Unless the Ukrainian army’s current counteroffensive ends in clearcut victory for either Ukraine or Russia — an outcome that seems unlikely at the moment — it is possible, though hardly certain, that conditions then will finally exist for a cease-fire and peace talks leading to the war’s conclusion. Since the counteroffensive presumably will continue for another two or three months, that raises the possibility of serious developments as early as this fall.

But while early talks are not certain, something else is: There will be no talks and no peace until each side is convinced it has nothing to gain from further fighting.

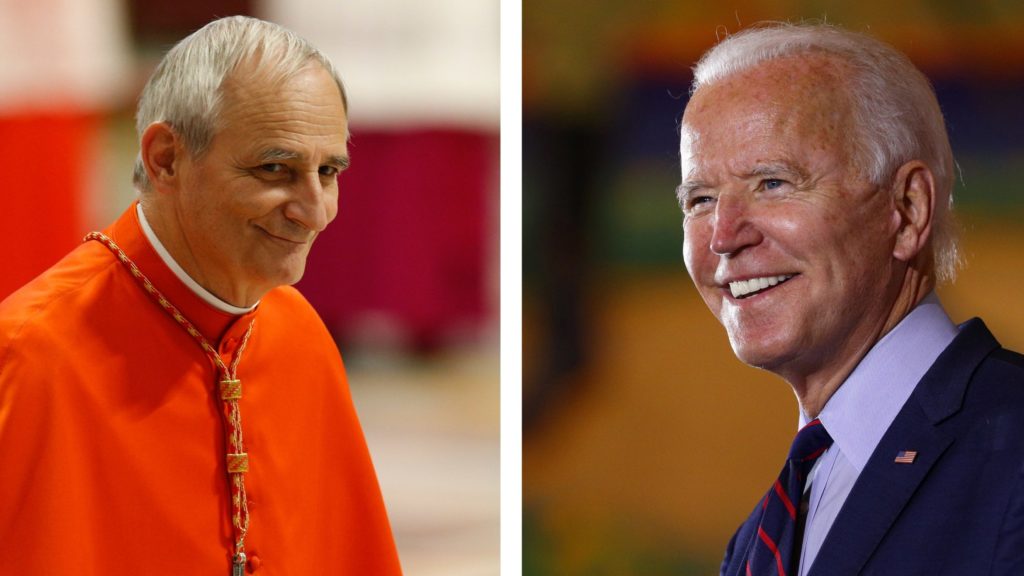

Meanwhile, there has been a flurry of Vatican diplomatic activity on behalf of peace. That was the backdrop for last month’s White House meeting between President Biden and Pope Francis’ special envoy Cardinal Matteo Zuppi of Bologna, president of the Italian bishops’ conference.

Cardinal Zuppi met earlier with government and religious officials in Russia and Ukraine, and, the Vatican has announced, will next meet with Chinese government officials in Beijing.

According to Cardinal-designate Christophe Pierre, the papal nuncio in the U.S., who was also at the two-hour meeting with Biden, Zuppi spoke about securing the return to Ukraine of children who’ve been deported to Russia during the war. He also delivered a letter to the president from Francis that presumably repeated the pope’s willingness to help mediate a settlement.

In New York the same day, the Holy See’s permanent observer to the United Nations, Archbishop Gabriele Caccia, presented a statement to the U.N. General Assembly that quoted Francis urging use of all diplomatic means, “even those that may not have been used so far,” to end the war and calling specifically for a cease-fire and peace talks. Zuppi presumably made the same point in his meeting with Biden.

As to what a settlement might look like, the general lines are clear. Each side would remain where it is when the shooting stops. The cease-fire would be followed by U.N.-supervised voting in which the people of disputed territories could say whether they wanted to be part of Ukraine or Russia. Establishment of an agreed-upon frontier supervised by a U.N. peacekeeping force would follow, along with security guarantees (to which the U.S. would be a party) to ensure each side had nothing to fear from the other.

Sketching the terms is easy, but actually getting an agreement will be a daunting task made more difficult by mutually reciprocated enmity and distrust between the Ukrainians and the Russians after months of barbaric violence. Given that reality, the services of an honest broker such as the Holy See could help a lot.

Zuppi’s meeting with President Biden was recognition that the U.S., as Ukraine’s principal military and political backer, is a party to the conflict. And the rationale for Biden to put more muscle into the search for peace lies in the rise of isolationism in segments of the population eager for an end to American involvement in this foreign adventure. Better than anyone, Biden surely grasps that if the fighting persists into the new year, presidential candidates of both parties, capitalizing on neo-isolationist sentiment, will press him to support a settlement in Ukraine on the best terms available.

In short, the American government will be increasingly unlikely to sit by quietly and confine itself to merely wishing the Ukrainians would see the desirability of seeking peace even though some of their stated goals in the war remain unmet, as may well be the case.