Catholics in Mexico have condemned an initiative to legalize euthanasia, accusing lawmakers of simply wanting to "save money," while presenting their proposal "under the guise of false piety."

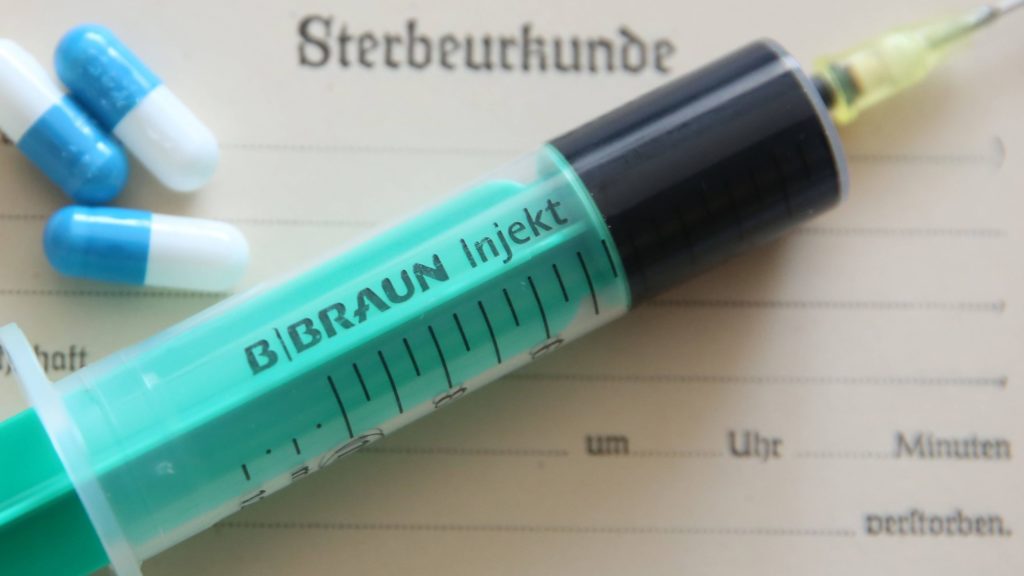

A proposed law presented in the lower house of Congress is expected to be debated by its health commission and proposes allowing euthanasia for certain patients -- including those with irreversible medical conditions that cause chronic pain -- so long as they receive medical and psychological evaluations and their written request is reviewed by a notary.

The Mexican bishops' conference released a statement, dated Nov. 27, opposing the initiative, saying that "more than an act of compassion, taking the life of another person is a gesture of abandonment, which is why euthanasia is always an attack against the dignity of the person."

The document, signed by Bishop Jesús José Herrera Quiñónez of Culiacán, director of the bishops' ministry for life matters, continued, "The mere possibility of euthanasia already eliminates all hope, and without it, human beings lose the meaning of life. The key is to understand the difference between 'causing death' (killing) and 'allowing death' (accepting its natural end)."

The Congress's health commission had planned to discuss euthanasia Nov. 28, but canceled without explanation, Mexican media reported.

Four parties in the lower house -- including the ruling MORENA party, which holds a majority with its allies -- proposed reforms to the General Health Law, which would allow euthanasia in certain circumstances. Those circumstances include terminal illness, irreversible conditions and "being in agony."

The proposal defined euthanasia as "the deliberate act of ending the life of a patient suffering from a terminal illness or irreversible medical condition, at the express and voluntary request of said patient." It also requires patients to receive full medical and psychological evaluations.

It proposes to abolish Article 166 BIS 21, which prohibits the use of euthanasia in the country.

The proposal sparked disquiet among church leaders and pro-life groups in Mexico, which recalled that the lower house hosted "National Euthanasia Week" in June 2022. "The regulation of euthanasia in Mexico, if approved by the legislative branch, could mean, in terms of investment in health, a 'savings' for the state," Emmanuel Reyes Carmona, the health commission's president, said at the event.

Recalling these remarks, an editorial by the Archdiocese of Mexico City's publication Desde la Fe said Nov. 25, "Under the guise of false piety, they seek to hasten the death of terminally ill people in Mexico."

"In this 'euthanasia week' the objective of this practice was publicly exposed: to save money," it continued.

During the 2022 event, it was mentioned that palliative care was costly and that properly regulated euthanasia "could alleviate" the costs of such care.

"Given this statement, it can be clearly concluded that the public health system would prioritize the application of euthanasia, rather than palliative care, leaving these services, which many families will surely seek for their loved ones, in a private health system," Desde la Fe's editorial continued. "In short, palliative care for those who can pay for it, euthanasia for those who cannot."

President Andrés Manuel López Obrador has promised to create a health system on par with Nordic countries by the time he leaves office in 2024. But his administration hasn't invested substantially in health, according to analysts, even during the COVID pandemic.

"All five Nordic countries have welfare state models with tax-funded health care systems and minor private health care sectors," according to research by the National Library of Medicine in the U.S.

An analysis by the National Council of Social Development Policy Evaluation, which publishes a multifactorial measure of poverty in Mexico, found 39% of Mexicans -- about 50.4 million people -- lacked access to health services in 2022, up from the 16% of the population lacking access when López Obrador took power in 2018.

As of 2023, euthanasia and/or assisted suicide is legal in Belgium, Canada, Colombia, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Portugal (where it is awaiting regulation), Spain and all six states of Australia. In the United States, assisted suicide is legal in 10 states and the District of Columbia.

In his Nov. 27 statement on the proposed legislative reforms regarding euthanasia, Bishop Herrera asked decision-makers, people of goodwill and the church in Mexico to direct their efforts "to put in place palliative means to address (patients') pain without ever opening the door to actions that directly take the life of a human being, whether he or she asks for it or not."

"Let us not lose our humanity with actions that dehumanize us," he concluded before praying for the intercession of the Virgin of Guadalupe to encourage all to treat all those who suffer with love, attention and care.