ROME — Theologically, of course, all bishops are equal, all fully successors of the apostles and sharing the same dignity. For a variety of political and ecclesiastical reasons, however, some bishops are quite obviously more equal than others.

It’s a safe bet, for example, that Pope Francis and his Vatican team spent just a bit more time contemplating the choice of a new prelate in Hong Kong, currently at the center of a superpower tug of war, than they did a new auxiliary bishop in Houston, two nominations announced within a span of 24 hours in mid-May.

The appointment of Father Stephen Chow, SJ, for the former British territory in China has been interpreted by longtime China-watchers as an attempt to strike a delicate balance between hardline anti-Communist clergy who reject dialogue with Beijing, and clerics overly subservient to the Chinese government and thus unwilling to defend religious freedom and the rights of the Church.

The post had been vacant for almost four years, since Cardinal John Tong Hon retired at the age of 78. The fact it took so long to name a successor underscores the deep sensitivity of the assignment.

In the case of Hong Kong, the difficulty of the gig is mostly about geopolitics. In other cases, a bishop’s job takes on special intensity because of internal ecclesiastical factors: While being the archbishop of Boston probably never has been a walk in the park, think about what awaited then-Bishop Sean O’Malley in 2003 in the wake of the explosion of the sexual abuse crisis and the spectacular fall from grace of Cardinal Bernard Law.

With that in mind, here’s a rundown of arguably the three hardest bishops’ assignments in the world that are currently vacant and waiting to be filled. It’s not that these are, in absolute, the toughest places on the planet to be a bishop, simply that right now, they’re the biggest sources of heartburn awaiting a new leader.

Each is the sort of gig for which a broad swath of Catholic clergy probably would find themselves praying that this cup may pass.

Minsk, Belarus

Vacant since: January 2021

Former occupant: Archbishop Tadeusz Kondrusiewicz (retired)

Last Friday, the U.S. government announced a series of sanctions against Belarus following the forced landing of a Ryanair jet and the arrest of opposition journalist Roman Protasevich. It was merely the latest effort by pro-Russian President Alexander Lukashenko to crack down on dissent and free speech, after massive and sometimes violent pro-democracy protests in the wake of a disputed election last November.

Archbishop Kondrusiewicz inadvertently became part of the drama last year when he spent several months in exile after being refused reentry into Belarus by Lukashenko, who was upset with public statements in which he archbishop appeared to express sympathy with the protesters.

The archbishop was allowed back into Belarus on Dec. 24, in time to lead Christmas celebrations, but his resignation was accepted by Pope Francis just days later, in what many observers interpreted as a quid-pro-quo deal with the Lukashenko regime.

Not only does the archbishop of Minsk have to navigate life in a de facto police state, but he’s also on the front lines of the ever-complicated ecumenical relationship with the Russian Orthodox. Although relatively few Belarusians are religiously practicing after decades of state-imposed atheism, Russian Orthodoxy remains the largest denomination and a symbol of national identity.

The Vatican has long prioritized détente with the Orthodox, but relations with Moscow remain fraught because of historical resentments of Rome as well as the role of the Russian state in Church affairs.

In other words, the Archdiocese of Minsk has “headache” written all over it. Probably the only guy who ever thought it represented a break was Archbishop Kondrusiewicz … whose previous gig was the archbishop of Moscow.

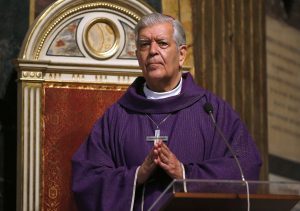

Caracas, Venezuela

Vacant since: July 9, 2018

Former occupant: Cardinal Jorge Urosa Savino

On the subject of hostile regimes, one need look no further than Venezuela, where the relationship between the Catholic hierarchy and the government of Nicolas Maduro, the socialist leader who replaced Hugo Chavez after his death in 2013, has been strained for a long time.

Many bishops have accused Maduro publicly of being dictatorial, abusing power, and wrongfully incarcerating the political opposition, and Maduro and allied groups have found ways to make their displeasure known.

Venezuela, of course, like virtually all of Latin America, is a traditionally Catholic nation, which means the role of the Church in political and social affairs is always crucially important. At least openly, the Vatican has mostly stayed on the sidelines of the church/state battles, urging diplomacy and dialogue.

According to the UN Refugees Agency, an estimated 5.4 million people have fled Venezuela since 2013, in what has long been considered the worst migration crisis in the world not resulting from war. The country features the world’s highest inflation rate, medical shortages, and constant energy cuts due to lack of infrastructure.

Maduro at the moment is seeking to court the Biden administration in an effort to ease U.S. sanctions, and in 2019 Maduro asked the Vatican to help mediate Venezuela’s internal conflicts. At the time, Pope Francis replied by saying that previous agreements for dialogue efforts had not been respected.

In late April, Italian Cardinal Pietro Parolin, currently the pope’s top diplomat and a former papal ambassador in Venezuela from 2009 to 2013, canceled a trip to the country at the last minute, citing COVID-19 concerns.

In sum, the next archbishop of Caracas will face a government with a chip on its shoulder vis-à-vis the Church, a pope who perhaps wants the new man to persuade his fellow bishops to cool it a bit, and a cardinal-secretary of state constantly looking over his shoulder because of his own experience on the ground in the country.

Interested, anyone?

Ahiara, Nigeria

Vacant since: February 2018

Former occupant: Bishop Peter Ebere Okpaleke

Here’s a case in which the problems aren’t geopolitical or diplomatic, but have to do with internal ecclesiastical dynamics, but that doesn’t make the problems any less gigantic, because the small Diocese of Ahiara is, arguably, the single most impossible place in the world right now to be a Catholic bishop.

Ahiara became vacant in September 2010 when Bishop Victor Adibe Chikwe died at the age of 72. Two years later a successor was named in Bishop Peter Okpaleke, who hailed from another part of Nigeria, and from that point forward the situation quickly became toxic.

Members of the majority Mbaise ethno-cultural group in Ahiara refused to accept Bishop Okpaleke, insisting they wanted a bishop from their own group and chosen from the local clergy. Otherwise, they argued, the Vatican was practicing racial discrimination by favoring one ethnicity over another. Bishop Okpaleke had to be ordained outside the diocese and, in the end, never took possession of it.

In June 2017, Pope Francis demanded that all priests of Ahiara write him within 30 days pledging their obedience to his authority, including accepting Bishop Okpaleke as their shepherd. While letters of apology apparently were sent, the priests and laity in Ahiara never backed down, and eventually Bishop Okpaleke resigned and was given another diocese.

So, now, imagine the situation awaiting whoever’s up next. If the new bishop is Mbaise, he’ll forever be seen as the guy who got the job simply because he was the right ethnicity — and, further, he’d have to prove that he can be the shepherd for the diocese’s minorities, too. If he’s not, and assuming he could even somehow manage to take charge, his term will be forever bedeviled by the resentments of a large swath of his flock.

Again, anyone interested?