The first crisis of the Church took place when Christianity was not even two decades old. There had already been disagreements, and even controversies, but this crisis was an issue that got to the very heart of the definition of Christianity itself: Would membership in the Church require adherence to the laws of Judaism?

To answer the question, the apostles convened the first synod, or council, of the Church, in about A.D. 50 (Acts 15).

We know that as the Church spread and grew, the very unity of the Church was invested in the bishops. Whenever it was necessary, to oppose some heresy or meet some challenge, the bishops of a particular region would gather to sort out the problem and keep everyone on the same page. But the decisions of these local synods would only be binding on the region of the Church represented by the bishops at the meeting, and they would not be binding on the whole Church.

As it turned out, the practice of convening synods never became a regular pattern. Synods in the early Church were convened on an ad hoc basis, and always reactionary, in the sense that they were always responding to a crisis in the Church. They don’t necessarily overlap or function as continuations of the previous councils, so they should not be seen as a series of councils, per se.

For the most part, each synod is a stand-alone event — which means that as an arm of the magisterium, a synod is an exception to the rule, something that is done because it is necessary in the moment, but out of the ordinary. It is never meant to be an ongoing or regularly repeating source of authority (we have the regular magisterium for that).

The region of North Africa is an example of a place where they experimented with regularly scheduled synods. What they found is that meeting too often in councils led to a politicizing of the Church, including ongoing lobbying, in which metropolitan bishops could manipulate the voting by creating more dioceses in their areas, so that they could create more bishops, so that their area would have more voting power.

Later, in the East, even the famous St. Basil the Great gave in to the temptation to make his brother and friend bishops just so they could support him and his projects. In actual practice, synods of the early Church could be as uneventful as a routine office or parish meeting, or they could be full of drama, complete with shouting matches and fistfights.

As time went on, new crises resulted in new synods. In the second century, a controversy over how to calculate the date for Easter resulted in synods in Rome and in other cities. In the third century, a controversy over the sacrament of reconciliation resulted in synods in Rome and Carthage. In the fourth century, the question of clergy celibacy (among other things) resulted in a synod in Elvira, Spain, but because the Church was illegal and persecuted, and travel was difficult. And being regional synods, their decisions were technically only binding on that region (although the synods of Rome would come to have more weight, since the bishop of Rome, the pope, ratified their decisions).

When the emperor Constantine legalized Christianity, he also gave Christian bishops the right to use the Roman transit system, which was until this time reserved for government officials (those government officials would soon complain that there were so many Christian bishops traveling to synods that they found it hard to get a seat in the wagon!).

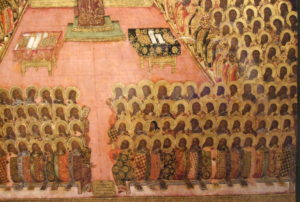

The first synod attended by the emperor was the Synod of Arles in A.D. 314. But this, too, was a regional synod, and it quickly became clear to everyone that what was really needed to face the current crises (not least would be the heresy of Arianism), was a worldwide council — one where every bishop in the world was invited, and the decisions would be binding on the whole Church. This was the Council of Nicaea, in the year A.D. 325. It would come to be called the first “ecumenical” (or worldwide) council.

Incidentally, Nicaea was the last time (for a long time) that laypeople were invited. They became a distraction, in part by treating the living saints like rock stars (hermits came in from the desert for the council, people who had been tortured in the last round of persecutions showed up with their scars, and the famous St. Nicholas was there). After 325, councils would be limited to bishops and their assistants.

The Council of Nicaea clarified the doctrine of the Trinity in opposition to the Arian heresy, and wrote the first draft of the Nicene Creed. The Second Ecumenical Council, the Council of Constantinople in A.D. 381, added to the creed, especially in the paragraph about the Holy Spirit. This gave us (essentially) the Nicene Creed that we recite in Mass every week.

In the early centuries of the Church, sometimes a council was convened by an emperor, but not without the sanction of the pope, who would generally determine who chaired the council.

Sometimes the pope couldn’t attend, but he was always represented by a delegation from Rome. When the Rome delegation read Pope St. Leo’s statement at the Council of Chalcedon in A.D. 451, it was reported that the assembled bishops cheered, “Leo speaks for Peter!” That may be a bit of an exaggeration, but the point is that the voice of the pope carried great weight at a council, even when he was not physically there.

In fact, one of the times that people tried to convene a council without the sanction of the pope, and where the pope’s statement was rejected — this council was determined to be invalid, and is now referred to as “The Robber Synod” (A.D. 449).

So although the words “synod” and “council” are basically synonymous, we can make a distinction between regional synods or councils and a general (or ecumenical) council, which is universal — that is, every bishop in the worldwide Church is invited, and the canons (resolutions) will be binding on the whole Church. In actual practice, the pope has a kind of de facto line-item veto, even of the canons of the ecumenical councils. For example, popes rejected individual canons from the Councils of Constantinople and Chalcedon.

Historically, the impact of any council — especially an ecumenical council like Vatican II — can take generations to have its full effect on the Church. Having a general council too often, the Church seems to have learned, would create an overlapping effect where the full impact of one council had not been realized before another one was convened.

It is also true that the ecumenical councils of the early Church did significant work that could never be undone, or even improved upon. For example, they literally defined what Christianity is by clarifying the doctrine of the Trinity and orthodox christology in opposition to heresies. Their conclusions are treated as being as authoritative as Scripture, because they were defining the authoritative interpretation of Scripture.

Once the Church faced permanent schism, the concept of an ecumenical council is a matter of point of view — what we as Catholics call ecumenical councils would not all be considered so by the Orthodox, and what we agree with the Orthodox are ecumenical councils would not all be accepted by the Oriental Orthodox, who split from the Church after the Council of Chalcedon. The point is that a council is not authoritative because it’s a general council — it is a general “augustcouncil” because it is authoritative, and that authority is determined by the approval of the pope and by its canons standing the test of time.

And so with regard to general councils, there is an aspect of them in which their work is done. Doctrines are defined as well as they ever will be. Christianity has been defined, and no one alive today or in the future can redefine (or reimagine) it. The historical fact of the debates, controversies, and crises do not at all diminish the authoritative teaching of the Church, in fact they confirm it, since the work of clarification has been done. From the beginning, and even when there were new situations to address, the role of a council was always to determine what clarification of belief, or what course of action, was most consistent with received tradition.

With regard to synods, or nongeneral councils, it is possible that new crises can create the need for new synods. But unless a council is declared to be a general council, its decisions could only be binding on the whole Church if the pope were to ratify them as such, which would amount to a new infallible pronouncement, “ex cathedra.”

If future synods are to be faithful to their historical counterparts, they would be convened in the recognition that they are an extraordinary measure meant to deal with a certain crisis, which may be new, but that their task is to determine the resolution of the crisis that is most consistent with the faith handed down from the apostles.