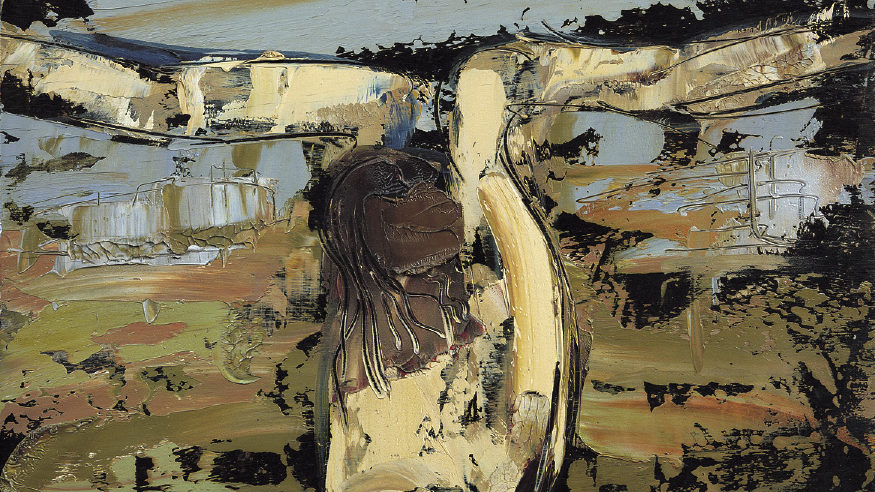

“I paint on black because painting is not representing a light that is and that’s all, but rather participating in the light that is becoming out of the darkness.”

— William Congdon

“The Sabbath of History: William Congdon, with Meditations on Holy Week,” by Joseph Ratzinger (Knights of Columbus Museum, $45), is a catalog on the work and reflections of painter William Congdon (1912-1998).

Congdon, an abstract expressionist and a convert, came to see the crucifix as his one — as the — subject. In 1961, he observed: “Our every experience finds its apex, its substance, and ultimate meaning in the death and Resurrection of Christ, whose image is the Cross (instinct crossed by the spirit). For this reason, every subject that takes me to paint sooner or later reveals, better still becomes the Cross of Christ. … Now, without looking for inspiration elsewhere, I always paint the Crucifix, because in it lies everything I have seen and lived so far until I have painted, and everything I shall ever see in the future; sum of yesterday and prophet of tomorrow: death and Resurrection.”

The catalog (available for free at Internet Archive) was compiled to accompany a 1998 exhibition of Congdon’s paintings at the Knights of Columbus Museum (now the Blessed Michael McGivney Pilgrimage Center) in New Haven, Connecticut.

The museum paired Congdon’s paintings with new English translations of Father Ratzinger’s meditations on Holy Week and reflections on the “Origins of My Meditations on Holy Week” in such a way as to bring hope “especially near in the hour of silence and darkness” surrounding the crucifixion.

Congdon and Father Ratzinger never met, but the paintings and meditations beautifully complement each other.

Of the Crucifixion and Resurrection, Father Ratzinger wrote: “The image [the disciples] had formed of God, into which they tried to force him, had to be destroyed so that they could see heaven above the rubble of the destroyed house, so that they could see him who always remains infinitely greater. We needed the darkness of God, the silence of God.”

Born and raised by a wealthy family in Rhode Island, Congdon studied English literature at Yale, worked for a year during World War II as a volunteer ambulance driver, and in 1948 moved to a cold-water flat in the Bowery.

“This was the first time I was alone and solely responsible for my life, which now I began to create in my first paintings,” he later wrote.

His first show, at the prestigious Betty Parsons Gallery in 1949, included some of the many drawings he had made during the war, among them of the liberation of the Nazi death camp at Bergen-Belsen.

As for the paintings — thickly impastoed urban landscapes often incised by awls — Congdon wrote: “Black abstraction of the city on lead. The sun is usually chartreuse and violet (or orange).’

He was anointed “A Remarkable New U.S. Painter” by Life magazine in 1951.

While continuing to show in New York, he moved to Venice.

His paintings lightened, became gilded with luminous grays, touches of gold and pale green, the vibrant saffron of warming fires.

“The orange moon that had risen above my fear-ridden vision of New York,” he wrote, “became the golden basilica of S. Marco to which I had access.”

He also began to travel frequently. On his first trip to Assisi, in 1951, he was transfixed by the Byzantine crucifix in the convent of San Damiano before which St. Francis was said to have been praying when he received the commission to rebuild Christ’s church.

He converted to Catholicism in 1959, effectively committing professional suicide, and lived the next 20 years in Assisi and Subiaco, increasingly focused on the crucifix.

“The joy and the peace gained through daily Mass and Communion with Christ released me from tension,” Congdon noted. “His love, which transcended my own limited and carnal sentiments, led me to a freedom in which I was constantly renewed in body and in spirit.” As he journeyed in the ’70s to Calcutta, Dakar’s former slave ports, and other sites of extreme poverty and sickness, his paintings came to reflect “an inner state of physical and redemptive suffering.”

His portrayals of the Crucifixion had heretofore featured roughly recognizable T or Y shapes, the rough white figure of Christ slumped against a dark background.

Of his 1974 painting “Crocefisso No. 90” (Crucifix), Congdon wrote: “It is all flat squashed by lava flow, but trampled as if the traffic of ‘sin’ had crossed over it for or since all eternity, until the body, what was body, became a stain. It is the road of Bombay, it is the world that continually tramples Christ under. The tar of the road became Christ who became tar in order to let himself be flattened until he flowed in the fire of love, beyond any boundary. He flows everywhere, and even more in the splinters of the ashes like a bombardment of hate. It is everything: sin without limits. And yet, under and through the ‘flow,’ his shape remains, the image that redeems.”

The image that redeems; the image that keeps us at our post when Holy Week fades from memory and we, too, are tempted once again to trample Christ.

Congdon lived the last 20 years of his life in the Milanese countryside, his studio adjacent to a Benedictine monastery, and painted up to a few days before his death at 86.