kids, for 42 years I’ve been waiting to see again a girl who I last saw when was she 16 years old! Forty-two years of searching! So, then, tell me please, if virginity is something that forgets women. Can you imagine a fact of this kind? No, you can’t imagine it.’

“And, in fact, what made it possible to wait 42 years was a simple thing, totally positive, like a gift from God! And then, something absolutely gratuitous happens, totally gratuitous, that is, with no kind of self-serving calculation. Forty-two years! Tell me please if this isn’t a fairy tale!”

That March evening was a landmark event for Milene, too. “As soon as I arrived, everyone welcomed me exuberantly. I felt like the prodigal son returning home after many years. … I’ve never forgotten to confide in him, no matter what the circumstance, and I’ve come to understand that he is the one who orders every circumstance.”

With December 25 fast approaching, what strikes me as sublime isn’t so much that after all that time Milene and Guissani were reunited as that all that time he kept searching. So whatever we might be waiting for, let’s not lose heart! Giussani again laid eyes on his “girl,” and she on him. I insist on believing that Emma and Mark Hauck were similarly reunited in heaven.

And whether our own longing to be reunited with family and loved ones comes to fruition this year or not, Advent assures us that — somehow, sometime — Christ will come again.

Heather King is a blogger, speaker and the author of several books. For more, visit heather-king.com.

SPECIAL OFFER! 44 issues of Angelus for just $9.95! Get the finest in Catholic journalism with first-rate analysis of the events and trends shaping the Church and the world, plus the practical advice from the world’s best spiritual writers on prayer and Catholic living, along with great features about Catholic life in Los Angeles. Subscribe now!