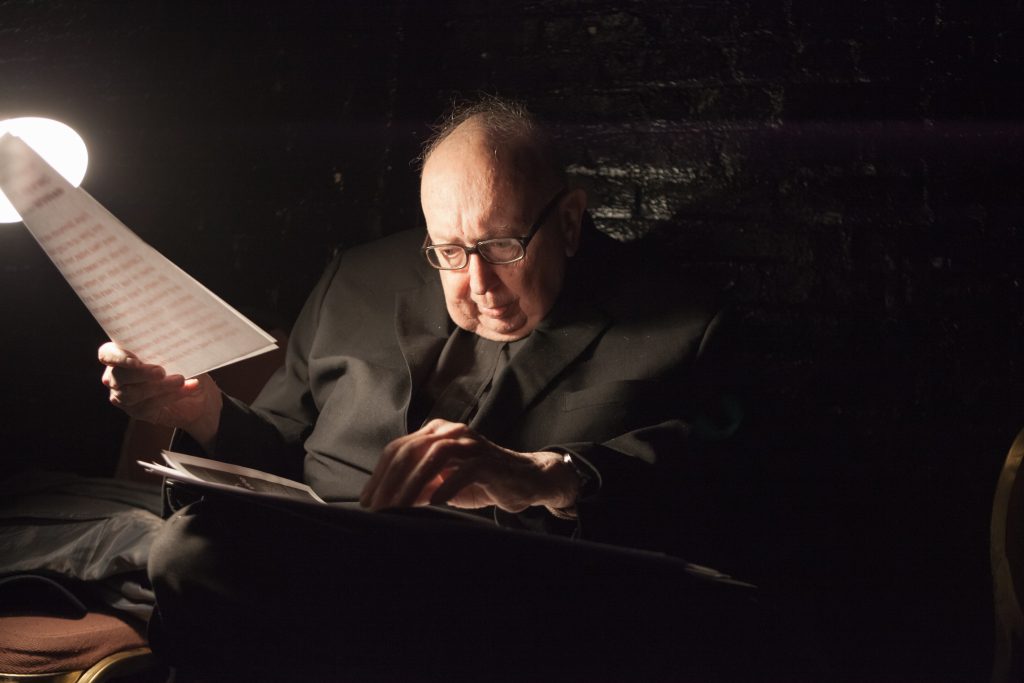

Msgr. Lorenzo Albacete (1941-2014) was born in San Juan, Puerto Rico, majored in physics and aerospace science at The Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C., and was engaged to be married when “the call” came.

He was ordained in 1973 at the age of 32, became an assistant to the archbishop of Washington, and over time became close friends with both St. Pope John Paul II and Pope Benedict XVI.

Notoriously rumpled, perpetually late, a negligent returner of phone calls and emails, he chain-smoked, loved food, drink, and good conversation, and had a wicked sense of humor.

Author Michael Sean Winters tells the story of how Albacete, his beloved brother Manuel, and a third guest once came to a Washington, D.C., restaurant at which Winters was a server during the Triduum. “When all three of them ordered lamb chops, I interjected. ‘You can’t have lamb chops — it’s Good Friday.’ Without missing a beat, Lorenzo said, ‘Oh, Mike, [he was the only person who ever called me “Mike”], we had an ancestor who died fighting in the Crusades and have a dispensation in perpetuity.’ ”

But Msgr. Albacete was anything but superficial. In “God at the Ritz: Attraction to Infinity” (Crossroad, $13.48), a collection of essays about religion, politics, and sex, he posited: “The inhabitants of the world of suffering are the ones who truly transform the world. They are the true revolutionaries on behalf of human dignity. … It is necessary to suffer so that the truth not be crystallized in doctrine, but be born from the flesh.”

He appeared on Charlie Rose and Frontline, wrote for The New York Times, and publicly debated acerbic atheist Christopher Hitchens. In his later years, he helped establish a New York-based educational arm of the lay Catholic organization Communion and Liberation.

He died at 73 of complications of Parkinson’s disease.

“The Relevance of the Stars: Christ, Culture, Destiny” (Slant, $19), a posthumous essay collection edited by Lisa Lickona and Gregory Wolfe, emerges from Msgr. Albacete’s spiritual transformation in the early 1990s. It was then that he met an Italian priest from Milan: Father Luigi Giussani (1922-2005).

“What Giussani proposed,” the editors observe, “was a return to the central experience of Christianity, God’s own method, summed up in the encounters that people have with Christ in the Gospels — John and Andrew, Zacchaeus, Mary Magdalene, the woman at the well. Jesus did not convince these men and women by discourse, but rather won them over through the power of his person, his gaze, his gestures, his presence.”

Msgr. Albacete’s intellect ranged wide, and if he sometimes posed questions, meandered around to other questions, and never quite got back to the first, so be it: Reading him I found myself, again and again, nearly shouting “Yes!”

The first chapter, “The Lovers and the Stars,” considers the faith versus reason question.

“This is the proposal,” he avers. “It’s where faith (the stars) enters in and broadens, purifies. Here it is proposed that what we call faith above all is the healing of our humanity. What we suffer from, whatever its origin, we must overcome this wound, this disaster, this separation of reason from affectivity.”

From “Overcoming Dualism”: “In practical terms this means that everything human that is interesting can lead me to Christ.”

From “The Church of the Infinitely Fractured”: “[W]hat saves us are the facts of the life of Christ and of his death and resurrection, not the ethical consequences drawn from them from the right wing or the left wing.”

In “Searching for Truth Together,” he observes that, for the early monks, “The logos is not at all merely an intellectual concept, but a reality that catches our attention, that is addressed to us. It is what Giussani would call an encounter. It is a call; it is therefore a vocation. Human life itself was experienced as a response to a word addressed in human words; life became a response to this encounter with the Word.”

Msgr. Albacete anticipated and addressed “critical theory,” the godless, rigidly enforced ideology that holds increasing sway in the fields of politics, media, education, and even art.

The chapter “Learning to Say ‘I’ ” considers the tension between identity (modern) and individuality (ancient). “The human heart is made, structured, or given as a yearning for a mystery that man is unable to reach. … This is my proposal: the modern problem of individuality versus an identity defined by belonging is the result of modernity’s fear of the possibility of the Incarnation.”

From “The Mystery and the Holocaust”: “The contemporary disdain for the capacity of human reason abandons the religious sense to the irrational, thus paving the way for the worship of those idols of racial, ethnic, or national identity which led to the Holocaust and the other barbarous planned and systematic horrors so characteristic of our time.”

“Religion is welcomed only when it is reduced to harmless sentimentality or a socially convenient disposition to self-control. What makes us afraid is the claim of the presence in the world of the infinite mystery for which the heart desires.”

But treat yourself to the book and read these profoundly human, intelligent, and thought-provoking essays for yourself. As the editors point out, Msgr. Albacete is an “astronomer of the spirit.”